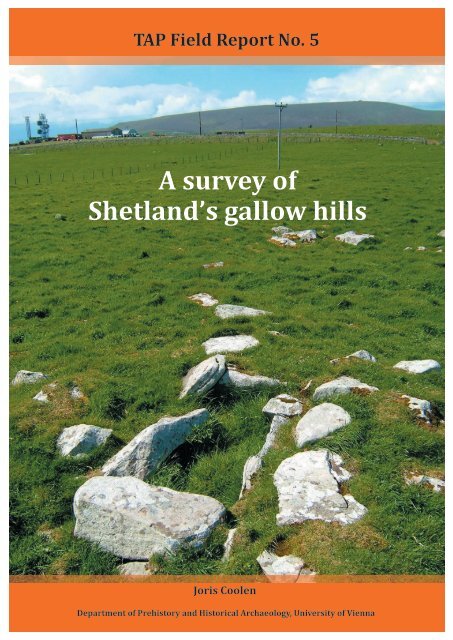

TAP Field Report No. 5 A survey of Shetland's gallow hills Joris ...

TAP Field Report No. 5 A survey of Shetland's gallow hills Joris ...

TAP Field Report No. 5 A survey of Shetland's gallow hills Joris ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5A <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong>Shetland’s <strong>gallow</strong> <strong>hills</strong><strong>Joris</strong> CoolenDepartment <strong>of</strong> Prehistory and Historical Archaeology, University <strong>of</strong> Vienna

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5The Assembly Project – Meeting-places in <strong>No</strong>rthern Europe AD 400-1500 (<strong>TAP</strong>) is aninternational collaborative research project funded by HERA. HERA is a Joint Research Programme(www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, DASTI, ETF, FNR, FWF, HAZU, IRCHSS,MHEST, NWO, RANNIS, RCN, VR and The European Community FP7 2007-2013, under the Socio-Economic Sciences and Humanities Programme.<strong>TAP</strong> was launched in June 2010 and runs for three years. It is led by the Museum <strong>of</strong> CulturalHistory, University <strong>of</strong> Oslo (Dr Frode Iversen) and consists <strong>of</strong> individual projects based at theCentre for <strong>No</strong>rdic Studies (UHI Millennium Institute) at Orkney (Dr Alexandra Sanmark), theDepartment <strong>of</strong> Prehistory and Historical Archaeology, University <strong>of</strong> Vienna (Dr Natascha Mehler)and the Department <strong>of</strong> Archaeology, University <strong>of</strong> Durham (Dr Sarah Semple).website: http://www.khm.uio.no/prosjekter/assembly_project/cover illustration: Prehistoric burial cairn on the Gallow Hill near Huesbreck, Dunrossness, Mainland,

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>Table <strong>of</strong> contentsIntroduction 4Previous research 4Historical background 4Sources 6Methodology 7Discussion <strong>of</strong> the sites 81) Gallow Hill, Huesbreck, Dunrossness, Mainland 82) Golgo, Sandwick, Dunrossness, Mainland 93) Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga, Cunningsburgh, Mainland 104) Gallow Hill, Scalloway, Mainland 115) Gallow Hill, Tingwall, Mainland 136) Gallow Hill, Walls, Mainland 147) Gallow Hill, Brae, Mainland 158) ‘Gulga’, Gluss, <strong>No</strong>rthmavine, Mainland 169) Watch Hill (Gallow Hill), Eshaness, <strong>No</strong>rthmavine, Mainland 1810) Gallows Knowe, Holsigarth, Mid-Yell, Yell 1811) Gallow Hill, Fetlar 1912) Gallow Hill, Unst 2113) Muckle Heog, Baltasound, Unst 2214) ‘Gallow Hill’, Marrister, Whalsay 2415) Wilgi Geos, <strong>No</strong>rth Roe, Mainland 25Comparison <strong>of</strong> the sites 25Gallow <strong>hills</strong> and parish division 27Gallows and prehistoric monuments 33Discussion 34Acknowledgements 36<strong>No</strong>tes 37References 38Appendix IHistorically recorded death penalties and other referencesto execution sites in Shetland 41Appendix II Panoramic photo mosaics 463

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5IntroductionLooking out over Tingwall Loch from theLaw Ting Holm – supposedly the main assemblysite in Shetland from at least the end <strong>of</strong> the13th till the end <strong>of</strong> the 16th century (Coolen& Mehler 2010. Coolen & Mehler 2011. Smith2009) – one <strong>of</strong> the landscape features thatdraws attention is the Gallow Hill (Fig. 1). Theclose spatial and functional connection <strong>of</strong> theancient court site and the supposed <strong>gallow</strong>ssite has long been recognised. Hence, a study<strong>of</strong> Shetland’s assembly sites and their rolein Medieval society should also include theassociated places <strong>of</strong> execution. This <strong>survey</strong>aims to collect the evidence <strong>of</strong> the known oralleged places <strong>of</strong> execution in Shetland (Fig.2) and investigate their topographical setting,especially with respect to presumed assemblysites and parish boundaries.Previous researchThe old <strong>gallow</strong>s sites in Shetland havedrawn the attention and aroused the imagination<strong>of</strong> both local residents and visitorsfor many centuries. In his Description <strong>of</strong> theShetland Islands from the year 1822, SamuelHibbert stated that the Gallow Hill in Yellwas ‘an occasional place <strong>of</strong> execution in thecountry, during the oppressive period whenfeudality exercised its lawless dominion overthe injured udallers’ (Hibbert 1822: 397).He also described another alleged executionsite, known as Hanger Heog, in Unst (see p.22), which he believed to be associated withanother <strong>No</strong>rse assembly site and a pagansanctuary (Hibbert 1822: 403-407). AlthoughHibberts interpretation <strong>of</strong> the site is highlyobjectionable (Smith 2009: 38), he was theirst to explicitly date one <strong>of</strong> Shetland’s executionsites and, moreover, link it to an assemblysite.In 2006, Brian Smith delivered a paperon Shetland’s <strong>gallow</strong>s sites (Smith 2006).The paper dealt with the evidence <strong>of</strong> formerplaces <strong>of</strong> execution found in place names andlocal traditions, and tried to interpret thesesites within a historical and landscape con-Figure 1 View <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill in Tingwall (right)with the Law Ting Holm in the foreground.text. Smith originally counted thirteen sites,and later added a fourteenth on the isle <strong>of</strong>Whalsay 1 . However, he now considers some<strong>of</strong> these sites problematic (pers. comm. 30May 2011). <strong>No</strong>netheless, they will still be discussedin the present <strong>survey</strong>.Smith noted several common features <strong>of</strong>Shetland’s <strong>gallow</strong>s sites: they are all highlyvisible from the surrounding area and can <strong>of</strong>tenonly be accessed via a steep route; prehistoricstructures (mostly cairns) can be foundat most <strong>of</strong> the sites; some <strong>of</strong> the sites areclose to important Medieval settlements, andinally some <strong>of</strong> them are associated with placenames, which refer to old judicial districts.Historical backgroundThe history <strong>of</strong> Shetland’s places <strong>of</strong> executionis <strong>of</strong> course strongly connected with itsjudicial history. For certain places to be setapart as institutionalised places <strong>of</strong> execution,known to and accepted by the local societyand embedded in the collective understanding<strong>of</strong> the landscape, it required a centralauthority, which had the power to both inlictcapital punishment as well as lastingly destinea locale for this purpose. It seems unlikelythat this level <strong>of</strong> authority was reached beforethe <strong>No</strong>rse colonisation at the turn <strong>of</strong> the 9thcentury AD, or even before the annexation <strong>of</strong>the <strong>No</strong>rthern Islands with <strong>No</strong>rway under therule <strong>of</strong> Harald Fairhair in 875 2 .The political and judicial organisation <strong>of</strong>Shetland in the <strong>No</strong>rse period has been the4

Gallow <strong>hills</strong> 1 Gallow Hill, Huesbreck2 Golgo, Sandwick3 Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga, Cunningsburgh4 Gallow Hill, Scalloway5 Gallow Hill, Tingwall6 Gallow Hill, Walls7 Gallow Hill, Brae8 Golga Scord, Gluss9 Watch Hill (Gallow Hill?), Eshaness10 Gallows’ Knowe, Mid Yell11 Gallow Hill, Fetlar12 Gallow Hill, Unst13 Muckle Heog, Unst14 Setter Hill (Gallow Hill?), Whalsay15 Wilgi Geos, <strong>No</strong>rth RoeFigure 2 Map <strong>of</strong> Shetland with the location <strong>of</strong>the discussed sites.topic <strong>of</strong> debate for almost a century (Clouston1914: 429-432. Donaldson 1958: 130-132.Smith 2009. Sanmark, forthcoming). At large,it was probably similar to the organisation inthe Scandinavian mainland and the <strong>No</strong>rse colonies.Hence, Shetland may have been dividedinto several parishes, each <strong>of</strong> which had theirown local thing council. The local things wereprobably subjected to one supreme court,an althing. The latter resided in Tingwall atleast from the late <strong>No</strong>rse period. ThroughoutScandinavia, the althing was the mainlegislative and judicial power, which acted byunrecorded, local laws. However, during thecourse <strong>of</strong> the Middle Ages, the different althingsbecame more and more dependent on theking and his noblemen. At the same time, thejudicial function <strong>of</strong> the things became moreprominent, implementing royal, centrally enforcedlegislation rather than local, unwrittenlaws (Sanmark 2006. Smith 2009: 39).The location <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> Shetland’s thingsites can be deduced form place names (Sanmark,forthcoming). Some scholars believethe thing-sites <strong>of</strong> the <strong>No</strong>rthern Islands to dateback to the ninth century (Fellows-Jensen1996: 26), but Smith has recently argued thatthe known thing-parishes were probably onlyestablished around 1300 (Smith 2009).In general, death penalties, especially byhanging, were rare during the <strong>No</strong>rse period.It was not until the 11th century that the laws<strong>of</strong> the different assemblies in the <strong>No</strong>rwegiankingdom were started to be recorded. Eventhen, most crimes were sentenced with inesor outlawry, while blood vengeance musthave been common practice well into the13th century as well. Although the <strong>No</strong>rselaws did prescribe capital punishment in rarecases, the thing-courts had no central executivepower. In Iceland for example, the althingseems not to have executed death penaltiesbefore 1564 (Bell 2010: 31). At the end <strong>of</strong> the13th century, Shetland’s lawthing adopted thegeneral law issued in 1274 by Magnus Hákonarson,nick-named the Lawmender. Therewere different versions <strong>of</strong> Magnus’ lawbookfor the individual law districts <strong>of</strong> (mainland)<strong>No</strong>rway; Shetland and Orkney adopted theGulathing version, which formed the base <strong>of</strong>the udal law on land ownership still occasionallyinvoked today (Robberstad 1983; Jones1996). The Gulathing law states that a nativethrall, who has committed theft, shall be beheaded(Gulathing 259), but it does not containany other explicit statements on death5

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5penalty. However, several references to thehanging <strong>of</strong> thieves and traitors can be foundin the Heimskringla sagas, recorded around1230 by Snorri Sturluson.From the second half <strong>of</strong> the 13th century, thekings <strong>of</strong> Scotland increasingly gained powerin the <strong>No</strong>rthern Islands. Shetland inally cameunder Scottish rule in 1469, as it was pledgedby Christian I <strong>of</strong> Denmark-<strong>No</strong>rway to JamesIII <strong>of</strong> Scotland for the dowry <strong>of</strong> his daughterMargaret (Crawford 1983). However, it wasnot until 1611 that Scottish law was fullyadopted in Shetland. Until then, judgementsby the lawthing and (later) the sheriff werestill mainly based on the law issued by MagnusLawmender.In 1564, Lord Robert Stewart received a feu<strong>of</strong> Orkney and Shetland from his half-sister,Queen Mary <strong>of</strong> Scotland, and he later acquiredthe earldom and sheriffship <strong>of</strong> both archipelagos(Anderson 1982. Anderson 1996: 179).Robert appointed his half-brother, LaurenceBruce, as sheriff. Soon after Robert Stewartcame into power, the lawthing was movedfrom its traditional site in Tingwall to Scalloway,Shetland’s new capital. After his deathin 1593, Robert was succeeded by his sonPatrick, who commissioned the building <strong>of</strong>Scalloway castle (Anderson 1992). Like hisfather, Patrick used his power to exploit theislands for his own beneit rather recklessly(Donaldson 1958: 10 f.). He was arrestedupon charges <strong>of</strong> treason in 1609 and inallyexecuted in Edinburgh in 1615.From the reign <strong>of</strong> the Stewarts onwards,we get a good view <strong>of</strong> judicial practice inShetland from the preserved court books.They document several executions and otherpunishments, which were carried out at the<strong>gallow</strong>s (Appendix I). The oldest known referenceto <strong>gallow</strong>s in Shetland dates from 1574,and most likely refers to the Gallow Hill inScalloway. Smith (2006) believes that the lastexecution in Shetland took place around 1690(Smith 2006). The folklorist James (‘Jeemsie’)Laurenson has claimed that the last witchwas hanged on Fetlar in 1703, but the historicalrecord mentioned by Laurenson is notknown to me. 3 Most <strong>of</strong> the convicts, who weresentenced to death in the 17th century, werefound guilty <strong>of</strong> thievery; some, however, werecondemned for witchcraft, and there is onecase each <strong>of</strong> murder and bestiality.SourcesThe main evidence <strong>of</strong> former execution sitesin Shetland is found in place names. The nameGallow Hill can be found at least seven times inShetland. Apart from the frequency, the nameis highly remarkable in itself, since more thanninety percent <strong>of</strong> all place names in Shetlandare <strong>of</strong> <strong>No</strong>rse origin and not comprehensible tomodern English speakers (Nicolaisen 1983).Apart from the Gallow Hills, there are fourplace-names, which have been interpretedas derivatives from gálgi, meaning <strong>gallow</strong>s inOld <strong>No</strong>rse.The only place <strong>of</strong> execution in Shetland,for which there is historical evidence, is theGallow Hill in Scalloway. Several executions,which took place here in the early 17th century,are documented in the court books <strong>of</strong>Shetland and Orkney (see Appendix I). Unfortunately,no old maps or scenes that show theexact location <strong>of</strong> these or any other <strong>gallow</strong>s inShetland are known so far.By the time when the documents start tospeak, Scalloway was the seat <strong>of</strong> Shetland’smain court, which dealt with all capital <strong>of</strong>fences.Death penalties were only performedin Scalloway. Assuming that at least some <strong>of</strong>the other alleged <strong>gallow</strong>s sites were indeedused for executions, the lack <strong>of</strong> historical evidencethus provides a terminus ante quem.With one possible exception on Fetlar (seep. 19) none <strong>of</strong> the sites <strong>of</strong>fers any visible,archaeological evidence for the former presence<strong>of</strong> gibbets or <strong>gallow</strong>s. Hence, archaeologyin its traditional sense, as ‘the study <strong>of</strong>past human societies and their environmentsthrough the systematic recovery and analysis<strong>of</strong> material culture or physical remains’ (Darvill2002: 21), cannot help us much furthereither.In some cases, the morbid history <strong>of</strong> thesite is recalled by a local tradition. Althoughthese stories form an interesting part <strong>of</strong> the6

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>site’s biography and a wonderful example <strong>of</strong>the cultural meaning <strong>of</strong> places, we need to beaware that they also have their own culturalbiography and may well have turned up lateror may have signiicantly changed over time.In short, the evidence for the alleged places<strong>of</strong> execution needs to be critically assessedfor each site individually. By comparing thenature <strong>of</strong> the sites and their position in thewider landscape, and compare them to places<strong>of</strong> execution in other regions, we might indsimilarities that could give us some more informationabout the history <strong>of</strong> these intriguingplaces. A Geographical Information System(GIS) provides a valuable tool to analysethe topography <strong>of</strong> the sites and their relationshipboth with the physical environment andthe historic landscape.MethodologyMost <strong>of</strong> the sites, which will be discussedbelow, were visited in May and June 2011 toinvestigate their topography and check forthe presence <strong>of</strong> archaeological features. Onthis occasion, panoramic photos were takenin a 360° angle on every site, using a regularcompact digital camera (Appendix II). Sincethe exact location <strong>of</strong> the <strong>gallow</strong>s is not knownfor any <strong>of</strong> the sites, except (perhaps) the oneon Fetlar, the photos were taken from the spot,which <strong>of</strong>fers the widest view <strong>of</strong> the surroundingarea (and hence also presents the mostvisible spot). The single photos were adjustedand stitched together in Adobe Photoshop.Additionally, a viewshed was created forevery site in ArcMap 10.0. A viewshed modelsthe areas, which are visible from one or severalobservation points, based on a digital terrainmodel (DTM). The accuracy <strong>of</strong> the viewshedhence depends on the spatial resolutionand vertical accuracy <strong>of</strong> the used DTM.The viewsheds presented below werecalculated on the basis <strong>of</strong> the OS LandformPanorama DTM <strong>of</strong> Shetland (excluding FairIsle), freely available from Ordnance Survey. 4It has a horizontal resolution <strong>of</strong> 50x50m andvertical resolution <strong>of</strong> 1m. The OS LandformPanorama DTM was created by interpolation<strong>of</strong> 10m contour lines, derived from the Landranger®1:50,000 scale map series, which inturn were generated from stereo aerial photographyfrom the 1970s (Ordnance Survey2010: 9).It is assumed that the visibility <strong>of</strong> the siteand its surroundings are reciprocal, i.e. thatthe site can be seen from all areas, which arevisible from the site. Since the <strong>gallow</strong>s or gibbetswould have risen to a certain height fromthe ground, the observation points were givenan <strong>of</strong>fset <strong>of</strong> 2m. In some cases, a combinedviewshed was created for several pointsaround the spot from where the photos weretaken, to reduce the effect <strong>of</strong> sharp drops inthe DTM at grid cell edges and to achieve abetter correspondence with the actual view.The viewsheds do not only help to locatethe landscape features shown on the panoramicphotos, but also allow for a quantitativeanalysis <strong>of</strong> the view. We can calculate the size<strong>of</strong> the visible area, and also calculate the division<strong>of</strong> the visible land and sea surface. SinceShetland’s vegetation has hardly changed inthe past 3000 years (Bennett et al. 1992), it<strong>of</strong>fers good opportunities for viewshed analysis;trees being rare, it can be assumed thatthe view across the landscape was almost thesame in the Middle Ages as it is now.7

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5Figure 3 Topography <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill, Huesbreck.The little star marks the viewshed’s observerpoint (see ig. 4). (Data: Ordnance Survey.© Crown copyright /database right 2010).Forra Ness are visible in the distance, with asmall stripe <strong>of</strong> the Atlantic behind them. Thebest land view from Gallow Hill is towards thenorth, where it overlooks almost all the landbetween the observer and the Ward <strong>of</strong> Scousburgh(263 m), located 4.5km to the north. Tothe northeast, one can see the settlements <strong>of</strong>Boddam and Dalsetter. To the east, the Loch<strong>of</strong> Browbreck is visible in the foreground, andwe have a grand view <strong>of</strong> the <strong>No</strong>rth Sea, withthe horizon at a distance <strong>of</strong> c. 30km. However,the coast itself, which is about 850m from thetop <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill, and the voe below Boddamare obscured by the slope.The top <strong>of</strong> the Gallow Hill is marked bya cairn, which was scheduled by HistoricScotland in 1975. 5 It is surrounded by other, Discussion <strong>of</strong> the sites1) Gallow Hill, Huesbreck, Dunrossness,MainlandHU 3929 1443The southernmost Gallow Hill is locatedsouth <strong>of</strong> Boddam (Fig. 3). It is formed by asmall hillock at the east side <strong>of</strong> a larger butgradual hill. The main road A 970 crossesthe hill between the Gallow Hill and theslightly higher ‘summit’ (68 m) to the west<strong>of</strong> the road. Despite its moderate elevation,the Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong>fers a ine view <strong>of</strong> southernDunrossness and can in return be seen from alarge surrounding area (Fig. 4 & 49). The GallowHill overlooks the valley up to the ridge<strong>of</strong> Ward Hill (80 m), about 2km to the south,with the top <strong>of</strong> the Compass <strong>of</strong> Sumburgh justvisible behind it. The West Voe <strong>of</strong> Sumburgh,opening out into the Atlantic Ocean, appearsto the southwest, adjaced by Fitful Head.However, since the land continues to slopeup in this direction for about 350 m, the landlying between the top <strong>of</strong> the hill and the landscapefeatures mentioned before is largelyobscured. To the <strong>No</strong>rthwest, Loch Spiggie and Figure 4 Viewshed from Gallow Hill, Huesbreck.(DTM: Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright/database right 2010).8

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5to the northwest <strong>of</strong> Golgo, around the Stove,are obscured by the gradual hill slope, butone can see the settlements <strong>of</strong> Houlland, Leebittenand Sandwick. To the north, the viewextents to the Ward <strong>of</strong> Veester (257 m) at theborder <strong>of</strong> Cunningsburgh. To the northeast,one can see parts <strong>of</strong> Greenmow and Helliness.The hill overlooks <strong>No</strong> Ness to the (south)east,with Mousa behind it, and <strong>of</strong>fers a wide view<strong>of</strong> the <strong>No</strong>rth Sea <strong>of</strong> almost 150°, the horizonlying again at a distance <strong>of</strong> c. 30km.According to a report by Elizabeth Stout,traces <strong>of</strong> ancient burials were found at Golgoin 1911 (Smith 2006).3) Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga, Cunningsburgh, MainlandHU 4236 2664The Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga is a small, yet remarkableoutcrop knoll on the east slope <strong>of</strong> theWard <strong>of</strong> Veester, on the border between Cunningsburghand Dunrossness (Fig. 7). It liesabout 180m above see level and can only bereached by a steep climb (Fig. 8). Jakobsen(1897: 118 f.) referred to the hill as Wulga,which ‘stands for Gwulga, (…) another form<strong>of</strong> ‘Golga’. This reading <strong>of</strong> the name is supportedby a local tradition, according towhich the notorious sheep thief Kail (or Kil)Hulter was hanged here. A written version <strong>of</strong>the story, published in the Shetland Times inFigure 8 Topography <strong>of</strong> the Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga,Cunningsburgh. (Data: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010).1877 (27 January), sets the story in the early18th century. The story shows many similaritiesto the abundant folk stories dealing withoutlaws from Iceland (Sigurðsson 2006), andis obviously much older. Interestingly, thename <strong>of</strong> Kil Hulter is very similar to that <strong>of</strong>Kit Huntling, known from Orkney (B. Smith,personal communication). The latter hasbeen interpreted as a derivation <strong>of</strong> the Old<strong>No</strong>rse ‘kett-hyndla’ (cat-bitch), an evil, femaledog-cat hybrid, which (just like the Medievaloutlaws) haunted inaccessible, marshy uplandareas, such as the Burn o’ Kithuntlins inthe Birsay Hills on Mainland Orkney (Towrie1996-2011). The igure <strong>of</strong> the ‘ketthontla’ inFigure 7 The Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga (Cunningsburgh)seen from the southeast.Figure 9 Remnants <strong>of</strong> a chambered cairn onthe Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga, overlooking Cunningsburghand Bressay to the northeast.10

Gallow <strong>hills</strong> able quartzite outcrop, known as the WhiteStane <strong>of</strong> the Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga. It is separatedfrom the Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga by a boggy depressionand is not as exposed (and therefore notas visible) as the cairn.Since the Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga is set at a rathersteep slope, the vista covers an angle <strong>of</strong> almost160° towards the east <strong>of</strong> the cairn, whilethe view towards the west is limited by thenearby <strong>hills</strong>ide (Fig. 10 & 51). Although theview from the cairn is quite spectacular, coveringan area <strong>of</strong> almost 3000km², it mainlycovers distant areas, while the closer neighbourhoodis largely obscured.To the north, we can see the hilltops <strong>of</strong> Hoo<strong>Field</strong> on the opposite site <strong>of</strong> the Burn <strong>of</strong> Catpund,the latter being known for its <strong>No</strong>rsesteatite quarry. Catpund itself is obscured bythe slope below the Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga. The site<strong>of</strong>fers a wonderful view <strong>of</strong> Cunningsburgh tothe northeast, extending as far as Bressay andon clear days even to Whalsay. To the southeastwe see Mousa, and turning further in thesame direction we can see the headland <strong>of</strong> <strong>No</strong>Ness. Because <strong>of</strong> the higher elevation <strong>of</strong> theKnowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga, the horizon at the open sealies at c. 50km distance. 4) Gallow Hill, Scalloway, MainlandFigure 10 Viewshed from the Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga,Cunningsburgh. Legend: see ig. 4 (DTM: OrdnanceSurvey. © Crown copyright /database right2010).turn resembles the Icelandic monster Grýla(Jónasdóttir 2010: 21). Hence, both the storyitself and the name <strong>of</strong> its main character seemto be part <strong>of</strong> Shetland’s <strong>No</strong>rse heritage. It isdoubtful, whether the story <strong>of</strong> Kil Hulter hasa kernel <strong>of</strong> truth. However, it is possible, thata common story passed on across the <strong>No</strong>rsecolonies was connected to existing locales,such as the place <strong>of</strong> execution.The Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga is marked by the remnants<strong>of</strong> a large chambered cairn, which wasbuilt on top <strong>of</strong> the natural, rocky hillock (Fig.9). About 120m to the west, there’s a remark-HU 3991 3963The Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Scalloway lies directly tothe west <strong>of</strong> the town (Fig. 11). The site <strong>of</strong> the<strong>gallow</strong>s is described as ‘the west hill <strong>of</strong> Scallowaycallit the <strong>gallow</strong> hill abone Houll’ in thecourt book <strong>of</strong> Shetland in 1615 (Barclay 1967:116). (Wester)Houll was a group <strong>of</strong> houses onthe west side <strong>of</strong> Scalloway, the name <strong>of</strong> whichstill survives in Houl Road. In recordings <strong>of</strong>1616 and 1625 the Gallow Hill is referred toas ‘the place <strong>of</strong> execution’ on the ‘hill aboveBerrie’ (Donaldson 1991: 43 & 124). Berry isa farm on the north side <strong>of</strong> Scalloway, about500m from Houll. Morphologically, the GallowHill is a small spur on the <strong>hills</strong>ide <strong>of</strong> theHill <strong>of</strong> Berry (103 m), at the edge <strong>of</strong> the steepbase towards the town.11

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5Figure 11 Topography <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill, Scalloway.(Data: Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright/database right 2010).According to local residents, there is a lowknoll <strong>of</strong> reddish soil about 100 yards west <strong>of</strong>the television mast on Gallow Hill. 7 The soilappears to be burnt, and local tradition has itthat this was the stake <strong>of</strong> the last witch burnings.8 In an internet forum thread on Shetland’s<strong>gallow</strong>s sites, one user commented thatthe burnt spot may be much younger and mayhave been caused by bonires held during theannual Scalloway Gala until the 1990s. 9 Yet,the spot seems to have been known to localsfor quite a long time. Indeed, the court booksshow that several women, who had been accused<strong>of</strong> witchcraft, were strangled and burntat the Gallow Hill, while the male convictswere usually hanged. The hill to the southwest<strong>of</strong> Scalloway, on the Ness <strong>of</strong> Westshore,is known as Witch’s Hill. The name appearsin J.G. Bartholomew’s Survey Atlas <strong>of</strong> Scotland<strong>of</strong> 1912 10 and the half inch to the milemap <strong>of</strong> Shetland issued in 1926 by the samepublisher. 11Be this as it may, the place on Gallow Hill,which apparently shows traces <strong>of</strong> a majorire, is not particularly visible from Scallowayor the surrounding coastal area. Since we mayassume that visibility was a major factor forthe location <strong>of</strong> the <strong>gallow</strong>s, they may havebeen located closer to the steep drop on the<strong>hills</strong>ide above Scalloway. There is a naturalknoll on this side <strong>of</strong> the hill, which <strong>of</strong>fers anexcellent view <strong>of</strong> the town and the adjacentvalley. The panoramic photo was taken fromhere.The viewshed (Fig. 12) represents the combinedviewsheds from two observer pointsspaced 30m apart to overcome obstructionsat the edges <strong>of</strong> DTM grid cells. The cumulativeviewshed corresponds better to the actualvista shown on the panoramic photograph(Fig. 52).The area, which can be seen from this spot,is much smaller than at the sites discussedbefore. This is mainly due to the fact, that itis not possible to see the open sea from herein any direction, but the visible land surfaceis deinitely smaller too. The view towardsthe west and northwest is largely obscuredby the up-sloping <strong>hills</strong>ide <strong>of</strong> the Hill <strong>of</strong> Berry.Towards the northeast, we see Tingwall Valley,with Veensgarth and Laxirth in the distance.Towards the east, the site overlooksScalloway, with the Hill <strong>of</strong> Easterhoull behindit. The site <strong>of</strong>fers the best vista towards the Figure 12 Viewshed from Gallow Hill, Scalloway.Legend: see ig. 4 (DTM: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010).12

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>south, where we can see parts <strong>of</strong> Trondra,East and West Burra and the west coast <strong>of</strong>southern Mainland, and even Fitful Head inthe far distance.5) Gallow Hill, Tingwall, MainlandHU 4105 4279Figure 13 Topography <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill, Tingwall.(Data: Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright/database right 2010).Figure 14 Outcrop knoll on the summit <strong>of</strong>Gallow Hill, Tingwall. View towards the north.The Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Tingwall is located west<strong>of</strong> Loch Tingwall (Fig. 13). The summit lies atthe edge <strong>of</strong> the moorland behind the farm Kirkasetter.It is formed by a small knoll markedby a cairn (Fig. 14). The summit <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hilllies at slightly over 100m ODN, more than90m above the water level <strong>of</strong> Loch Tingwall.Some interesting structures can be seenabout 400m south <strong>of</strong> the cairn. 12 At HU 40934242, there is a group <strong>of</strong> big stones, whichseems to consist <strong>of</strong> various features (Fig. 15 &16). The major concentration (Fig. 16, A) maybe the remnants <strong>of</strong> a chambered cairn. About15m to the southwest, there is a derelict, rectangularenclosure <strong>of</strong> about 10 x 5m (Fig 16,B). It consists <strong>of</strong> a single row <strong>of</strong> stones and isoriented WNW-ESE. It seems to be open atthe NW side. A local amateur archaeologistreports to have dug two small ‘test pits’ on theinside <strong>of</strong> the enclosure several years ago, andto have found pieces <strong>of</strong> charcoal at six inchesdepth. 13ABCDFigure 15 Remnants <strong>of</strong> a cairn and stonelinedenclosure, possibly <strong>of</strong> prehistoric age,on Gallow Hill, Tingwall. View towards thenortheast.Figure 16 Aerial photograph showing theremnants <strong>of</strong> a cairn (A), enclosure (B), oldield wall (C) and modern clearing for feedingsheep (D) on Gallow Hill, Tingwall. (Photo: ARSF/ NERC, courtesy <strong>of</strong> Alexandra Sanmark / <strong>TAP</strong>.)13

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5 Figure 17 Viewshed from Gallow Hill, Tingwall.Legend: see ig. 4 (DTM: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010).A derelict, NNE-SSW oriented ield wall runspast the burial cairn and the enclosure to theeast (Fig. 16, C). About 50m west <strong>of</strong> this group<strong>of</strong> structures, there is a large, oval enclosuresurrounded by a low, earthen bank (Fig. 16,D). While at irst sight it could be taken for anarchaeological site, it appears to be a clearingmade for feeding sheep some years ago. 14According to Michael Leask <strong>of</strong> Asta, there isa circular enclosure about 200 yards northwest<strong>of</strong> the site mentioned before, which hebelieves might delimit a burial ground associatedwith the <strong>gallow</strong>s. 15 I did not ind theenclosure during my short <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> GallowHill. At the moment, there seems to be littleevidence to support the interpretation <strong>of</strong> aburial site.<strong>No</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> these structures is marked on theOS map or recorded by Historic Scotland, butat least the cairn quite obviously represents aprehistoric monument.The viewshed (Fig. 17) was created bycombining the viewsheds from three differentpoints on the summit <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill, toachieve the closest correspondence to the actualvista from the small cairn on the summit<strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill (Fig. 53).To the north and northeast, the site overlooksTingwall valley, Whiteness and Laxirth.The view reaches as far as Nesting, Whalsayand the Out Skerries, and – according to theviewshed – even to Fetlar, more than 50kmaway. The site <strong>of</strong>fers an excellent view <strong>of</strong> LochTingwall and the Loch <strong>of</strong> Asta and the <strong>hills</strong> atthe opposite side <strong>of</strong> both lakes. Towards thesouth, the view reaches down the valley andClift Sound and includes Scalloway, Trondra,East Burra, the Ness <strong>of</strong> Ireland and FitfulHead in the far distance. Towards the southwestand west, the site overlooks the moorlandbetween Tingwall and Whiteness Voe,with several small lakes. Behind it, one cansee the Scalloway islands, parts <strong>of</strong> Sandsting,Foula and the Atlantic. To the northeast, theview includes the Loch <strong>of</strong> Griesta and reachesas far as Weisdale.6) Gallow Hill, Walls, MainlandHU 2556 5104The Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Walls is located at thehead <strong>of</strong> the Voe <strong>of</strong> Browland, which extendsFigure 18 Topography <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill, Walls.(Data: Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright /database right 2010).14

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>north <strong>of</strong> Gruting Voe, overlooking the Bridge<strong>of</strong> Walls (Fig. 18). Its summit lies at 68m ODN.The area is well-known for its prehistoriclandscape, including the famous site <strong>of</strong> Scord<strong>of</strong> Brouster (Whittle et al. 1986), which is locatedonly 500m north <strong>of</strong> the summit <strong>of</strong> GallowHill. Other prehistoric monuments in theneighbourhood include four scheduled cairnsat the southern summit and slope <strong>of</strong> GallowHill (Historic Scotland, site index nr. 5562). 16There are no indications as to where the<strong>gallow</strong>s may have stood. A cumulative viewshed(Fig. 19) was created for ive points – oneon the summit <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill and one in thecentre <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the four DTM grid cells surroundingthe summit – since the viewshedusing a single observer point on the summitwas found to be very patchy and unlikely torepresent the actual view. As I did not visitthe site, the accuracy <strong>of</strong> the viewshed has notbeen checked.Even with the ive observer points, the viewshedshows the visible area from the summit<strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill to be highly fragmented. Althoughthe view does extend very far in somedirections, it includes only few larger, contiguousareas. The site <strong>of</strong>fers a good view onthe Voe <strong>of</strong> Browland to the southeast, and itis even possible to see parts <strong>of</strong> the west coastand some summits <strong>of</strong> south Mainland. Theview <strong>of</strong> the open sea to the south is largelyobscured by the Ward <strong>of</strong> Culswick and the isle<strong>of</strong> Vaila, but they do leave some small strips inthe view open, where one could get a glimpse<strong>of</strong> the Atlantic. Towards the southwest, wecan see the higher elevated parts <strong>of</strong> Foula. Towardsthe west, the view includes the higher<strong>hills</strong> on the Walls peninsula. One can see RonasHill in <strong>No</strong>rth Roe, located 30km north <strong>of</strong>the observer point; the Button Hills in Deltingappear to the northeast, while to the east, theview extends to Weisdale Hill.0 5 km7) Gallow Hill, Brae, MainlandHU 3774 6810The Gallow Hill at Brae is located east <strong>of</strong> thevillage (Fig. 20). It is part <strong>of</strong> a wider uplandarea with several spurs and summits stretchingfrom Busta Voe in the west to Dales Voe inthe east, the highest <strong>of</strong> which are the Button0 2 kmFigure 19 Viewshed from Gallow Hill, Walls.Legend: see ig. 4 (DTM: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010).Figure 20 Topography <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill, Brae.(Data: Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright /database right 2010).15

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5Hills (252m). The summit <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill liesat slightly over 180m ODN. Again, the onlyindication for the former presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>gallow</strong>sis the name itself. The only thing that givesus a small hint about the possible location <strong>of</strong>the <strong>gallow</strong>s is the Gallow Burn, which has itssource on the slope between Gallow Hill andLadies Hill, and runs down to the west.Archaeological sites around the Gallow Hillinclude a scheduled cairn at the base <strong>of</strong> LadiesHill (Historic Scotland site index nr. 3558)and two scheduled cairns in Burravoe (indexnr. 3469), both sites located c. 1.5km from thesummit <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill. The panoramic photo (Fig. 54) was takenfrom the slope <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill about 600mnorthwest <strong>of</strong> the actual summit (which wasmistaken for the nearby Riding Hill), abovethe source <strong>of</strong> Gallow Burn. The viewshed (Fig.21) represents a cumulative viewshed fromive observation points around the summit,and hence does not entirely correspond to theview on the photo.The view from the summit <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hillmainly extends to the west, the view towardsthe east being largely obscured by the nearby<strong>hills</strong>. Towards the southwest, the view coversmuch <strong>of</strong> Aithsting and the Walls peninsula.Due to the moderate slope at the top <strong>of</strong> thehill, the western <strong>hills</strong>ide is hardly visible fromthe summit (as opposed to the panoramicphotograph, which was taken from the <strong>hills</strong>ide),but it is possible to see the village <strong>of</strong>Brae at the base, as well as Busta Voe andthe eastern part <strong>of</strong> Muckle Roe. Behind MavisGrind, one looks out over St. Magnus Bay, withsome hilltops on Papa Stour being visible tothe WSW. The horizon on the open sea lies atc. 52km distance. Towards the northwest, theview covers the uplands <strong>of</strong> <strong>No</strong>rthmavine, withRonas Hill towering above the rest. Towardsthe north, the view includes Sullom Voe,opening out to Yell Sound.8) ‘Gulga’, Gluss, <strong>No</strong>rthmavine , MainlandHU 3379 7660? Figure 21 Viewshed from Gallow Hill, Brae.Legend: see ig. 4 (DTM: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010).This site was discussed by Brian Smith(2006). Apparently, Da Scord o Gulga is ‘thename <strong>of</strong> a notch in the <strong>hills</strong>ide just south <strong>of</strong>a hill with a cairn on top <strong>of</strong> it’. Smith believedthat the name Gulga might then refer to thehill with the cairn. Jakobsen (1897, 118)mentions a hill called Golga in <strong>No</strong>rthmavine,but unfortunately, he does not give a preciselocation. Neither Golga nor the Scord o Gulgais marked on any edition <strong>of</strong> the OS map andboth names seem to be <strong>of</strong> very local character.However, judging from Smith’s description,Da Scord o Gulga may well be the same as HamaraScord near South Gluss. The hill wouldthen be the one west <strong>of</strong> South Gluss, which16

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>Figure 22 Presumed location <strong>of</strong> the hill Gulganear Gluss, <strong>No</strong>rthmavine (Data: Ordnance Survey.© Crown copyright /database right 2010).is marked as Yamna <strong>Field</strong> on the OS map andwhich indeed has a cairn on top (Fig. 22).Smith admits that the identiication <strong>of</strong> the<strong>gallow</strong>s site at Gluss is highly speculative, andhe now prefers not to include the site in hisstudy <strong>of</strong> Shetland’s places <strong>of</strong> execution (pers.comm., May 30 2011). Yet, for reasons thatwill be discussed below, the site is included inthis study, although the evidence is <strong>of</strong> coursevery weak. Tentatively, a viewshed was createdfor the summit <strong>of</strong> the aforementioned hill,which lies at 162m ODN (Fig. 23). It must besaid that this presents a highly visible site; towardsthe (north)east, one can see the entirewestern coast <strong>of</strong> Yell, a large part <strong>of</strong> Delting,and even the <strong>No</strong>rth Sea beyond, including theSkerries. Towards the south, the view extendsat least to Weisdale; if we are to believe theviewshed, even Fitful Head is visible, locatedmore than 60km to the south. Towards thewest, the site <strong>of</strong>fers a grand view <strong>of</strong> St. MagnusBay, including Papa Stour and Foula. Figure 23 Viewshed from Gulga(Yamna <strong>Field</strong>), Gluss, <strong>No</strong>rthmavine.Legend: see ig. 4(DTM: Ordnance Survey. © Crowncopyright /database right 2010). 17

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 59) Watch Hill (Gallow Hill), Eshaness,<strong>No</strong>rthmavine, MainlandHU 2590 7809?Figure 24 Topography <strong>of</strong> Watch Hill (GallowHill?), Eshaness (Data: Ordnance Survey. © Crowncopyright /database right 2010). Smith mentions a Gallow Hill at Eshaness,located ‘more or less on the boundary withthe rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>No</strong>rthmavine’. The name doesnot appear on any edition <strong>of</strong> the OS map.The Shetland Amenity Trust’s Place NamesProject has mapped the site on Watch Hill, aknoll to the east <strong>of</strong> Braewick (Fig. 24). The top<strong>of</strong> the hill is marked by a circular cairn, possibly<strong>of</strong> Bronze Age date (Historic Scotland siteindex nr. 6150). 17Located 500m from the coast, but at an elevation<strong>of</strong> 106 m, the site <strong>of</strong>fers a splendid view<strong>of</strong> St. Magnus Bay and the Atlantic covering anangle <strong>of</strong> 200° (Fig. 25). The horizon at sea lies40km away. The site overlooks Eshaness tothe west; towards the south, one can see thecoastline <strong>of</strong> south <strong>No</strong>rthmavine, Muckle Roe,West Mainland, Papa Stour and Foula. To thenortheast, one can see Ronas Hill, while to theeast, the view includes several hilltops on Yell.Both the Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Brae and the hilltop atGluss supposedly named Gulga are visiblefrom the top <strong>of</strong> Watch Hill.10) Gallows Knowe, Holsigarth, Mid YellHU 4878 9122? Figure 25 Viewshed from Watch Hill (GallowHill?), Eshaness. Legend: see ig. 4(DTM: Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright /database right 2010).Smith (2006) mentioned a site called GallowsKnowe at Holsigarth (spelled Halsagarthon OS maps), a deserted cr<strong>of</strong>t opposite the infamousWindhouse near Mid Yell (Fig. 26). Herefers to a tradition recorded by the folkloristLaurence Williamson. According to this story,two men, who were found guilty <strong>of</strong> stealingcattle belonging to the lord <strong>of</strong> WindhouseCharles Neven, were hanged at the GallowsKnowe in the early 18th century. As Smithpoints out, it is very unlikely that an executiontook place at this site as late as the 18thcentury, but he believes the story may have amore ancient origin. Although this is admittedlya daring thought, it is remarkable thatthe Windhouse, known as the ‘most haunted18

Gallow <strong>hills</strong> Figure 26 Topography <strong>of</strong> the Hill <strong>of</strong> Halsagarth,Mid Yell, with the approximate location<strong>of</strong> Gallows Knowe (Data: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010). house’ in Shetland (and beyond), is associatedwith a place <strong>of</strong> execution in a local tradition.In this case, the reputation <strong>of</strong> the house mayhave inspired the story, but it could also bethe other way round; similar to the reservationagainst the last inhabitant <strong>of</strong> Golgo, thenegative connotation <strong>of</strong> Windhouse may beolder than the house itself and originate froman older, fearful place.Be this as it may, the name <strong>of</strong> the GallowsKnowe is neither marked on any historicalor modern map, nor is it generally known tolocal residents. Smith now considers the evidencefor this site too weak and prefers not toinclude it in his study <strong>of</strong> <strong>gallow</strong>s sites anymore(pers. comm., May 30 2011). Due to thepoor localisation <strong>of</strong> the site, little can be saidabout its visibility. Tentatively, a viewshedwas calculated for the spot on the northernslope <strong>of</strong> the Hill <strong>of</strong> Halsagarth (Fig. 27), wherethe panoramic photos were taken (Fig. 55). Itmust at least be close to the alleged GallowsKnowe. Compared to the other sites, the visibilityappears rather limited. However, theview includes both Whale Firth in the westand (parts <strong>of</strong>) Mid Yell Voe in the east.Figure 27 Viewshed from the Hill <strong>of</strong> Halsagarth(approxiamte location <strong>of</strong> Gallows Knowe), MidYell. Legend: see ig. 4 (DTM: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010).11) Gallow Hill, FetlarHU 5919 9070The Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Fetlar is located at thewest side <strong>of</strong> the island. It is a large hill withgradual slopes on all sides, except for the west,where it has steep cliffs to Colgrave Sound(Fig. 28). Its summit lies at 106m ODN.The Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Fetlar is the only placeknown in Shetland, where possible remains<strong>of</strong> the execution site can still be seen today.About 750m SSW <strong>of</strong> the television mast and200m from the coast, there is a knoll with aremarkable enclosure on it (Fig. 29). The enclosureis formed by a low turf wall (thougha stone wall might be buried beneath) up to40cm high and about 1m wide at the base(Fig. 30). It is slightly trapezoidal; the side19

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5Figure 28 Topography <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill, Fetlar.The star marks the location <strong>of</strong> the square enclosure(Data: Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright/database right 2010).Figure 29 The enclosure on Gallow Hill, Fetlar,set on top <strong>of</strong> a natural low mound. Viewtowards the south.Figure 30 Earthen bank on the east side <strong>of</strong> thesquare enclosure on Gallow Hill, Fetlar. Viewtowards the north.lengths are 22-24m on the north, west andeast sides, while the south side measures c.29m. The bank is highest on the north side,which is also the highest part <strong>of</strong> the terrain,while at the deepest spot, in the south, it canonly be vaguely recognised. Smith (2006)mentions a possible gate on the east side, butthis was neither observed in the ield, nor canit be seen on the satellite imagery shown onGoogle Earth 18 (Fig. 31). Apart from the enclosure,the satellite photos clearly reveal traces<strong>of</strong> peat extraction along the coast on the westside <strong>of</strong> the enclosure.The enclosure is marked on the irst edition<strong>of</strong> the OS County Series 1:10,560 (Sheet XVII),issued in 1882, as an old (!) sheepfold. 19 AsSmith pointed out to me, there are several reasonswhy this is an unlikely interpretation. 20In Shetland, sheepfolds were usually roundor oval shaped and located on the shoulder <strong>of</strong>a hill, along hill-dykes, or at the coast, whereit would be easier to collect the sheep. Sincethe enclosure on Gallow Hill lies in open terrain,it would be very hard to drive sheep intoit, unless it had lead-fences associated withit. Moreover, the enclosure would be exceptionallylarge for a regular sheepfold. Finally,there is a strong local tradition that the siterepresents an old execution place, which wasirst recorded by T.A. Robertson and J.J. Grahamin 1964 (p. 51), quoting the folklorist J.Laurenson. They stated that ‘the hole in theGallow Hill where the <strong>gallow</strong>s stood can stillbe seen’. Indeed, there is a hole more or less inthe centre <strong>of</strong> the enclosure, with at least onestone visible at the side. However, Laurensonrecalled that the stones, which used to line thepit on Gallow Hill, were removed by some boyshunting rabbits. 21 Laurenson also mentionedtwo stones at both sides <strong>of</strong> the executionsite, on which according to the tradition thejudges sat during the witch trials. 22 However,there are no visible large stones on or nearthe enclosure today. According to Laurenson,the last witch executed on Fetlar in 1703, butthis date seems not to be conirmed by anywritten evidence. Laurenson also stated thathanging was the usual punishment for witcheson Fetlar, as opposed to Scalloway, where20

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5top <strong>of</strong> the hill forms a plateau. The actual summitis not very distinctive, but it is marked byan OS benchmark. It lies at 99m ODN, betweentwo small ponds. The benchmark standswithin an interesting structure, recorded bythe RCAHMS as site number HP50SE 23 (Fig.34). 25 It comprises several small and larger,partly interconnected circular drystone walls.According to the RCAHMS database, this isa look-out shelter, built from the stones <strong>of</strong> avery large cairn. The cairn was subject to severalexcavations in the 19th century. As theirst edition <strong>of</strong> the OS Country Map series 1:10,560 notes, stone cists were found here in1825, apparently containing several humanskulls. Fourty years later, the site was excavatedby James Hunt (Smith 2011), who foundthe remains <strong>of</strong> a human skeleton with somelimpet shells (Hunt 1866, 297). About 100mto the south, there is another cairn, which apparentlyalso yielded stone cists in 1825. Nextto it is an old sheepfold known as the Pund<strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill. On the southern <strong>hills</strong>ide, 650msouthwest <strong>of</strong> the summit, there is a large,heel-shaped chambered cairn scheduled byHistoric Scotland (index nr. 7667). 26The panoramic photo was taken from the OSbenchmark at the summit <strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill (Fig.57). A cumulative viewshed was calculatedfor the summit and four additional points atthe corners <strong>of</strong> the respective DTM grid cell(Fig. 35). The site <strong>of</strong>fers an excellent view <strong>of</strong>Colgrave Sound and the surrounding islands,including Uyea, Fetlar, Hascosay and Yell. Theeast coast <strong>of</strong> Yell is almost entirely visible.The view reaches as far as Whalsay or even<strong>No</strong>rth Nesting to the south and Ronas Hill tothe west and across Unst to the north. The site<strong>of</strong>fers a view <strong>of</strong> the open sea to the northwest,east and south, the horizon lying at a distance<strong>of</strong> 40km.Figure 34 Remnants <strong>of</strong> a prehistoric burialcairn on Gallow Hill, Unst, apparently reusedas an outlook shelter and destroyed by earlyexcavation . 13) Muckle Heog, Baltasound, UnstHP 6315 1081 Muckle Heog is a knoll on the east side <strong>of</strong>a chain <strong>of</strong> <strong>hills</strong> between Baltasound and Haroldswick(Fig. 36). Its summit lies at 140mFigure 35 Viewshed from Gallow Hill, Unst.Legend: see ig. 4 (DTM: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010).22

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>Figure 36 Topography <strong>of</strong> Muckle Heog, Baltasound,Unst. (Data: Ordnance Survey. © Crowncopyright /database right 2010).ODN. Although Smith (pers. comm., May 302011) is now sceptical about this site, severalsources recount the tradition that this sitewas used as a place <strong>of</strong> execution.In 1774, George Low wrote about a sitecalled Hanger Heog. He was shown a ‘heap<strong>of</strong> stones’ on the top, which was ‘called bytradition a place <strong>of</strong> execution’ (Low 1879).At the foot <strong>of</strong> the hill was another stone heap,‘called the House <strong>of</strong> Justice, from which oneascends by steps to the former. Tradition says,that whatever criminal ascended the steps <strong>of</strong>Hanger Heog never came down alive’. The sitepresented a key site for the reconstruction<strong>of</strong> the ancient judicial system in Shetland toSamuel Hibbert in 1822 (p. 406). His accountseems to be based on Low’s, since he usesvery similar words. He adds that ‘in conirmation<strong>of</strong> the account, two bodies, supposedto have been executed criminals, were, aboutsixty years ago, found buried in disorder nearthe base <strong>of</strong> the lower heap <strong>of</strong> stones’. Surprisingly,Hibbert (1822: 269) interprets the siteas a Scandinavian temple elsewhere, erectedby the irst <strong>No</strong>rse settlers upon their arrivalin Haroldswick. He also believed the place<strong>of</strong> execution on Hanger Heog was associatedwith what he interpreted as an assembly sitemarked by three concentric circles at Crussa<strong>Field</strong>, about 1.5km to the west (Hibbert 1822:405 f.). 27 Between the alleged assembly siteand the place <strong>of</strong> execution there was anothersimilar monument, which according toHibbert was a sanctuary, to which a convict Figure 37 Viewshedfrom Muckle Heog, Unst.Legend: see ig. 4 (DTM:Ordnance Survey. © Crowncopyright /database right2010).23

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5could try to escape after his trial; if he managedto reach it safely, his life was preserved,but anybody was free to pursue and kill himon his way there. There is a similar story inTingwall, featuring either the steeple <strong>of</strong> TingwallKirk (Brand 1701 [1883]: 184) or the socalled Murder Stone at Asta (Fojut 2006: 116)as the sanctuary, to which a convict could tryto lee.All structures on the <strong>hills</strong> north <strong>of</strong> Baltasoundthat were mentioned by Low andHibbert are in fact prehistoric burial cairns.Some <strong>of</strong> them were excavated by J. Hunt andR. Tate in 1865 (Hunt 1866. Tate 1866), afteran initial ind <strong>of</strong> human remains and soapstonevessels on the Muckle Heog the previousyear (Roberts 1865) had awakened theirinterest. Tate (1866: 342) also mentions thetradition <strong>of</strong> the place <strong>of</strong> execution in his report,which allows us to identify Hanger Heogas the Muckle Heog.As Smith (2009: 38) rightly states, ‘everystep in Hibbert’s reconstruction is fantasy’.Both Hibbert’s and Tate’s accounts seem toheavily rely on Low’s, and neither <strong>of</strong> themcites any contemporary source to conirm thetradition. There is no archaeological evidenceto support the tradition, at least if we do notattach too much value to Hibbert’s interpretation<strong>of</strong> the human remains from the so calledHouse <strong>of</strong> Justice. Of course it needs to bequestioned if the laymen, who had excavatedthe cairns at Muckle Heog and the House <strong>of</strong>Justice even before Tate’s expedition, wouldhave noticed any difference between Medieval,deviant burials and a prehistoric communalgrave. Finally, the place name HangerHeog is suspicious too and might refer to asteep, overhanging hill rather than a <strong>gallow</strong>ssite (Smith 2006). However, given the traditionand the location <strong>of</strong> the site, it should notbe altogether dismissed as a possible place <strong>of</strong>execution.The viewshed represents a cumulativeviewshed <strong>of</strong> the summit <strong>of</strong> Muckle Heog andone point in each <strong>of</strong> the four adjacent gridcells <strong>of</strong> the DTM (Fig. 37). The site <strong>of</strong>fers agood view <strong>of</strong> Unst both towards the north andsouth, including Balta Sound, Haroldswickand Hermaness. The southern part <strong>of</strong> Unstis largely obstructed by the Hill <strong>of</strong> Caldwickand Valla <strong>Field</strong>, but interestingly, the summit<strong>of</strong> Gallow Hill is visible. Towards the south,the view includes the northern coast <strong>of</strong> Fetlar,as well as the summit <strong>of</strong> Fetlar’s Gallow Hill.Towards the southwest, the view reaches tosome hilltops on Yell and Mainland. The opensea can be seen towards the (south)east,west, north and northeast; the horizon lies c.45km away.14) ‘Gallow Hill’, Marrister, WhalsayHU 5480 6388?As Smith reported in an internet forum 28 ,he was informed about another Gallow Hill atMarrister on Whalsay after his lecture in 2006.However, the name is not marked on any mapand could so far not be veriied. Perhaps it isanother name for Setter Hill, since this is theonly distinct hill near Marrister (Fig. 38). Thesite was mapped, but the evidence is consideredtoo weak to attempt further analysis (includinga viewshed), as long as the name andlocation <strong>of</strong> the site are not conirmed.Figure 38 Topography <strong>of</strong> Setter Hill (GallowHill?), Whalsay. (Data: Ordnance Survey. ©Crown copyright /database right 2010).24

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>Wilgi Geos should probably not be includedin the list <strong>of</strong> <strong>gallow</strong>s sites in Shetland. It waslisted for completeness, but was not includedin the following analysis.Comparison <strong>of</strong> the sitesFigure 39 Topography <strong>of</strong> the Wilgi Geos, <strong>No</strong>rthRoe. (Data: Ordnance Survey. © Crown copyright/database right 2010).15) Wilgi Geos, <strong>No</strong>rth Roe, MainlandHU 3444 9163The Wilgi Geos is an inlet at the northerncoast <strong>of</strong> <strong>No</strong>rth Roe (Fig. 39). It has been suggested,that the name Wilgi Geos (very similarto the Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga in Cunningsburgh)might also be derived from Old <strong>No</strong>rse gálgi.The Wilgi Geos is a remote place, and notparticularly visible. Although boats mightpass entering or leaving Sand Voe, the <strong>gallow</strong>swould not have been visible unless they wereplaced at the head <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the neighbouringpromontories, or indeed higher up the hill. Inthis case, it would be surprising that the inletinstead <strong>of</strong> the promontory was named afterthe <strong>gallow</strong>s.The site is located 3km from the pre-ReformationSt. Magnus church in Houll, which,as we shall see, does constitute a commoncharacteristic <strong>of</strong> Shetland’s <strong>gallow</strong>s. However,there would have been more suitable placesfor this gruesome purpose closer to the settlementat Houll.Apart from the name, nothing indicates,that the site was used as a place <strong>of</strong> execution.Even if the name derives from gálgi, it may benamed after an overhanging rock. I agree withSmith (pers. comm., 6 June 2011) that theAlthough Smith (2006) highlighted the highvisibility <strong>of</strong> all the <strong>gallow</strong>s sites, a comparison<strong>of</strong> the viewsheds shows that there are in factlarge differences. The total area, which can beseen from each site, varies from less than 40to almost 3,000km² (Fig. 40). The most visiblesite is the Knowe o Wilga, while – surprisinglyperhaps – the Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Scalloway isleast visible.The huge difference in the visible area ismainly caused by the visibility <strong>of</strong> the opensea. The sea can be seen from all sites, and inall cases sea surfaces account for more thanhalf <strong>of</strong> the visible area; in 10 out <strong>of</strong> 12 cases, iteven accounts for more than 90 % <strong>of</strong> the visiblearea. The total land surface visible fromeach site varies from 16 to 134km². Again, theGallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Scalloway has the lowest score,but the ranking <strong>of</strong> the other sites is completelydifferent. The dubious site <strong>of</strong> Gluss overlooksthe largest land surface, followed by the GallowHills <strong>of</strong> Brae and Fetlar.However, these numbers are somewhatmisleading; since the area, which is coveredby a certain angle, gets larger with increasingdistance, even a small strip <strong>of</strong> the sea visibleat the horizon represents a huge area. Moreover,due to the curvature <strong>of</strong> the earth, thedistance to the horizon is much larger fromhigher elevated points than from a point closeto sea level. This again leads to an exponentialincrease <strong>of</strong> the visible area towards the horizonfor higher elevated sites.Although it is amazing just how far one cansee from most sites, it is <strong>of</strong> course unrealisticthat the <strong>gallow</strong>s would have been visible from40km distance; even though the site itselfmay have been visible, the <strong>gallow</strong>s and theirinvoluntary companions were much too smallto be seen with the naked eye. Hence, it wouldbe interesting to analyse the visibility <strong>of</strong> the25

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5direct surroundings, since this may indicateif the sites were potentially meant to be seenfrom afar and may hence have a more symboliccharacter, or if they would have been effectivelocations to impress the local passers-by.Although we do not know what the <strong>gallow</strong>sin Shetland may have looked like, they areunlikely to have been monumental enoughto be clearly discernible from more than 3kmdistance. Hence, the total visible area andthe visible land and sea surface within a radius<strong>of</strong> 3km were calculated for each site (Fig.41). This corresponds to a maximum area <strong>of</strong>28.3km². It must be stressed that the inaccuracy<strong>of</strong> the viewshed caused by the resolution<strong>of</strong> the DTM plays a larger role at this scale.The total visible area within 3km from eachsite varies from 17.3 to 6.6km². The largestarea can be seen from Muckle Heog in Unst,while the Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Brae has the mostlimited view <strong>of</strong> the surrounding area. Again,Scalloway is at the bottom <strong>of</strong> the list, directlyafter Brae, the visible area covering 6.9km².The viewshed analysis within a limitedcircle gives a clearer impression <strong>of</strong> the importance<strong>of</strong> the visibility from the sea. The visiblesea surface (including inlets) in the directsurroundings varies greatly. From the GallowHill <strong>of</strong> Tingwall, the sea cannot be spottedwithin a radius <strong>of</strong> 3km at all. On the opposite,the sea represents 70 % <strong>of</strong> the area visiblewithin this circle from the Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilga.Putting it the other way round, there are onlyfour sites, which are more widely visible fromthe sea in the direct surroundings than fromland. These are the Knowe o Wilga, the GallowHills <strong>of</strong> Fetlar and Unst and the Watch Hill in<strong>No</strong>rthmavine.Summarising the above results, we can concludethat the <strong>gallow</strong>s sites were potentiallyhighly visible indeed (taking into account thatwe do not know the exact spot <strong>of</strong> any <strong>of</strong> the <strong>gallow</strong>s,except perhaps those <strong>of</strong> Fetlar, and thatthe above results are a best-case scenario).More importantly, most locations seem not tohave been chosen to be primarily visible forthe advancing sailors, but rather seem to forma compromise: while being visible from afar Figure 40 Diagram <strong>of</strong> the total land and seaarea visible from the discussed sites. The doubtfuland poorly localised sites in Mid-Yell andWhalsay are not included in the diagram. Figure 41 Diagram <strong>of</strong> the total visible landand sea area within a radius <strong>of</strong> 3km fromthe discussed sites. The doubtful and poorlylocalised site in Mid-Yell is not included in thediagram.26

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>both from the sea and land, they must haveformed a very confronting sight to the peoplemoving about the surrounding land. In Scalloway,wide visibility <strong>of</strong> the <strong>gallow</strong>s seems notto have been a major concern at all; however,they may have been perfectly visible from thetown, the castle and the harbour.Gallow <strong>hills</strong> and parish division The parish division in the late 16th andearly 17th century can be reconstructed onthe basis <strong>of</strong> the report on the complaints <strong>of</strong>the commons and inhabitants <strong>of</strong> Shetland<strong>of</strong> 1576 (Balfour 1854: 13-92), the courtbooks (Barclay 1962. Barclay 1967. Donaldson1954. Donaldson 1991), and a list <strong>of</strong>ecclestical ‘beneices’ in Shetland written byRev. James Pitcairn between 1579 and 1612(Goudie 1904: 155-158). The latter showsthat the parishes formed both administrativeand ecclestical units and corresponds tothe description <strong>of</strong> the different (ecclestical)parishes given by John Brand in 1701 (p. 125-146).Most parishes, which appear in thesedocuments, comprise several communitiesor isles. Since the districts are not alwaysgrouped the same way, the total number <strong>of</strong>parishes ranges from nine to thirteen. However,the districts are essentially the same andlargely corresponded to the present parishesin Shetland.In general, we can reconstruct at least tenparishes:- Nesting, Lunnasting, Whalsay and Skerries.The Skerries are listed together withFetlar, Unst and Yell in 1576.- Fetlar- Unst- Yell- <strong>No</strong>rthmavine- Delting. In 1576, it is listed as Delting andScatsta.- Walls, Sandness, Aithsting and Sandsting.Walls is listed separately in 1576 and inPitcairn’s list <strong>of</strong> ecclestical parishes. It alsoincluded Papa Stour. Figure 42 Judicial districts (parishes) in Shetlandaround 1600 with the location <strong>of</strong> <strong>gallow</strong><strong>hills</strong> and other possible <strong>gallow</strong>s sites.Parishes: 1 Dunrossness; 2 Burra & Gulberwick; 3Tingwall, Whiteness, Weisdale & Bressay; 4 Walls,Aithsting & Sandsting; 5 Nesting, Lunnasting &Whalsay; 6 Delting; 7 <strong>No</strong>rthmavine; 8 Yell; 9 Fetlar;10 Unst.- Burra and Gulberwick. The parish also includedQuarff and Trondra, but these are notalways mentioned. In 1603, the parish wasgrouped together with Tingwall, Whiteness,Weisdale and Bressay, in 1604 with Bressayonly.- Dunrossness- Tingwall, Whiteness, Weisdale and Bressay.Bressay is listed separately in 1576,while it is grouped together with Burra inPitcairn’s list <strong>of</strong> ecclestical parishes and in thecourt book <strong>of</strong> 1604.27

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5There is a remarkable correspondencebetween the distribution <strong>of</strong> the <strong>gallow</strong>s andthe parish division listed above. Apart fromthe smallest parish <strong>of</strong> Burra and Gulberwick(also including Quarff), each <strong>of</strong> the parisheshas at least one alleged <strong>gallow</strong>s site (Fig. 42).Interestingly, there is only one site namedGallow Hill in each <strong>of</strong> them, except for Yell,which has none, and Tingwall, which has two.The Gallow Hills <strong>of</strong> Scalloway and Tingwallwere probably not used at the same time; theformer was probably taken into use after thelawthing was moved from Tingwall to Scallowayin the late 16th century and can hencebe considered as the successor <strong>of</strong> Tingwall’sGallow Hill (Smith 2006). It is also strikingthat most <strong>of</strong> the sites lie in the interior <strong>of</strong> theparishes. This is most obvious for the sites insouth and west Mainland and the more dubioussites in <strong>No</strong>rthmavine and Yell. The GallowHills <strong>of</strong> Unst and Fetlar are the only exceptions,since they are both located at the westcoast<strong>of</strong> the islands, facing the neighbouringislands (and parishes). This also applies to thealleged Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Whalsay, but as we haveseen this island did not constitute a separateparish. Indeed, it is surprising, that there isno Gallow Hill in the parishes <strong>of</strong> Nesting andLunnasting, but one on Whalsay instead.The Gallow Hill <strong>of</strong> Brae is a bit harder tojudge: it is located very centrally, but alsooverlooks the border <strong>of</strong> <strong>No</strong>rthmavine.Apart from Scalloway, there is no obviousrelation between the <strong>gallow</strong>s sites and thevenues <strong>of</strong> the local courts held in the early17th century (Donaldson 1958: 133-136)(Fig. 43). Some <strong>of</strong> the <strong>gallow</strong>s sites are relativelyclose to a court site, as in Unst (2.3km)and Delting (2.9km), but most <strong>of</strong> them arenot. This is hardly surprising, since the localcourts probably did not have the power to in-lict capital punishment. Although the districtcourts were presided over by the same judgeas the main court in Scalloway, there seem tohave been different levels <strong>of</strong> judicial power, asin most <strong>of</strong> Europe at this time. Capital crimeswere only brought before the Lawthing orhead court in Scalloway. The Court Books <strong>of</strong> Shetland only document one case, in whichthe convict was sentenced to death by a districtcourt. This concerns the case againstChristopher Johnston from Scatstay, whowas convicted <strong>of</strong> repeated theft by the court<strong>of</strong> Delting at Wethersta in 1602 (Donaldson1954: 18 f.). As far as I know, this is also theearliest known death sentence in Shetland. Instandard wording, Johnston was sentenced‘to be taine to the <strong>gallow</strong> hill and thair to behangeit be the crage quhill he die, in exempill Figure 43 Location <strong>of</strong> court sites mentionedin the courtbooks between 1600 and 1615 withthe location <strong>of</strong> <strong>gallow</strong> <strong>hills</strong> and other possible<strong>gallow</strong>s sites. The parishes correspond to ig.42.Court sites: 1 Neap; 2 Gardie; 3 Still; 4 Ueyasound;5 Islesburgh; 6 Aywick (Eawik); 7 Wethersta (Woddirsta); 8 Twatt; 9 Houss; 10 Sumburgh (Soundbrughe);11 Scalloway; 12 Graveland; 13 Burravoe;14 Brough; 15 Skeldvoe; 16 Sand; 17 Ustaness; 18Hillswick; 19 Urairth.28

Gallow <strong>hills</strong>Figure 44 Location <strong>of</strong> pre-reformation parishchurches (after Cant 1975) <strong>gallow</strong> <strong>hills</strong> andother possible <strong>gallow</strong>s sites.Parish churches: 1 St. Matthew / Cross Kirk,Quendale; 2 St. Magnus?, Sandwick; 3 St. Colme?,Cunningsburgh; 4 St. Olaf, Gunnista; 5 unknown,West-Burra; 6 St. Magnus, Tingwall; 7 St. Mary?,Weisdale; 8 St. Mary, Sand; 9 unknown, Twatt; 10St. Paul, Kirkigarth; 11 St. Margaret, Sandness; 12St. Olaf, Olnairth; 13 St. Magnus, Laxobigging; 14St. Magnus / St. Gregory?, Hillswick; 15 St. Magnus?,Houll; 16 St. Olaf, Ollaberry; 17 St. John, Reairth;18 St. Olaf, Breckon; 19 St. Magnus, Hamnavoe; 20St. Mary, Haroldswick; 21 St. John, Baliasta; 22 St.Olaf, Lundawick; 23 Cross Kirk, Papil; 24 St. Olaf,Kirkabister; 25 St. Margaret, Lunna; 26 Cross Kirk,Kirkness; 27 St. Olaf, Whiteness.<strong>of</strong> utheris’. Unfortunately, the text does notreveal if this refers to the Gallow Hill in Brae(overlooking Wethersta) or to the one in Scalloway.The local courts <strong>of</strong> the early 17th centurywere usually held at the manors <strong>of</strong> the fouds(bailiffs) or other <strong>of</strong>icials. Although most <strong>of</strong>the manors were located in or nearby a majorsettlement, they do not necessarily representthe old centre <strong>of</strong> their parish (Smith 2009:43). Since it has been assumed that Shetland’s<strong>gallow</strong>s sites are indeed older, we need to lookfor other possible associations.The old parish churches may give a betterclue in this respect. Indeed, there is a strikingcorrelation between the <strong>gallow</strong>s sitesand the location <strong>of</strong> the pre-Reformation parishchurches listed by Cant (1975) (Fig. 44).The distance varies from 550m (Sandwick)to 5.2km (Brae); 10 <strong>of</strong> all 14 sites are locatedless than 3km from a Medieval parish church.This applies both to the Gallow Hills as wellas the gulga-names. The most striking examplefor this is Dunrossness. The Gallow Hill<strong>of</strong> Huesbreck lies 2.5km from St. Matthew’schurch (Cross Kirk) in Quendale, which wasabandoned in 1790. 29 The Knowe <strong>of</strong> Wilgalies 1.5km from St. Columba’s church in Mail(Cunningsburgh), while Golga lies only 550mfrom the old parish church <strong>of</strong> Sandwick. 30 Thestrong link between the <strong>gallow</strong>s sites and thepre-Reformation parish churches seems toconirm that the latter hold valuable informa- tion on the old administrative (and judicial)division <strong>of</strong> Shetland. Cant (1996: 166) statesthat Shetland Medieval, ecclestical parishescorresponded with thing-parishes and weregenerally divided into thirds, each with achurch, one <strong>of</strong> them being the main parishchurch.As said before, few documents present aclue to the administrative units before thereign <strong>of</strong> the Stewarts. Based on the number<strong>of</strong> original parish churches in each <strong>of</strong> the districtsmentioned by Pitcairn, Clouston (1914:430 f.) drew a parallel between the parish division<strong>of</strong> Iceland, Orkney, the Isle <strong>of</strong> Man andShetland. This administrative model generallyinvolved a division into quarters and thirds atmultiple levels. According to Clouston, thisapparently typical <strong>No</strong>rse administrative systemhad its origins in the organisation <strong>of</strong> theScandinavian homelands <strong>of</strong> the settlers, goingback to the Germanic Iron Age. Hence, he be-29

<strong>TAP</strong> <strong>Field</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5lieved Shetland’s parishes to be ‘very, very oldindeed’ (Clouston 1914: 432).The thing-element in the name <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong>the parishes indicates a <strong>No</strong>rse origin. It hasbeen noted before that the thing-parishesare all located in the central part <strong>of</strong> Mainland,which lacks clear geographical boundaries(Donaldson 1958: 130. Smith 2009: 41 f.). Tothe names still used today (Delting, Nesting,Lunnasting, Aithsting, Sandsting, Tingwall),two more names can be added, which appearin a document <strong>of</strong> 1321: Þvæitaþing andRauðarþing. The former may have been locatedin the west <strong>of</strong> Shetland, possibly in thepresent parish <strong>of</strong> Walls, while the latter mayhave been in, or even correspond to <strong>No</strong>rthmavine(Jakobsen 1897: 102. Smith 2009: 42).The name Neipnating, recorded in the early16th century and in 1628, probably refers toNesting (Smith 2009: 41).Smith (2009: 42) points out that there areno thing-parishes in Orkney, and that Shetland’sparish things may hence have beenformed around 1300, after Shetland’s separationfrom the Earldom <strong>of</strong> Orkney. He doesagree, though, that Shetland may once havehad the same, symmetrical division into quarters,eighths and thirds known from <strong>No</strong>rway.The former division <strong>of</strong> Fetlar into three smalldistricts was still recalled by a local lady at theend <strong>of</strong> the 19th century (Jakobsen 1897: 117),although it must have been outdated for manycenturies by then. A <strong>No</strong>rwegian document <strong>of</strong>1490 mentions the districts Vogaiordwngh(‘the quarter <strong>of</strong> the voes’) in the west andMawedes otting (‘the eighth at the narrowisthmus’) in the north <strong>of</strong> Shetland (Smith2009: 43). Although the names themselvescan be identiied as Walls and <strong>No</strong>rthmavine– parishes still existing today – Smith stressesthat the parish division and borders may stillhave been very different.Another recurring name, which refers toan older judicial system, is the ‘Herra’ (fromOld <strong>No</strong>rse hérað, meaning county or disrict)(Jakobsen 1897: 117. Smith 2006. Smith2009: 43). The name occurs four times inShetland: in Yell, Fetlar, Lunnasting and Tingwall.The Herra in Yell now refers to a small Figure 45 Location <strong>of</strong> ‘ting-’ and ‘herra’-placenames and <strong>gallow</strong> <strong>hills</strong> (see ig. 44 for legend).Marked sites: 1 Tingwall; 2 Sand; 3 Aith; 4 Neap; 5Lunna; 6 Dale; 7 Herra, Lunnasting; 8 Herra, Fetlar;9 Herra, Yell.area on the west side <strong>of</strong> Whale Firth. It wasformerly called the ‘Oot Herra’, as opposed tothe ‘In Herra’, which lay at the opposite side<strong>of</strong> Whale Firth. The Herra in Fetlar refers tothe settlement area to the north and east <strong>of</strong>Papil Water. Again, the area is divided intoan Upper Herra and the Lower Herra, eachincluding a few farmsteads and located about1km apart. The Herra in Lunnasting lies at thesouth end <strong>of</strong> Vidlin Voe, between the villagesVidlin, Gillsbreck and Orgill. In Tingwall, thename appears in a slightly different form: thearea to the north and west <strong>of</strong> Tingwall Lochis referred to as the Harray in a document <strong>of</strong>1525 (Stewart 1987: 130). The name survives30