The numbers are still daunting, if not staggering: four hundred and fifty novels and story collections in print. At one point, the unbelievable pace of a book a month. More than 1,400,000,000 books sold. Fifty films and 123 TV episodes. Translated into 55 languages. Published in 44 countries. The 16th most translated author in the history of the world. And, more salaciously, 10,000 women (largely prostitutes or, as he called them, “professionals”) bedded. At such quantities, all numbers are approximate. Perhaps more importantly, with such a prodigious output, critical response can be confused at best.

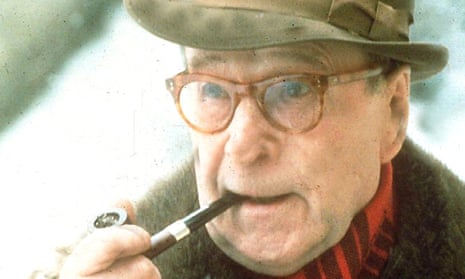

This is the overwhelming legacy of Georges Simenon (1903-1989), the Belgian creator of Jules Maigret, perhaps the best-known French detective in history. But lost in that forest of numbers is the fact that the fellow was of the greatest writers of the 20th century.

My purpose here, however, is not to celebrate the detective work. In my estimation, the quality of those books pales in comparison to that of the other, lesser-known segment of Simenon’s vast oeuvre - the romans dur or “tough” novels. I call them superior not merely because they break through the constraints of the genre (for one thing, when we read a series detective novel, we’re reasonably sure of how it’s going to end - the problem will be solved and the hero will live to solve another crime on another day), but because they deal with such a vast array of characters and situations and settings.

Simenon was the modern incarnation - or reincarnation - of Balzac (or, if you will, the anti-Proust) and despite his lifelong contention that he was only interested in the “little people,” he was equally at home penetrating the souls and psyches of characters as diverse as heads of state (The Premier), rogue sea captains (The Long Exile), and displaced Jewish shopkeepers (The Little Man From Archangel). And he was a master psychologist with little regard for political or social concerns; rather, he was infinitely more concerned with “mending the destinies” of his often-doomed protagonists.

This relentlessly downbeat canon (the one exception among his straight novels was The Little Saint, which was very loosely based on the life of Marc Chagall) may be one reason why Simenon’s work has never been wildly celebrated in the US, where, coincidentally, he lived for several years and, some critics argue, was at the very apex of his powers as writer. Or perhaps it was the fact that Americans typically like their novels fat, and Simenon’s rarely broke the 200-page mark. Or maybe it had to do with the often wooden translations of his work, remedied to a small extent recently by new versions brought out by the New York Review of Books.

But my own take is that this popularity deficit has to do more with the pronounced American trait not to look too deeply within and to flinch at what we find there. Simenon was unequalled at making us look inside, though the ability was masked by his brilliance at absorbing us obsessively in his stories. My own favourites are Monsieur Monde Vanishes, The Man On the Bench in the Barn, and The Train, among many others - most of them masterpieces of efficiency and nary a wasted word. Though in the case of this author, there are so many titles that it’s difficult to select just five or even 10.

I learned pretty much everything I know about writing from Georges Simenon. “Throw out all the literary stuff,” - adjectives, adverbs, sesquipedalian words and sentences - counselled Simenon’s mentor and editor, Colette. (What she actually told him was, “It’s nearly there, but not quite ... too literary. Don’t make literature. No literature, and it will work.” Good advice, in my opinion, for the unreadable meta-fictionists.)

Whenever I tire of trying to plough through the latest over-hyped current work of “genius” and put it down in mid-sentence, I rummage for an old Simenon.

I rarely go wrong.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion