Cornwall during the Iron Age and - Cornwall Archaeological Society

Cornwall during the Iron Age and - Cornwall Archaeological Society

Cornwall during the Iron Age and - Cornwall Archaeological Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY No. 25 (1986)<br />

50<br />

IRON AGE <strong>and</strong> ROMANO-BRITISH<br />

SITES<br />

5/0<br />

<strong>Cornwall</strong> <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Roman Period<br />

20<br />

HENRIETTA QUINNELL<br />

In later British prehistory change in <strong>the</strong> archaeological record is currently interpreted as<br />

<strong>the</strong> result of contact <strong>and</strong> exchange between contemporary communities. Detailed studies of<br />

cross-channel trade <strong>and</strong> of <strong>the</strong> development of boats show that frequent contact was feasible<br />

(eg Cunliffe, 1982). There may have been some migration on a small scale, but <strong>the</strong> idea that<br />

major invasions produced social <strong>and</strong> cultural change has been discredited. This is partly<br />

because so little material of continental origin has been found in Britain; partly, <strong>and</strong> more<br />

importantly, because underlying insular trends in farming, house construction <strong>and</strong> defence<br />

have been seen to have deep local roots, <strong>and</strong> differ substantially from practices along <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn littoral of Europe. Cunliffe's survey <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> Communities in Britain (1974 <strong>and</strong><br />

1978) explains <strong>the</strong>se trends <strong>and</strong> simplifies comparison of <strong>the</strong> Cornish evidence with that from<br />

<strong>the</strong> rest of Britain. He describes <strong>the</strong> British <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> in terms of regional tribal areas <strong>and</strong><br />

of chronologies which are increasingly based on radiocarbon dates. <strong>Cornwall</strong> comes under<br />

<strong>the</strong> broad tribal grouping of <strong>the</strong> Dumnonii (1978, 111) but <strong>the</strong> study shows how poorly <strong>the</strong><br />

Cornish archaeological record for this period is understood, compared to o<strong>the</strong>r areas of<br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn Britain. In particular, <strong>the</strong> range of radiocarbon dates from <strong>Cornwall</strong> is not yet<br />

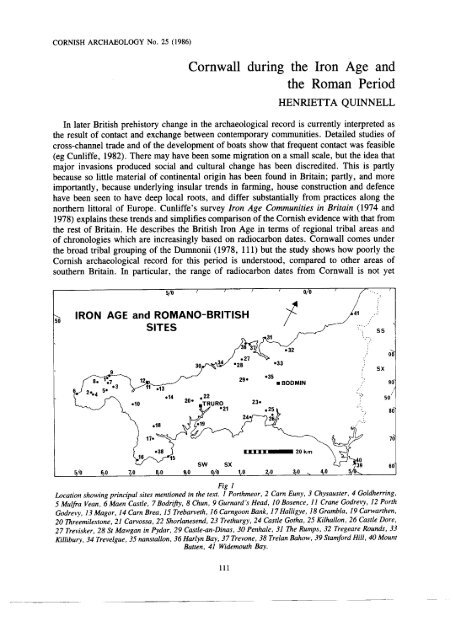

Fig 1<br />

Location showing principal sites mentioned in <strong>the</strong> text. 1 Porthmeor, 2 Cam n Euny, 3 Chysauster, 4 Goldherring,<br />

5 Mulfra Vean, 6 Maen Castle, 7 Bodrifty, 8 Chun, 9 Gurnard's Head, 10 Bosence, 11 Crane Godrevy, 12 Porth<br />

Godrevy, 13 Magor, 14 Cam Brea, 15 Trebarveth, 16 Carngoon Bank, 17 Halligye, 18 Grambla, 19 Carwar<strong>the</strong>n,<br />

20 Threemilestone, 21 Carvossa, 22 Shorlanesend, 23 Trethurgy, 24 Castle Gotha, 25 Kilhallon, 26 Castle Dore,<br />

27 Trevisker, 28 St Mawgan in Pydar, 29 Castle-an-Dinas, 30 Penhale, 31 The Rumps, 32 Tregeare Rounds, 33<br />

Killibury, 34 Trevelgue, 35 nanstallon, 36 Harlyn Bay, 37 Trevone, 38 Trelan Bahow, 39 Stamford Hill, 40 Mount<br />

Batten, 41 Widemouth Bay.<br />

111<br />

30<br />

40<br />

5

adequate for <strong>the</strong> establishment of a detailed local chronology, although those we have present<br />

a very different outline picture to that perceived 28 years ago, when Dudley (1958) wrote<br />

<strong>the</strong> previous review article. Sites not referenced in <strong>the</strong> present paper are detailed in that<br />

earlier review.<br />

The terminology employed to describe <strong>the</strong> Cornish <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> has altered considerably, <strong>and</strong><br />

confusingly. The former ABC system was based on <strong>the</strong> concept of invasions triggering<br />

archaeological change, A deriving from <strong>the</strong> continental Hallstatt <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, B from La Tem<br />

<strong>and</strong> C from Belgic groups, but this concept is no longer generally acceptable. In papers on<br />

Cornish material published up to around 1970 <strong>the</strong> ABC system was widely used, generally<br />

with a late chronology which radiocarbon dating now allows us to leng<strong>the</strong>n. As we cannot<br />

yet refer to a detailed local chronology, <strong>the</strong> Cornish <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> tends to be divided at present<br />

into an Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, to around 400 BC, <strong>and</strong> a Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, <strong>and</strong> this simple scheme<br />

will be used in this paper.<br />

In Britain, iron gradually replaced bronze for all <strong>the</strong> main metal necessities of life, for <strong>the</strong><br />

tools of fighting <strong>and</strong> farming, <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> 7th century BC. A date around 600 BC may<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore be appropriate for <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> Cornish <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>. Few iron objects survive<br />

in <strong>the</strong> acid local soils <strong>and</strong> all belong to <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>. <strong>Iron</strong> smelting on a comparatively<br />

extensive scale has been identified at Trevelgue, <strong>and</strong> it is possible that iron from <strong>the</strong> South<br />

West was reaching Danebury hillfort in Hampshire by <strong>the</strong> 6th century BC (Salter <strong>and</strong><br />

Ehrenreich, 1984, 151 —2). Traditionally, changes in pottery <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> introduction of hillforts<br />

havebeen used to identify <strong>the</strong> beginnings of a local <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> in which iron objects were sparse.<br />

Pottery of <strong>the</strong> Cornish Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> (formerly <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> A) is generally undecorated <strong>and</strong><br />

includes a range of shouldered jars <strong>and</strong> bowls as at Bodrifty (Dudley, 1956) which are<br />

regarded as copies of metal vessels first introduced <strong>during</strong> Late Bronze <strong>Age</strong> II, in <strong>the</strong> 8th<br />

century BC (Pearce, 1983, 90). It seems reasonable to assume that <strong>the</strong> pottery copies started<br />

somewhere in Britain <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> currency of <strong>the</strong> bronze forms. In Wessex where sufficient<br />

data exist for a detailed chonological ceramic sequence, it can be shown that some pottery<br />

formerly regarded as '<strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>' belongs to <strong>the</strong> closing stages of <strong>the</strong> Bronze <strong>Age</strong> (Cunliffe,<br />

1983). In <strong>Cornwall</strong>, <strong>the</strong> range of sites producing Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> pottery has not been greatly<br />

increased in recent years. To <strong>the</strong> open hut-circle settlements at Bodrifty (Dudley, 1956) <strong>and</strong><br />

at Garrow (Dudley, 1958, 48) have been added Sperris Croft <strong>and</strong> Wiccca Round in West<br />

Penwith (Dudley, 1958a), possibly Glendorgal, near Newquay (Dudley, 1962), <strong>and</strong> Kynance<br />

Gate (I. Thomas, 1960). Scatters of material on <strong>the</strong> north coast summarised by Dudley (1958)<br />

now include material from Gwithian (Thomas, 1964, Fig 21). Maen Castle <strong>and</strong> Trevelgue<br />

cliff castles remain <strong>the</strong> only fortified sites producing Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> pottery. In <strong>the</strong> present<br />

state of knowledge <strong>the</strong>se sites may date anywhere between about 800 <strong>and</strong> 400 BC, before<br />

or after <strong>the</strong> introduction of iron. The term Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, when applied to, or derived<br />

from, pottery in <strong>Cornwall</strong>, in fact means Late Bronze <strong>Age</strong>/Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>. This confusing<br />

situation will not be resolved until <strong>the</strong>re are fur<strong>the</strong>r sites with a radiocarbon based<br />

chronology. An added confusion for readers of local archaeological literature is <strong>the</strong> use in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1950s <strong>and</strong> 1960s of <strong>the</strong> term 'Early <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>' for <strong>the</strong> whole of <strong>the</strong> pre-Roman <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong><br />

(eg Thomas, 1958, 15).<br />

The introduction of hillforts is now known to have occurred <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> Later Bronze <strong>Age</strong><br />

in some parts of <strong>the</strong> country, particularly in Wales (Harding, 1976). Some Cornish sites may<br />

belong to an early stage in <strong>the</strong> local hillfort sequence, but it is impossible to say whe<strong>the</strong>r this<br />

began in <strong>Cornwall</strong> before or after <strong>the</strong> advent of iron. Early sites might be sought among<br />

simple univallate structures in good defensive positions such as Cadsonbury, near Callington,<br />

or <strong>the</strong> stone walled, moorl<strong>and</strong> enclosures, termed 'tor enclosures' by Silvester (1979, 188),<br />

such as Stowe's Pound, Minions, or Trencrom near St Ives. Recent examination of <strong>the</strong><br />

112

pottery from Trevelgue confirms <strong>the</strong> amount of Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> material present at this cliff<br />

castle <strong>and</strong> raises <strong>the</strong> possibility that <strong>the</strong> site may have been occupied from a date in <strong>the</strong> Late<br />

Bronze <strong>Age</strong>.<br />

The reasons for <strong>the</strong> scrappy evidence for <strong>the</strong> period 600-400 BC, <strong>the</strong> Cornish Earlier <strong>Iron</strong><br />

<strong>Age</strong>, probably relate to two linked factors. Climatic <strong>and</strong> soil changes <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> first<br />

millennium BC (Bell, 1984, 53) are thought to have caused major shifts in settlement<br />

patterns, although Bodmin Moor, at a lower altitude, may have been less affected than<br />

Dartmoor. If population levels were low <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> main pattern of settlement was one of simple<br />

circular houses scattered among field systems in areas which do not today survive as<br />

moorl<strong>and</strong>, sites will prove extremely difficult to detect.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> new pottery forms were adopted. Vessels are smaller than<br />

preceding types <strong>and</strong> tend to be better made; <strong>the</strong> most common form is a necked jar, often<br />

decorated with a zone of incised geometric or curvilinear pattern on <strong>the</strong> shoulder. This<br />

pottery has long been related to ceramic trends among La Tene groups in nor<strong>the</strong>rn France<br />

<strong>and</strong> appears in <strong>the</strong> Cornish literature ei<strong>the</strong>r as 'South Western Third B' (from an elaboration<br />

by Hawkes (1960, 15) of his original ABC system) or as 'Glastonbury Ware' from its occurrence<br />

in large quantities on <strong>the</strong> so-called Somerset Lake Village. This pottery occurs<br />

throughout <strong>Cornwall</strong> <strong>and</strong> Devon <strong>and</strong> into Somerset as far north as Mendip, but is hardly<br />

found in Dorset. Dating has varied, but it was generally assigned to <strong>the</strong> 2nd <strong>and</strong> 1st centuries<br />

BC. Recent excavations with radiocarbon dates have improved our underst<strong>and</strong>ing of its<br />

chronology <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> term `(La Tene) South-Western Decorated' is now coming into use for it.<br />

Detailed study of <strong>the</strong> pottery excavated at Cam Euny 1964 —72 (Elsdon, 1978) has<br />

identified sherds with stamp decoration, probably related to material from 5th century<br />

Brittany (Schwappach, 1969, 272); similar sherds occur at Trevelgue. The similarity with<br />

<strong>the</strong> Breton material <strong>and</strong> an associated radiocarbon date of 420 ± 70 bc (HAR-238) at Cam<br />

Euny suggest a 5th, or possibly 4th, century date for <strong>the</strong>se decorative beginnings. Avery<br />

(1972; 1973) has made a detailed study of South-Western Decorated pottery, based for<br />

<strong>Cornwall</strong> mainly on <strong>the</strong> excavations at Trevelgue <strong>and</strong> Castle Dore. Both at Cam Euny <strong>and</strong><br />

at Castle Dore, <strong>the</strong>re is material with rouletted decoration which appears to represent <strong>the</strong> next<br />

ceramic phase after <strong>the</strong> stamp-decorated sherds. Avery <strong>and</strong> Elsdon both place this rouletted<br />

pottery in <strong>the</strong> 3rd century BC, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> start of <strong>the</strong> much more common incised geometric<br />

<strong>and</strong> curvilinear decorated material in <strong>the</strong> second century. Excavations at Killibury hillfort,<br />

Egloshayle, in 1975-6 (Miles et al, 1977) produced a series of radiocarbon dates which<br />

suggested that South-Western Decorated pottery, including its curvilinear decoration, was<br />

fully developed by <strong>the</strong> 3rd century BC. The Killibury dates appear to be corroborated by a<br />

series from Meare, Somerset (Coles, 1981, 68). It would not be ureasonable to suggest that<br />

South-Western Decorated pottery was developing <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> 4th century BC, relegating <strong>the</strong><br />

sparsely occurring rouletted material to <strong>the</strong> (earlier?) 4th century BC. South-Western<br />

Decorated pottery occurs on a wide range of sites <strong>and</strong> in far greater quantities than all Earlier<br />

<strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> styles, <strong>and</strong> a possible 4th century origin both explains its comparative frequency<br />

<strong>and</strong> allows an extended chronology for <strong>the</strong> sites concerned.<br />

For convenience, <strong>the</strong> period from c. 400 BC <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> introduction of <strong>the</strong> decorated styles<br />

will be referred to as <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>. This revision of chronology suggests a period of<br />

fairly rapid ceramic change in <strong>the</strong> 5th <strong>and</strong> 4th centuries BC <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n a stable period, in which<br />

pottery was produced without detectable change, lasting until <strong>the</strong> 1st century BC.<br />

This stability may be associated with changes in production centres <strong>and</strong> distribution.<br />

Peacock (1968, 1969) demonstrated that virtually all South-Western Decorated pottery from<br />

<strong>Cornwall</strong> contains minerals derived from <strong>the</strong> gabbroic rocks of <strong>the</strong> St Keverne area of <strong>the</strong><br />

113

Lizard, <strong>and</strong> distinguished this as Group I, while o<strong>the</strong>r decoratively similar pottery had<br />

petrology which indicated origins in Devon <strong>and</strong> in Somerset. The Cam Euny material shows<br />

a gradual change from presumably local granitic fabrics to gabbroic wares, with <strong>the</strong> majority<br />

of <strong>the</strong> South-Western Decorated pottery being gabbroic. South-Western Decorated pottery<br />

from o<strong>the</strong>r sites in West Penwith, such as Bodrifty, appears to be gabbroic, Peacock's Group<br />

I. Fur<strong>the</strong>r east in <strong>Cornwall</strong>, South-Western Decorated pottery is exclusively of gabbroic<br />

fabric, even at Castle Dore, or at Killibury 50 km from <strong>the</strong> suggested source. Occasional<br />

sherds are found in Devon. Despite an intensive programme of field walking by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Cornwall</strong><br />

<strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> (CAS) between 1978 <strong>and</strong> 1983, no evidence of pottery manufacture<br />

in <strong>the</strong> gabbroic area has been identified (CAS Newsletters, Nos 28-40). However, <strong>the</strong> area<br />

produced more gabbroic sherds as surface finds than <strong>the</strong> Kenwyn valley north of Truro<br />

which was walked in 1983-4 (CAS Newsletters, Nos 43-44). If <strong>the</strong> pottery was clampfired,<br />

manufacture would leave little trace, particularly as overfired or continually reheated<br />

sherds tend to crumble (pers.comm. on material from Trethurgy). For <strong>the</strong> Neolithic gabbroic<br />

pottery found at Cam Brea, it has recently been suggested that appropriate suites of minerals<br />

could be found in <strong>the</strong> Camborne area (Mercer, 1981, 179). The location of <strong>the</strong> production<br />

centre(s) is unlikely to be finally settled until ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> sites <strong>the</strong>mselves are found, or a great<br />

deal more detailed petrological work is done, both on potential source areas <strong>and</strong> on possible<br />

variations within <strong>the</strong> gabbroic fabric. For <strong>the</strong> present, however, it appears a reasonable hypo<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

that, <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, pottery manufacture gradually became <strong>the</strong> exclusive<br />

preserve of groups resident on <strong>the</strong> Lizard <strong>and</strong> that gabbroic pottery was distributed through<br />

exchange networks which became more sophisticated <strong>and</strong> extensive towards <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>.<br />

The <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>and</strong> Roman periods in <strong>Cornwall</strong> have been covered by two general studies<br />

of <strong>the</strong> region (Fox 1964, 2nd ed. 1973; Pearce, 1981). A more detailed study by Thomas<br />

(1966) entitled 'The Character <strong>and</strong> Origins of Roman Dumnonia' covered settlement patterns<br />

<strong>and</strong> emphasised <strong>the</strong> cultural poverty of Dumnonia compared to o<strong>the</strong>r areas of sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Britain. Hillforts have been discussed by Forde-Johnson (1976, 30-5). More recently, an<br />

analysis of enclosed <strong>and</strong> defended settlements by Johnson <strong>and</strong> Rose (1982) provided a comprehensive<br />

summary of <strong>the</strong> evidence to date, made graphic with 290 plans. Fox had<br />

demonstrated (1952) that multivallate hillforts with close-spaced ramparts were virtually<br />

absent from <strong>the</strong> South West, <strong>and</strong> that multiple enclosure sites with wide-spaced ramparts<br />

occurred instead. She discussed <strong>the</strong> multiple enclosure sites fur<strong>the</strong>r in 1958 (Fox, 1961),<br />

emphasising <strong>the</strong> wide variety both in plan <strong>and</strong> in geographical location, a variety fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

brought out by Johnson <strong>and</strong> Rose (1982). Multiple enclosure forts occur throughout Devon<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Cornwall</strong> <strong>and</strong> in South Wales, with occasional examples elsewhere. Fox (1961, 46)<br />

suggested that <strong>the</strong> form was related to <strong>the</strong> needs of a pastoral, principally cattle rearing,<br />

economy. No convincing alternative has yet been suggested, <strong>and</strong> no research design has been<br />

carried out to test this hypo<strong>the</strong>sis.<br />

By 1958, excavations at Tregeare Rounds, Castle Dore <strong>and</strong> Chun Castle, toge<strong>the</strong>r with<br />

sites in Devon, had all produced pottery of <strong>the</strong> South-Western Decorated type. A Later <strong>Iron</strong><br />

<strong>Age</strong> dating for multiple-enclosure hillforts has been confirmed by excavations at Killibury<br />

(Miles et al, 1977) <strong>and</strong> at Castle-an-Dinas, St Columb Major (Wailes, 1963), although <strong>the</strong><br />

final report on <strong>the</strong> latter site is still awaited. With <strong>the</strong> exception of Cam Brea (Mercer, 1981),<br />

no o<strong>the</strong>r non-coastal hillfort has been excavated in <strong>the</strong> last 25 years. At Cam Brea, while<br />

hut cicles were undoubtedly occupied <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, <strong>the</strong> defences were<br />

tentatively assigned to <strong>the</strong> Neolithic period. The work at Killibury, although on a small scale,<br />

was valuable in demonstrating dense occupation in <strong>the</strong> inner enclosure, with 13 possible<br />

structural phases between <strong>the</strong> 4th <strong>and</strong> 1st centuries BC/AD, while occupation in <strong>the</strong> outer<br />

114

enclosure was apparently scantier. The 1936-37 excavations at Castle Dore (Radford, 1951)<br />

had shown permanent timber structures, perhaps with some degree of planned layout, but <strong>the</strong><br />

features were sparse compared to <strong>the</strong> density at Killibury. This comparative sparsity, toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

with o<strong>the</strong>r evidence, suggests that Castle Dore had phases of disuse (Quinnell <strong>and</strong> Harris,<br />

1985). Both Killibury <strong>and</strong> Castle Dore have four-post structures, probably grain storage<br />

units, of a type that was not previously thought to occur in <strong>Cornwall</strong>. There is ano<strong>the</strong>r of<br />

Roman date at Trethurgy (Quinnell, forthcoming). Hillforts as permanently occupied<br />

centres — albeit deserted for periods as local patterns of power changed — <strong>and</strong> hillforts with<br />

a degree of interior planning, incorporating both round timber houses <strong>and</strong> rectangular storage<br />

units, are concepts consistent with our present underst<strong>and</strong>ing of <strong>the</strong>se monuments in Britain<br />

as a whole (Cunliffe, 1984).<br />

Cliff castles — fortified promontories — have tended to be regarded as a special Cornish<br />

feature, perhaps initiated by Breton immigrants (Cotton, 1959; Thomas, 1966, 78). A recent<br />

study by Lamb (1980, Fig 1) has emphasised that this hillfort variant occurs both in <strong>the</strong><br />

British Isles <strong>and</strong> in nor<strong>the</strong>rn France wherever <strong>the</strong> geography of <strong>the</strong> coast line is suitable.<br />

Maen Castle <strong>and</strong> Trevelgue have been mentioned above as occupied <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> Earlier <strong>Iron</strong><br />

<strong>Age</strong>. Trevelgue certainly continued in <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> as well, <strong>and</strong> has produced a large<br />

collection of both Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>and</strong> South-Western Decorated pottery but very little<br />

Cordoned Ware <strong>and</strong> none that need be of pre-Roman date. It has <strong>the</strong> most complex defences<br />

of any Cornish cliff castle, yet its floruit appears to have been before c. 50 BC. CAS excavations<br />

at The Rumps, St Minver (Brooks, 1974) between 1963 <strong>and</strong> 67 showed occupation<br />

associated with South-Western Decorated pottery (including rouletted sherds) <strong>and</strong> Cordoned<br />

Ware, with a potential date range from <strong>the</strong> 4th century BC to <strong>the</strong> 1st century AD. The<br />

defences at The Rumps had undergone substantial alteration <strong>during</strong> this period, <strong>and</strong> round<br />

timber houses similar to those in inl<strong>and</strong> hillforts <strong>and</strong> settlements were identified. In 1983,<br />

work at Penhale cliff castle, Perranzabuloe (Smith, 1984) yielded a single round house <strong>and</strong><br />

South-Western Decorated pottery within a large excavated area; radiocarbon dates are<br />

awaited. Inconvenient though <strong>the</strong>se fortified promontory sites may appear to modern eyes,<br />

it is now well established that <strong>the</strong>y were permanent settlements of varying duration, which in<br />

excavated detail may not differ from inl<strong>and</strong> hillforts. Misty ideas of temporary refuges have<br />

to be discounted, while <strong>the</strong>ir wide date-range shows that <strong>the</strong>y cannot be explained as <strong>the</strong><br />

product of one historical event, such as immigrant Veneti fleeing <strong>the</strong> Roman conquest of<br />

Gaul. This long chronological range <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> wide variation of <strong>the</strong>ir defences suggest that <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship of <strong>the</strong>ir inhabitants to those of nearby settlements may have taken different forms<br />

<strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>.<br />

Small univallate enclosures, known in <strong>Cornwall</strong> as 'rounds', were scarcely recognized or<br />

understood in 1958 (Dudley, 1958). They may lie on hillslopes, or o<strong>the</strong>r not obviously<br />

defensible positions; <strong>the</strong>ir ditches tend to be shallow, 1.5 to 2m deep (though <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

exceptions) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir entrances are simple without inturns. The parish check-list programme of<br />

<strong>the</strong> CAS has greatly increased <strong>the</strong> numbers known. Thomas, in <strong>the</strong> first general published<br />

discussion on rounds (1966, 88), suggested a potential total of 750 for Devon <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cornwall</strong>.<br />

This figure is likely to be an underestimate as aerial photography is now producing new sites<br />

(Johnson <strong>and</strong> Rose 1982; Griffith, 1985). Johnson <strong>and</strong> Rose have shown that rounds have<br />

considerable complexity <strong>and</strong> variation in plan <strong>and</strong> can exist in close proximity, for example<br />

<strong>the</strong> pair on <strong>the</strong> slopes of Tregonning Hill below Castle Pencaire. About' fifteen Cornish<br />

rounds have now been excavated to a greater or lesser (minimal) extent <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir occupation<br />

ranges in date from <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> to c. AD 600. The interior of Threemilestone, near<br />

Truro, was about three quarters excavated <strong>and</strong> is <strong>the</strong> only round so far demonstrated to have<br />

115

St.Mawgan V<br />

....',.. - •<br />

•'' Orti°<br />

/ 49.adij<br />

i .01.Pr°<br />

Cain Euny Al<br />

4c0°•,; NI)<br />

• 0 ID<br />

• itt%•Pl°e' q■<br />

,<br />

e • HP • ge(5.70<br />

,<br />

•<br />

,v,,<br />

*te:013 Actro?6,'s<br />

&WA c;,,; ',<br />

• a • ',, o •,g,'5-41<br />

vs . e • ge°4'rejl<br />

:141.4'64v<br />

s - - - - . 4(0E'<br />

- - - - -11q5;40.4S0e4 • '<br />

St.Mawg-an W<br />

Ft<br />

10 20 30<br />

0 5 10<br />

Fig 2<br />

Bodrifty House E, Earlier <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> (after Dudley); Castle Dore Hut 4, 4th or 3rd century BC (?) (after Radford);<br />

Trevisker House 1, 1st centuries BC/AD (after Greenfield); Cam Euny House Al, 4th century BC or later (after<br />

Christie); St Mawgan-in-Pydar Houses W <strong>and</strong> V (latest phase) 1st century AD (after 77zreipl<strong>and</strong>).<br />

116

een occupied entirely within <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> (Dudley, 1960; Schweiso, 1976). The plan<br />

shows dense occupation with timber houses in <strong>the</strong> centre as well as around <strong>the</strong> perimeter.<br />

The round at Trevisker, St Eval (ApSimon <strong>and</strong> Greenfield, 1972) was initially small,<br />

enclosing c. 0.1 ha with a timber round house 13 m across. Material on <strong>the</strong> floor of this house<br />

produced a radiocarbon date of 180 ± 90 bc (NPL —135). This phase was associated with<br />

South-Western Decorated pottery but was replaced, within <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, by a far larger<br />

enclosure of c. 1.2 ha <strong>and</strong> at least one large timber round house (Fig 2). Some occupation<br />

at Trevisker continued until <strong>the</strong> 2nd century AD. Castle Gotha round, near St Austell, also<br />

had a date range from <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> until <strong>the</strong> 2nd, or possibly 3rd, century AD<br />

(Saunders <strong>and</strong> Harris, 1982).<br />

The <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> house plans so far recorded in <strong>Cornwall</strong> are circular, with an inner ring of<br />

posts taking <strong>the</strong> main weight of <strong>the</strong> roof, <strong>and</strong> an outer wall of granite blocks, shale, turf or<br />

timber depending on <strong>the</strong> locality. Stone-walled houses such as those at Bodrifty (Fig 2) are<br />

identical in plan to those found in <strong>the</strong> local Bronze <strong>Age</strong>, while <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> houses at<br />

Trevisker is comparable with <strong>the</strong> largest found elsewhere in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Britain. Reconstruction<br />

work by Reynolds on round houses of this size, using straw thatch, has shown in detail how<br />

<strong>the</strong>y might have looked (Reynolds, 1978; 1982).<br />

The relationship of a round to a field system was demonstrated at Goldherring, Sancreed<br />

(Guthrie, 1969). This round, built initially in <strong>the</strong> first century AD <strong>and</strong> containing smallish<br />

round houses, was set in a block of small rectangular fields. Fieldwork <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> study of air<br />

photographs carried out since <strong>the</strong> late 1970s by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Cornwall</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> Unit (formerly<br />

<strong>Cornwall</strong> Committee for Rescue Archaeology) show traces of field systems regularly<br />

appearing around such sites, wherever conditions permit <strong>the</strong>ir survival (Johnson <strong>and</strong> Rose,<br />

1982; <strong>Cornwall</strong> Committee for Rescue Archaeology Reports 1977 onward). The full implications<br />

of this fieldwork, which is still continuing, have yet to be assessed. Fields indicate<br />

arable farming. Evidence for specific cereal production is sparse, because no proper wet<br />

sieving <strong>and</strong> analysis programme has yet been carried out. Hordeum spp. (barley), Avena spp.<br />

(wild or cultivated oats) <strong>and</strong> Secale cereale (rye) were recorded at Goldherring (Guthrie,<br />

1969, 38), Triticum dicoccum (emmer), T. spelta (spelt) <strong>and</strong> Avena sp. at Killibury<br />

(Hillman, G. in Miles et al, 1977). Pollen analysis suggested arable farming around Cam<br />

Euny, where traces of fields survive around <strong>the</strong> unenclosed settlement (Christie, 1978, 311,<br />

426). Querns are found on all types of settlement site. Rotary querns were introduced into<br />

<strong>Cornwall</strong> in <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, as in to <strong>the</strong> remainder of Britain (eg Trevisker, ApSimon<br />

<strong>and</strong> Greenfield, 1972, 349) but .,addle querns continued to be used as well, <strong>and</strong> both types<br />

are found throughout <strong>the</strong> Roman period. Detailed underst<strong>and</strong>ing of settlement patterns <strong>and</strong><br />

farming practices awaits fur<strong>the</strong>r work on macroscopic plant remains <strong>and</strong> pollen analysis. It<br />

must also depend on more detailed knowledge of <strong>the</strong> relationship of rounds <strong>and</strong> hillforts to<br />

<strong>the</strong> unenclosed settlements, which remain elusive throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>. That at Cam Euny<br />

was located because it underlay a later settlement of courtyard houses.<br />

The variations in enclosed <strong>and</strong> fortified sites presented by Johnson <strong>and</strong> Rose (1982)<br />

indicate complex social patterns varying through time. The rounds have been seen as <strong>the</strong><br />

settlements of l<strong>and</strong>owning kindred groups (Fox, 1964, 125). Multiple enclosure hillforts<br />

should represent an upper social stratum of chiefs. The extent of defences on some larger<br />

sites indicates control of considerable man power. Cattle have been seen as <strong>the</strong> basis of wealth<br />

for <strong>the</strong>se chiefs, but sheep, better suited to South Western upl<strong>and</strong> grazing, should also be considered<br />

as an important local resource. Grazing for ei<strong>the</strong>r implies considerable tracts of l<strong>and</strong><br />

controlled from multiple enclosure hillforts. Ano<strong>the</strong>r possibility would be areas of arable<br />

worked by bondmen, a system foreshadowing <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>holding system of Early Medieval<br />

Wales. The occupants of rounds may have paid dues in kind or labour. It is probable that<br />

117

a combination of all <strong>the</strong>se resources contributed to <strong>the</strong> position of hillfort-building chiefs.<br />

Material wealth, represented by archaeological finds, still seems to have been less than that<br />

evidenced elsewhere in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Engl<strong>and</strong>, but perhaps has been underestimated. No new<br />

pieces of decorated metalwork have been found since 1958 although a study of <strong>the</strong> Trenoweth<br />

collar (Megaw, 1967) relocates its findspot to St Stephen-in-Brannel.<br />

The univallate hillslope fort of St Mawgan-in-Pydar (c. 1.2 ha) near Newquay (Threipl<strong>and</strong><br />

1956) hints at a different kind of social unit to those represented by rounds or multiple<br />

enclosure hillforts. Despite its small size, its entrance had an elaborate unturn, a feature<br />

lacking in rounds, <strong>and</strong> it produced a rich array of finds, including a decorated shield<br />

mounting. The date of occupation may have been from c. 100 BC to AD 100. Thus, unlike<br />

<strong>the</strong> multiple-enclosure hillforts, it continued after <strong>the</strong> Roman occupation.<br />

The dead of <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>Cornwall</strong> are less well represented than <strong>the</strong> living, yet compared<br />

to most of Britain <strong>the</strong> evidence is good. <strong>Cornwall</strong> is one of <strong>the</strong> few areas to have produced<br />

cemeteries. Those at Harlyn Bay <strong>and</strong> at nearby Trevone (Dudley, 1965) have long been<br />

known, as have <strong>the</strong> smaller sites at Trelan Bahow in <strong>the</strong> Lizard, Stamford Hill outside<br />

Plymouth <strong>and</strong> related sites in <strong>the</strong> Isles of Scilly. These sites are all dateable as graves have<br />

produced decorated metal artefacts, especially brooches <strong>and</strong> mirrors, ranging in date from<br />

<strong>the</strong> 3rd century BC to <strong>the</strong> 1st century AD. O<strong>the</strong>r cemeteries such as Crantock without<br />

dateable artefacts may also be of <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> date (Whimster, 1977, 81). Whimster's excavation<br />

at Harlyn Bay in 1975 showed that <strong>the</strong>re may have been a circular stone temple in <strong>the</strong> vicinity<br />

of <strong>the</strong> cemetery (1977, 69). Whimster's work at Harlyn Bay formed part of a major study<br />

of burial practices in <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> Britain (1977a, 181). He was able to demonstrate <strong>the</strong> regular<br />

pratice of crouched inhumation with head to <strong>the</strong> north in <strong>Cornwall</strong>, as in scattered burials<br />

across Wessex, <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> Yorkshire cemeteries which include 'chariot' burials. Until<br />

Whimster's study, <strong>the</strong> south-western cemeteries had been linked to those in Brittany because<br />

of <strong>the</strong> presence of long stone cists in both areas. But in Brittany <strong>the</strong> burial rite was extended<br />

inhumation. The Cornish cemeteries seem to be showing us a British funerary tradition made<br />

archaeologically visible by <strong>the</strong> use of long stone cists. Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> stone cists, using local<br />

slate, reflect Breton influence, is an unanswerable question at present. It must be doubtful<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re was any Breton influence on <strong>the</strong> religious practices of <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>Cornwall</strong>. The<br />

Breton evidence, conveniently summarized in Giot (1960), emphasises <strong>the</strong> importance of<br />

carved stone pillars (lec'hs). None have ever been noted in <strong>Cornwall</strong>, despite <strong>the</strong> present<br />

author's hopeful examination of st<strong>and</strong>ing stones over <strong>the</strong> past fifteen years.<br />

Both religious practices <strong>and</strong> Breton connections enter consideration of <strong>the</strong> souterrains or<br />

logous' of West <strong>Cornwall</strong>. A useful factual summary was published by Clark in 1961.<br />

Cornish souterrains differ from <strong>the</strong>ir Breton counterparts in <strong>the</strong>ir method of construction.<br />

They are constructed of stone in open trenches, whereas Breton soutterains are entirely tunnelled<br />

out; in this respect Cornish examples are similar to those in Scotl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> in Irel<strong>and</strong>.<br />

It is becoming increasingly aparent that souterrains in all <strong>the</strong>se areas are closely linked to<br />

settlements <strong>and</strong> are not isolated monuments. Thomas (1972) argued that souterrains were<br />

used for storage, drawing on <strong>the</strong> similarities with <strong>the</strong> medieval <strong>and</strong> later West Cornish 'hulls',<br />

a point also brought out in a comprehensive survey of hulls by Tangye (1973). A throughdraught<br />

may have been provided by small gaps in <strong>the</strong> end opposite <strong>the</strong> entrance, or in <strong>the</strong><br />

side passage.<br />

A detailed examination of <strong>the</strong> Cam Euny fogou <strong>and</strong> associated 'round chamber' was<br />

carried out by Christie (1978) <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1964-72 excavation programme. The 'round<br />

chamber' with a short entrance passage proved to be <strong>the</strong> earliest feature of <strong>the</strong> complex; it<br />

was thought ei<strong>the</strong>r to have had a timber roof or to have remained open. A stamped-decorated<br />

sherd similar to those found in a feature elsewhere on <strong>the</strong> site with a radiocarbon date of<br />

118

420±70 be (HAR —238) suggested a possible 5th century BC date. The nature of any<br />

associated settlement at this early date was unclear. The 'long passage' with a probable<br />

entrance through <strong>the</strong> side was added later; a radiocarbon date of 130±80 be (HAR —334)<br />

from its floor was associated with a local variant of South-Western Decorated pottery. A<br />

settlement of round turf <strong>and</strong> timber houses <strong>the</strong>n clustered around <strong>the</strong> fogou, its starting date<br />

depending on that assigned to <strong>the</strong> associated South-Western Decorated pottery. Elsdon (1978,<br />

404) suggested <strong>the</strong> 3rd or 2nd centuries BC, but an origin in <strong>the</strong> 4th century BC would be<br />

possible if <strong>the</strong> back-dating of this pottery type suggested above is allowed. Finally, at Camn<br />

Euny an 'east entrance' was added to <strong>the</strong> 'long passage' when <strong>the</strong> first courtyard houses were<br />

built on <strong>the</strong> site, in <strong>the</strong> 1st century BC according to Elsdon (1975, 404) but more probably<br />

later (see below). The settlement <strong>and</strong> fogou continued in use until <strong>the</strong> 4th century AD. More<br />

recently Startin (1982) re-excavated Halligye fogou on <strong>the</strong> Lizard <strong>and</strong> also found evidence for<br />

multi-phase construction associated with a round, <strong>and</strong> a date range from <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong><br />

until a blocking in <strong>the</strong> Roman period. The dating evidence from Cam Euny <strong>and</strong> Halligye is<br />

consistent with that from earlier investigations in o<strong>the</strong>r fogous. It is not possible to show that<br />

any fogou was constructed before <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>. The end date for fogou construction<br />

is difficult; use of some like that at Porthmeor continued into <strong>the</strong> 4th century AD. The only<br />

cases in which a construction date within <strong>the</strong> Roman period is probable are those, as at<br />

Bossullow Trehyllys, where <strong>the</strong> fogou appears as an integral part of a courtyard house.<br />

Christie (1978, 332; 1979) reconsidered <strong>the</strong> purpose of Cornish souterrains, <strong>and</strong> favoured<br />

a religious function because of <strong>the</strong>ir impracticality of access, <strong>the</strong> narrow side passages or<br />

'creeps' <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> tantalizing implications of possible fragments of cremated human bone associated<br />

with <strong>the</strong> construction of <strong>the</strong> Cam Euny 'round chamber'. The modern mind tends to<br />

divide activities into modern categories. Is it not possible that storage of special commodities,<br />

food reserves (which would need to be immune from damp!), could have been linked to<br />

religious practices? The amount of Breton influence is difficult to assess, beyond <strong>the</strong> broader<br />

similarities. The Irish souterrains seem mainly to date to <strong>the</strong> Early Christian period, which<br />

weakens <strong>the</strong> argument for a general spread of <strong>the</strong> practice of souterrain construction from<br />

a single Breton source.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> 1st century BC a new form of pottery, 'Cordoned Ware', appears in <strong>Cornwall</strong><br />

(sometimes referred to by various <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> C labels). The fullest published range of<br />

Cordoned Ware is still that from St Mawgan-in-Pydar (Threipl<strong>and</strong>, 1956), though its study<br />

can be supplemented by <strong>the</strong> material from Carvossa, Probus excavated 1968 —70 (Douch <strong>and</strong><br />

Beard, 1970). Cordoned Ware has features which are also found in <strong>the</strong> pottery of nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

France <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> century preceding <strong>the</strong> Roman conquest of Gaul. A direct Breton origin was<br />

invoked by Thomas (1966, 79) but similarities are general ra<strong>the</strong>r than close <strong>and</strong> no imported<br />

Breton material has been found in <strong>Cornwall</strong>. Imported north French wares have been found<br />

in Dorset (principally at Hengistbury Head) <strong>and</strong> in Devon at Mount Batten (Cunliffe, 1983,<br />

125) <strong>and</strong> date to <strong>the</strong> years immediately preceding Caesar's conquest of Gaul (Cunliffe, 1982,<br />

50). Cordoned Ware may have originated as copies of this north French imported pottery,<br />

knowledge of which spread westwards with coastal trade, <strong>and</strong> if so may have started ei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

before Caesar's campaigns, or a little after while <strong>the</strong> imported forms were still current.<br />

Cornish Cordoned Ware is invariably of gabbroic fabric, suggesting that <strong>the</strong> new forms were<br />

adopted by <strong>the</strong> potting communities of <strong>the</strong> Lizard. The ware tends to be thinner <strong>and</strong> better<br />

made than South-Western Decorated pottery, improvements which have been attributed to<br />

<strong>the</strong> introduction of <strong>the</strong> potter's wheel. The present author is not convinced that any of this<br />

ware, or of <strong>the</strong> subsequent gabbroic forms of <strong>the</strong> Roman period, was wheelmade, <strong>and</strong>, until<br />

microscopic studies of particle alignment are available, suggests that 'wheel made' should<br />

be read as 'well made' for Cornish pottery.<br />

119

On most Cornish sites, even with modern excavations such as Killibury <strong>and</strong> The Rumps,<br />

it is not possible to separate stratigraphically South-Western Decorated pottery from<br />

Cordoned Wares (pace Threipl<strong>and</strong>, 1956, 53). There was some fusion — cordons appearing<br />

on South-Western Decorated pottery (eg Killibury P17, Miles et al, 1977) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> two styles<br />

were probably manufactured toge<strong>the</strong>r for a while. The actual terminal date for <strong>the</strong> manufacture<br />

of South-Western Decorated pottery is not yet established <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> style may have<br />

continued well into <strong>the</strong> 1st century AD. Goldherring (Guthrie, 1969) is <strong>the</strong> only site with a<br />

clearly defined stratified phase associated only with Cordoned Ware, <strong>and</strong> no South-Western<br />

Decorated or Roman forms. Threipl<strong>and</strong> emphasised in 1956 that Cordoned Ware was current<br />

until <strong>the</strong> 2nd century AD. Detailed analysis of <strong>the</strong> pottery from Trethurgy (Quinnell,<br />

forthcoming) makes it quite evident that large cordoned jars, with ei<strong>the</strong>r rolled (Type H) or<br />

everted (Type J) rims, were being made in <strong>the</strong> 3rd <strong>and</strong> 4th centuries AD. In fact is is probably<br />

only <strong>the</strong> bowls, Threipl<strong>and</strong>'s Type F <strong>and</strong> G, which can be restricted to <strong>the</strong> 1st centuries<br />

BC/AD: interestingly she notes (1956, 53) that <strong>the</strong>se are concentrated early in <strong>the</strong> sequence<br />

at St Mawgan-in-Pydar. Cordoned Ware should be regarded as a long lasting ceramic tradition<br />

<strong>and</strong> not a chronological horizon. Many sites have been dated in <strong>the</strong> past on <strong>the</strong> basis of<br />

a few sherds with cordons <strong>and</strong> need re-assessment. The courtyard house at Mulfra Vean<br />

(Thomas, 1963) has a pottery assemblage which contains large cordoned jars but also forms<br />

which would best belong in <strong>the</strong> 3rd century AD.<br />

If a starting date in <strong>the</strong> 1st century BC is accepted for Cordoned Ware, this still provides<br />

a useful terminus post quem, particularly in regard to <strong>the</strong> courtyard houses of West Penwith.<br />

These distinctive structures have small round <strong>and</strong> long rooms set within thick walls surrounding<br />

a central courtyard, generally regarded as unroofed (but see Christie, 1978, 387).<br />

Courtyard houses may form clusters of eight or so, with a central 'street' indicating an<br />

element of planning in <strong>the</strong> layout at Chysauster. Courtyard houses have still not been located<br />

anywhere but West Penwith <strong>and</strong> Scilly, despite superficial similarities with settlements in<br />

areas such as North Wales. They are best regarded as a local development, especially suited<br />

to local windswept conditions — <strong>the</strong> extensive contemporary field systems recorded in <strong>the</strong><br />

area by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Cornwall</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> Unit bear witness to <strong>the</strong> opening up of <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

The date of courtyard houses has been obscured by <strong>the</strong> presence of South-Western Decorated<br />

pottery on early excavations at Chysauster <strong>and</strong> Porthmeor. The Chysauster courtyard house<br />

settlement occurs in an area of fields with round houses, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> South-Western Decorated<br />

pottery could relate to earlier use of <strong>the</strong> site. Porthmeor occupies an earlier enclosure of <strong>the</strong><br />

round class. At Goldherring (Guthrie, 1969) <strong>the</strong> Cordoned Ware phase is associated with<br />

circular turf <strong>and</strong> timber houses within <strong>the</strong> round. The courtyard houses relate to a later<br />

occupation, in <strong>the</strong> 3rd <strong>and</strong> 4th centuries AD. At Cam Euny (Christie, 1978), courtyard<br />

houses were thought to have developed about <strong>the</strong> period when Cordoned Ware was<br />

introduced. But none of this ware is significantly stratified <strong>and</strong> all of it belongs to types with<br />

a long life span. The Cam Euny courtyard house phase could start much later, perhaps in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 2nd century AD <strong>and</strong> its sequence would <strong>the</strong>n be more consistent with that at Goldherring.<br />

It has already been suggested that <strong>the</strong> pottery from Mulfra Vean should be redated to <strong>the</strong> 3rd<br />

century AD. The bulk of <strong>the</strong> pottery from Chysauster dates to <strong>the</strong> 2nd/3rd centuries AD, <strong>and</strong><br />

from Porthmeor to <strong>the</strong> 3rd <strong>and</strong> 4th. Courtyard house hamlets or villages do not belong to<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, but to <strong>the</strong> Roman period. Visible surface remains often suggest <strong>the</strong>y have been<br />

built after a phase with round houses, as revealed by <strong>the</strong> recent <strong>Cornwall</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> Unit<br />

survey of Nanjulian, St Just in Penwith (CAU Report, January 1986), <strong>and</strong> may in general<br />

be less regular in layout than <strong>the</strong> 'classic' sites such as Chysauster (Wea<strong>the</strong>rhill, 1982).<br />

Possible influence from Brittany or north France can be seen in cliff castles, burial sites,<br />

fogous <strong>and</strong> pottery. While direct immigration (or 'invasion') on any scale is now discounted,<br />

120

it is only reasonable to accept that <strong>the</strong>re would be some similarities among groups who were<br />

in contact with each o<strong>the</strong>r across <strong>the</strong> English Channel. General similarities developing<br />

through contact are compatible with <strong>the</strong> long date range involved, from <strong>the</strong> Late Bronze <strong>Age</strong><br />

onwards. The main reason for this cross-channel contact was probably trade, particularly in<br />

Cornish tin. There have been several recent summaries of <strong>the</strong> archaeological <strong>and</strong> historical<br />

evidence for <strong>the</strong> pre-Roman Cornish tin trade (Laing, 1968; Cunliffe, 1983; Hawkes, 1984).<br />

In <strong>Cornwall</strong>, archaeological evidence continues to be slight. The unstratified <strong>and</strong> unpublished<br />

ingot from Castle Dore is probably <strong>the</strong> best established find of <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> date, now that <strong>the</strong><br />

St Mawes ingot has been assigned to <strong>the</strong> medieval period (Beagrie, 1983). Promising<br />

evidence is beginning to emerge from pollen studies of levels associated with tin working on<br />

Bodmin Moor. Those in <strong>the</strong> Colliford area may date well back into <strong>the</strong> prehistoric period<br />

(information, S. Gerrard). Research on material from Mount Batten in Plymouth Sound<br />

currently favours this location for ktis, <strong>the</strong> tin trading depot referred to by <strong>the</strong> Greek<br />

historian Diodorus Siculus (Cunliffe, 1983).<br />

The various classical references to Britain, both before <strong>and</strong> after <strong>the</strong> Roman conquest,<br />

were published in full by Rivet <strong>and</strong> Smith in 1979. These references provide <strong>the</strong> basis for<br />

assigning south-western Britain to a tribal group called <strong>the</strong> Dumnonii. They also explain why<br />

some at least of <strong>the</strong> inhabitants of <strong>Cornwall</strong> were called `Cornovii', providing an origin for<br />

<strong>the</strong> present name of <strong>Cornwall</strong> (1979, 325). Rivet <strong>and</strong> Smith provide a gazetteer of all classical<br />

records for place-names, settlements <strong>and</strong> geographical features throughout Britain <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

comments provide some fascinating sidelights on contemporary affairs — Belerion (L<strong>and</strong>'s<br />

End, p 266) incorporates an element meaning 'bright' or 'shining'. This may indicate a<br />

beacon at L<strong>and</strong>'s End as early as <strong>the</strong> 4th century BC, which would connect with <strong>the</strong> local<br />

importance of seafaring <strong>and</strong> navigation, whe<strong>the</strong>r coastal, to Scilly, or across <strong>the</strong> Channel.<br />

Underst<strong>and</strong>ing of <strong>the</strong> Roman conquest of south-west Britain has been dramatically<br />

advanced by <strong>the</strong> programme of excavations in Exeter from 1971. The presence of a fortress<br />

occupied by <strong>the</strong> Second Legion Augusta between c. AD 55 <strong>and</strong> AD 75 has been established<br />

(Bidwell, 1979; 1980). In Devon a programme of aerial survey has both greatly increased<br />

<strong>the</strong> number of Military sites known (seven forts, one marching camp, seven fortlets/signal<br />

stations), <strong>and</strong> shown that some, notably North Tawton <strong>and</strong> Okehampton, are multi-period<br />

(Griffith, 1984). No fort has yet been dated to <strong>the</strong> Claudian period (AD 43-54), <strong>and</strong> Bidwell<br />

(1980, 10) suggests that <strong>the</strong> military garrisoning of <strong>the</strong> South West occurred <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

governorship of Didius Gallus between AD 52 <strong>and</strong> 7. Presumably <strong>the</strong> Dumnonii did not pose<br />

any immediate threat to Rome. It is quite possible that <strong>the</strong> larger hillforts were out of use<br />

before <strong>the</strong> Romans arrived. Castle Dore <strong>and</strong> Killibury produced little Cordoned Ware<br />

(Quinnell <strong>and</strong> Harris, 1985, 128). Hembury, East Devon, was not occupied at <strong>the</strong> time of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Roman Conquest (Todd, 1984) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> end date of o<strong>the</strong>r excavated Devon hillforts cannot<br />

be closely established. Local shifts in power may have been brought about as <strong>the</strong> focus of<br />

trade with <strong>the</strong> continent moved from Wessex to eastern Engl<strong>and</strong> after <strong>the</strong> Roman conquest<br />

of Gaul. The event which caused <strong>the</strong> Roman military to garrison <strong>the</strong> South West <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

50s AD is unknown.<br />

So far only one Roman fort has been identified in <strong>Cornwall</strong>, <strong>the</strong> 1.0 ha site at Nanstallon,<br />

south of <strong>the</strong> River Camel, just west of Bodmin. Excavations between 1960 <strong>and</strong> 1963 by Fox <strong>and</strong><br />

Ravenhill (1972) showed that it had contained permanent timber buildings occupied between<br />

AD 55 — 60 <strong>and</strong> AD 75-80. The excavators interpreted <strong>the</strong> barrack accommodation as<br />

appropriate for a cohors quingenaria equitata, a mixed infantry <strong>and</strong> cavalry unit of some 500<br />

men. O<strong>the</strong>r forts in <strong>Cornwall</strong> will probably be identified as <strong>the</strong> current programme of aerial<br />

survey of <strong>the</strong> non-moorl<strong>and</strong> areas gets under way. It is possible that some Roman forts were<br />

sited within <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> hillforts, as has been demonstrated at Hembury in Devon (Todd, 1984),<br />

121

<strong>and</strong> so may not be detectable without excavation or geophysical survey. O<strong>the</strong>r forts may be<br />

grouped at present amongst <strong>the</strong> sub-rectangular enclosures of <strong>the</strong> county.<br />

These sub-rectangular earthworks, assumed to be a variant of rounds, were first<br />

summarised by Dudley (1954); known numbers have been recently increased by study of<br />

existing air photographs (Johnson <strong>and</strong> Rose, 1982). These enclosures are scattered throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> county, <strong>and</strong> occur in Devon, but with concentrations around <strong>the</strong> Helford River, <strong>the</strong> upper<br />

Fal valley <strong>and</strong> in north <strong>Cornwall</strong>. Trevinnick, near Wadebridge, was excavated by Fox <strong>and</strong><br />

Ravenhill (1969) to check whe<strong>the</strong>r it was a Roman military site, but proved to be an enclosed<br />

civilian settlement of <strong>the</strong> Roman period, not closely dateable. Grambla, near Wendron, a<br />

virtually square earthwork enclosing c. 0.35 ha in <strong>the</strong> Helford River area, was partly<br />

excavated in 1972 (Saunders, 1972). This also had been a civilian settlement, occupied from<br />

perhaps <strong>the</strong> 2nd century AD until <strong>the</strong> 6th; it contained distinctive oval houses. Its ditch was<br />

3m deep <strong>and</strong> its entrance had a quadrilateral setting of post-holes suggesting a gate tower.<br />

The 2 ha rectangular site at Carvossa, near Probus in <strong>the</strong> Fal valley, was excavated from<br />

1968 to 1970 (Douch <strong>and</strong> Beard, 1970; information from P.M. Carlyon). It produced a rich<br />

range of finds, starting with South-Western Decorated pottery. The samian sequence began<br />

with a single Tiberio-Claudian sherd, increased in <strong>the</strong> Neronian period, <strong>and</strong> continued with<br />

some fluctuation until <strong>the</strong> mid-second century Antonine period. The coin list <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

imports reinforce <strong>the</strong> pattern of <strong>the</strong> samian, suggesting that occupation still flourished in <strong>the</strong><br />

Hadrianic period <strong>and</strong> subsequently spanned <strong>the</strong> 2nd <strong>and</strong> 3rd centuries AD. The range of finds<br />

for <strong>the</strong> Neronian — Early Flavian period would be entirely appropriate for a military site.<br />

The stratigraphy was not clear <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re is some evidence for at least two earthwork phases.<br />

The main 2 ha earthwork had a ditch 4.5m deep which was not of military type, nor was<br />

<strong>the</strong> excavated east entrance. Features found in <strong>the</strong> interior, such as curvilinear gullies,<br />

suggest civilian occupation. The ditch had silted by at least 1.5m beneath <strong>the</strong> lowest samian<br />

sherd. The rectilinear earthwork may be suggested to be of pre-Roman date, perhaps as early<br />

as <strong>the</strong> 1st century BC. The finds indicate that activity continued throughout <strong>the</strong> suggested<br />

period of military occupation of <strong>Cornwall</strong>. A fort may have been established in part of <strong>the</strong><br />

earthwork complex, in which case most of <strong>the</strong> artefacts would derive from an external vicus.<br />

Perhaps some trusted chief was encouraged to develop at Carvossa a focus for trade up <strong>the</strong><br />

Fal valley. Alternatively, <strong>the</strong> finds may indicate a fort in <strong>the</strong> vicinity, perhaps within <strong>the</strong><br />

substantial earth-work of Golden one mile to <strong>the</strong> south. If Roman military occupation in<br />

<strong>Cornwall</strong> is demonstrated in future to be slight compared to that in Devon, a network of<br />

trusted local chiefs could be <strong>the</strong> reason. Ano<strong>the</strong>r local chief was allowed to continue<br />

occupation at St Mawgan-in-Pydar, where <strong>the</strong> range of small finds, imports <strong>and</strong> elaborate<br />

gabbroic pottery is second only to Carvossa. Carvossa certainly attracted traded artefacts. It<br />

also produced a rich range of gabbroic pottery, Cordoned wares <strong>and</strong> innovative pieces<br />

copying items such as a Dr 29 samian bowl <strong>and</strong> a bronze h<strong>and</strong>led patera. There was also<br />

evidence for metal-working, especially iron smelting in <strong>the</strong> ditch.<br />

If Carvossa was at one stage a military post, it will have been h<strong>and</strong>ed over to a local group<br />

c. AD 75. Here would be happening, on a small scale, <strong>the</strong> regular practice of turning over<br />

military bases to serve as local centres of administration <strong>and</strong> trade under Roman supervision.<br />

At Exeter this process led to <strong>the</strong> establishment of a cantonal capital. Isca Dumnoniorum,<br />

which administered both Devon <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cornwall</strong> (Bidwell, 1980, 56). There must have been<br />

a series of small centres throughout <strong>the</strong> South West. As no formal Roman building, apart<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Magor villa known since 1931, has been found in <strong>Cornwall</strong>, it may be presumed<br />

that such centres were generally developed in <strong>the</strong> local tradition. In <strong>Cornwall</strong> <strong>the</strong>se may be<br />

looked for amongst <strong>the</strong> more substantial small enclosures, where <strong>the</strong> descendants of chiefs —<br />

122

whose ancestors had occupied hillforts — administered <strong>the</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r parts of Dumnonia. Such<br />

centres would have been useful as local tax collection points, as <strong>the</strong> capital of <strong>the</strong> responsible<br />

civitas at Exeter was so distant.<br />

Trethurgy Al<br />

Trethurgy T2<br />

Ft<br />

10 20 310<br />

5 10<br />

Chysauster 5<br />

Castle Gotha<br />

Fig 3<br />

Trethurgy Houses Al <strong>and</strong> 72, late 2nd century AD; Chysauster Courtyard House 5, 3rd century AD (after<br />

Hencken); Castle Gotha Oval Hut, 2nd century AD (after Harris).<br />

123

The basic pattern of life does not appear to have changed much under Roman rule, but<br />

our underst<strong>and</strong>ing of it has greatly increased over <strong>the</strong> last 25 years (see Radford, 1958). The<br />

round continued as <strong>the</strong> main (detected) settlement type (Fox, 1964), 148; Fowler, 1976).<br />

Thomas emphasised this continuity in 1966, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack of evidence of much Roman<br />

influence on basic life styles. The main evidence for <strong>the</strong> continuance of rounds comes from<br />

Castle Gotha (Saunders <strong>and</strong> Harris, 1982), occupied from <strong>the</strong> Later <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> to <strong>the</strong> 2nd/3rd<br />

century AD; Trevisker (ApSimon <strong>and</strong> Greenfield, 1972), with activity until <strong>the</strong> 2nd century,<br />

<strong>and</strong> possibly Mer<strong>the</strong>r Euny (Thomas, 1968). During <strong>the</strong> 2nd century a number of new rounds<br />

were constructed: Shortlanesend (Harris, 1980), Carwar<strong>the</strong>n (Opie, 1939; unpublished<br />

material now in Truro Museum), Crane Godrevy (Thomas, 1968a), possibly Kilhallon<br />

(Carlyon, 1982), <strong>and</strong> Trethurgy (Quinnell, forthcoming). Of <strong>the</strong>se, Shortlanesend <strong>and</strong><br />

Kilhallon apparently had a short span of a century or so, <strong>and</strong> for Crane Godrevy only a small<br />

sample of pottery has been published (Thomas, 1964, 61). Carwar<strong>the</strong>n was occupied into <strong>the</strong><br />

4th century, Trethurgy into <strong>the</strong> 6th. The excavated sample is still small, but it is noteworthy<br />

that no round seems to have been continuously occupied from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

Roman period. Any dislocation in settlement patterns seems to have occurred in <strong>the</strong> 2nd<br />

century AD ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> 1st (perhaps related to <strong>the</strong> ending of occupation of <strong>the</strong> small<br />

hillfort at St Mawgan-in-Pydar) <strong>and</strong> to have been a gradual occurrence. The reasons are<br />

obscure. Was <strong>the</strong>re some historical event leading to temporary decline in population? Were<br />

<strong>the</strong>re changes in agricultural practice, brought about by new dem<strong>and</strong>s or new techniques? Did<br />

<strong>the</strong> establishment of new administration centres <strong>and</strong> communication patterns (though no<br />

Roman roads have yet been proved for <strong>Cornwall</strong>) ultimately cause shifts in settlement?<br />

It need occasion no surprise that minor fortifications were allowed under <strong>the</strong> Roman<br />

administration. Even minor defences were regarded in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> as a symbol of status.<br />

It was regular Roman practice to integrate <strong>the</strong> local upper classes in <strong>the</strong> administrative,<br />

military <strong>and</strong> economic structure of <strong>the</strong> Empire, <strong>and</strong> to encourage <strong>the</strong>m to continue to look<br />

after <strong>the</strong>ir own areas. The building of new rounds, <strong>and</strong> more substantial rectangular<br />

enclosures, implies <strong>the</strong> continuance of local traditions of maintaining order, <strong>and</strong> not<br />

necessarily a specific threat. However <strong>the</strong>re could be a link between <strong>the</strong> construction of new<br />

rounds, after a gap of about one hundred years, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> construction of fortifications around<br />

towns which occurred at Exeter in <strong>the</strong> late 2nd century (Bidwell, 1980, 66). Cornish rounds<br />

have been compared to <strong>the</strong> raths or enclosed settlements of south-west Wales, but recent work<br />

in <strong>the</strong> latter area has shown a significant difference. There, all excavated earth-works were<br />

constructed before <strong>the</strong> Roman occupation; some continued in use, but no new works were<br />

built. Gradually <strong>during</strong> <strong>the</strong> Roman period <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong>ir occupation changed, from dense<br />

concentrations of circular houses, to include single rectangular houses, as at Dan-y-Coed<br />

(Williams, 1985) <strong>and</strong> Walesl<strong>and</strong> Rath (Wainwright, 1971). This difference must reflect <strong>the</strong><br />

longer presence of <strong>the</strong> Roman army in Wales <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> establishment of an urban centre at<br />

Carmar<strong>the</strong>n. South-west Wales was left less to its local traditions than was south-west<br />

Engl<strong>and</strong>. In Dyfed <strong>the</strong>re are also several rectilinear enclosures, now proved to start in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong> in <strong>the</strong> case of Pen-y-Coed, Llangynog (Murphy, 1983), though Llangynog II <strong>and</strong><br />

possibly Castle Flemish were built in <strong>the</strong> Roman period (James <strong>and</strong> Williams, 1982, 299).<br />

The population of Roman Britain as a whole is now considered to have exp<strong>and</strong>ed rapidly,<br />

possibly even to around six million (Salway, , 1981, 554). It is reasonable to expect more later<br />

Roman sites in <strong>Cornwall</strong> than in <strong>the</strong> 1st to 2nd centuries. Dates given for sites which differ<br />

from those in <strong>the</strong> published reports are based on a current study of pottery from Carvossa<br />

(information P.M. Carlyon) <strong>and</strong> Trethurgy (Quinnell forthcoming), sites situated 15 km apart<br />

but which overlap chronologically to present a continuous sequence from <strong>the</strong> 1st century BC<br />

to 6th or 7th centuries AD. The number of rounds may have increased, <strong>and</strong> this increase may<br />

124

AL •r,<br />

.4 •eakitiocto dp° •<br />

• • kir w..s..- ny o<br />

bo ,:7 4iVal■pAiii.<br />

44,4,as• .. 40<br />

• )1F• a 4 gal I . , ...;-__. 'Z1<br />

•', so<br />

443.-0<br />

; 0<br />

Trethurgy T4<br />

1. ..1.1'..1.,,<br />

,<br />

. ,...„,„,,,<br />

...,„<br />

n ‘Nip.p ca<br />

,19. ..<br />

033 411? -.4?). V Vio8;ks<br />

... ' •°FliMeLft<br />

•■ •.<br />

q •<br />

0 d'on<br />

7.1_07L. OVv.elio<br />

e " ig1610 °,0<br />

-791 '4;6<br />

...oz,,;%•,.- , . 4,1,goq<br />

• C.,,C) CIP<br />

Trebarveth 3<br />

rvi<br />

5<br />

10<br />

•<br />

;',4;p'•<br />

el<br />

••<br />

.44<br />

A ■<br />

Uob 11-*<br />

r •<br />

9<br />

•<br />

,<br />

Porth Godrevy<br />

Ft<br />

0 10 20 30<br />

Fig 4<br />

Trethurgy Houses Z2 <strong>and</strong> T3, early 4th century AD; Grambla Building I (simplified,) 2nd century AD or later (after<br />

Saunders); Trebarveth 3, 3rd century AD (after Peacock); Porth Godrevv, 3rd century AD (after Fowler).<br />

125<br />

•

e matched by <strong>the</strong> development <strong>and</strong> proliferation of courtyard houses in West Penwith from<br />

<strong>the</strong> 2nd century AD. Isolated unenclosed houses are rare, Porth Godrevy (Fowler, 1962)<br />

occupied between <strong>the</strong> 2nd <strong>and</strong> 4th centuries being almost <strong>the</strong> only example (Fig 4); as with<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Iron</strong> <strong>Age</strong>, this scarcity may well be due to <strong>the</strong> difficulty of finding sites.<br />

Gradual changes can be detected in most aspects of life in Roman <strong>Cornwall</strong> which are<br />

archaeologically retrievable. It is difficult to show a true round house of <strong>the</strong> Cornish Roman<br />

period. At Trethurgy, Castle Gotha <strong>and</strong> Grambla (<strong>and</strong> possibly Crane Godrevy <strong>and</strong><br />

Shortlanesend) <strong>the</strong> houses were oval, up to 13m in length <strong>and</strong> providing 80-100 m2 of floor<br />

space. Posts, where present or detectable, were set in <strong>the</strong> wall face. Such houses must have<br />

had a ridged roof, supported probably on a polygonal wall plate. The ridged roof was<br />

presumably a local adaptation of Roman building styles. The new oval houses left <strong>the</strong><br />

interiors free of supporting posts <strong>and</strong> allowed a larger area to be roofed with shorter timbers<br />

than in a round house with similar floor space. The sequence is illustrated in Figs 3-4.<br />

Strong local tradition is still evident in <strong>the</strong> oval (as opposed to rectangular) plan which made<br />

good structural sense in terms of wind resistance. Smaller buildings like Porth Godrevy <strong>and</strong><br />

Trebarveth T3 (Peacock, 1969a) were also oval in plan. The large oval houses were well<br />

floored, with tamped rab (beaten earth) or paving kept clean. At Trethurgy, quantities of<br />

small nails suggest interior wooden fittings <strong>and</strong> furniture. A regular feature was a hearth pit<br />

or cooking pit, alongside a hearth. Hearth pits (especially at Trethurgy) had heavy burning<br />

around <strong>the</strong>ir tops <strong>and</strong> may have been used for slow cooking, with pots safely embedded in<br />

hot ashes below floor level as <strong>the</strong> fire died down.<br />

Trethurgy, near St Austell, is <strong>the</strong> only round of which <strong>the</strong> interior has been fully excavated<br />

(Miles <strong>and</strong> Miles, 1973). Precise chronology is difficult to establish because of <strong>the</strong> usual<br />

scarcity of dateable small finds. Occupation appears to start in <strong>the</strong> late 2nd century AD with<br />

three large oval houses set around its perimeter <strong>and</strong> a four post structure (a granary?). An<br />

area was provided for animal husb<strong>and</strong>ry <strong>and</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r for general activities <strong>and</strong> storage, one<br />

on ei<strong>the</strong>r side of <strong>the</strong> entrance; both areas continued throughout <strong>the</strong> three centuries or more<br />

that <strong>the</strong> site was occupied. By <strong>the</strong> early 3rd century, domestic provision had increased to five<br />

houses, one of <strong>the</strong>m small (Fig 5). This maximum residential capacity continued until <strong>the</strong><br />

early 4th century when <strong>the</strong>re may have been a short gap in <strong>the</strong> occupation. After this a<br />

rebuilding phase provided only four houses but a large byre was constructed in <strong>the</strong> animal<br />

husb<strong>and</strong>ry area. In <strong>the</strong> late 4th century, houses may again have increased to five, though <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

size tended to be smaller. During <strong>the</strong> 5th century accommodation gradually dropped to two<br />

or three houses.<br />

Sherds of over 600 vessels were found at Trethurgy, but most represented only small parts<br />