St Martins Marsh Aquatic Preserve

16gt4Qnop

16gt4Qnop

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong><br />

<strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong><br />

Management Plan<br />

<strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong><br />

3266 North Sailboat Avenue<br />

Crystal River, FL 34428<br />

352.228.6028 • www.dep.state.fl.us/coastal/sites/stmartins<br />

Florida Department of Environmental Protection<br />

Florida Coastal Office<br />

3900 Commonwealth Blvd., MS #235,<br />

Tallahassee, FL 32399 • www.aquaticpreserves.org

This publication funded in part through<br />

a grant agreement from the Florida<br />

Department of Environmental Protection,<br />

Florida Coastal Management Program by<br />

a grant provided by the Office of Ocean<br />

and Coastal Resource Management<br />

under the Coastal Zone Management Act<br />

of 1972, as amended, National Oceanic<br />

and Atmospheric Administration Award<br />

No. NA12NOS4190093-CM327 and<br />

NA15NOS4190096-CM06M. The views,<br />

statements, finding, conclusions, and<br />

recommendations expressed herein<br />

are those of the author(s) and do not<br />

necessarily reflect the views of the <strong>St</strong>ate of<br />

Florida, National Oceanic and Atmospheric<br />

Administration, or any of its sub-agencies.<br />

December 2016<br />

Right: Nurse shark swimming through a<br />

seagrass meadow off the <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> Keys.<br />

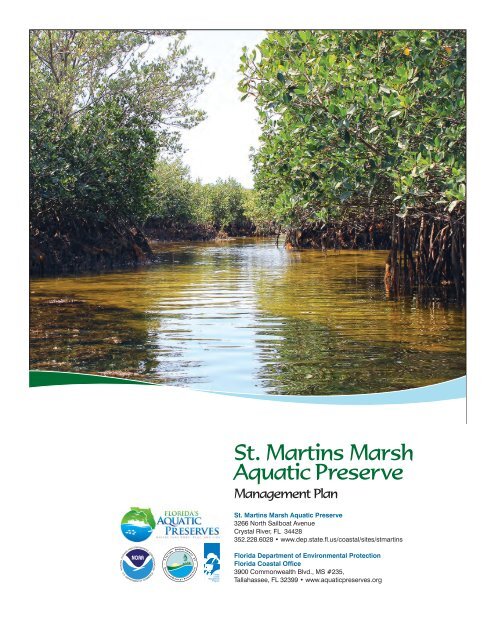

Cover photo: Tidal creek winding<br />

through red mangroves at low tide.<br />

<strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong><br />

<strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong><br />

Management Plan<br />

<strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong><br />

3266 North Sailboat Avenue<br />

Crystal River, FL 34428<br />

352.228.6028 • www.dep.state.fl.us/coastal/sites/stmartins<br />

Florida Department of Environmental Protection<br />

Florida Coastal Office<br />

3900 Commonwealth Blvd., MS #235,<br />

Tallahassee, FL 32399 • www.aquaticpreserves.org

Limestone crevice in the exposed bedrock of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.<br />

Mission <strong>St</strong>atement<br />

The Florida Coastal Office’s mission statement is: Conserving and restoring Florida’s coastal and<br />

aquatic resources for the benefit of people and the environment.<br />

The four long-term goals of the Florida Coastal Office’s <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Program are to:<br />

1. protect and enhance the ecological integrity of the aquatic preserves;<br />

2. restore areas to their natural condition;<br />

3. encourage sustainable use and foster active stewardship by engaging local communities in the<br />

protection of aquatic preserves; and<br />

4. improve management effectiveness through a process based on sound science, consistent<br />

evaluation, and continual reassessment.

Acquisition and Restoration Council Management Plan Compliance Checklist<br />

Land Management Plan Compliance Checklist<br />

Required for <strong>St</strong>ate-owned conservation lands over 160 acres<br />

Item # Requirement <strong>St</strong>atute/Rule Pg#/App<br />

Section A: Acquisition Information Items<br />

1 The common name of the property. 18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

2 The land acquisition program, if any, under which the property<br />

was acquired.<br />

3 Degree of title interest held by the Board, including reservations<br />

and encumbrances such as leases.<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

4 The legal description and acreage of the property. 18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

5 A map showing the approximate location and boundaries of the property,<br />

and the location of any structures or improvements to the property.<br />

6 An assessment as to whether the property, or any portion, should be<br />

declared surplus. Provide Information regarding assessment and<br />

analysis in the plan, and provide corresponding map.<br />

7 Identification of other parcels of land within or immediately adjacent to<br />

the property that should be purchased because they are essential to<br />

management of the property. Please clearly indicate parcels on a map.<br />

8 Identification of adjacent land uses that conflict with the planned use<br />

of the property, if any.<br />

9 A statement of the purpose for which the lands were acquired, the<br />

projected use or uses as defined in 253.034 and the statutory authority<br />

for such use or uses.<br />

10 Proximity of property to other significant <strong>St</strong>ate, local or federal land<br />

or water resources.<br />

Ex. Sum.<br />

p. 1<br />

18-2.021 p. 1, 6-8<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

Ex. Sum<br />

& p. 12<br />

p. 11<br />

18-2.021 N/A<br />

18-2.021 N/A<br />

18-2.021 p. 43-45<br />

259.032(10) p. 6<br />

18-2.021 p. 41-43<br />

Section B: Use Items<br />

11 The designated single use or multiple use management for the property,<br />

including use by other managing entities.<br />

12 A description of past and existing uses, including any unauthorized<br />

uses of the property.<br />

13 A description of alternative or multiple uses of the property considered by<br />

the lessee and a statement detailing why such uses were not adopted.<br />

14 A description of the management responsibilities of each entity involved<br />

in the property’s management and how such responsibilities will<br />

be coordinated.<br />

15 Include a provision that requires that the managing agency consult with the<br />

Division of Historical Resources, Department of <strong>St</strong>ate before taking actions<br />

that may adversely affect archeological or historical resources.<br />

16 Analysis/description of other managing agencies and private land managers,<br />

if any, which could facilitate the restoration or management of the land.<br />

17 A determination of the public uses and public access that would be<br />

consistent with the purposes for which the lands were acquired.<br />

18 A finding regarding whether each planned use complies with the 1981<br />

<strong>St</strong>ate Lands Management Plan, particularly whether such uses represent<br />

“balanced public utilization,” specific agency statutory authority and<br />

any other legislative or executive directives that constrain the use<br />

of such property.<br />

19 Letter of compliance from the local government stating that the LMP is<br />

in compliance with the Local Government Comprehensive Plan.<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

p. 10<br />

18-2.018 N/A<br />

p. 9-10, 37-<br />

38, 43-45,<br />

70-71<br />

18-2.018 p. 6-8, 47-73<br />

18-2.021 App. E.2<br />

18-2.021 p. 41-43, 51-<br />

58, 61-64<br />

259.032(10) p. 69-73<br />

18-2.021 p. 6-8<br />

BOT requirement<br />

App. E.3

Land Management Plan Compliance Checklist<br />

Required for <strong>St</strong>ate-owned conservation lands over 160 acres<br />

Item # Requirement <strong>St</strong>atute/Rule Pg#/App<br />

20 An assessment of the impact of planned uses on the renewable and<br />

non-renewable resources of the property, including soil and water<br />

resources, and a detailed description of the specific actions that will<br />

be taken to protect, enhance and conserve these resources and to<br />

compensate/mitigate damage caused by such uses, including a<br />

description of how the manager plans to control and prevent soil<br />

erosion and soil or water contamination.<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

P. 12-22,<br />

47-73<br />

21 *For managed areas larger than 1,000 acres, an analysis of the<br />

multiple-use potential of the property which shall include the potential<br />

of the property to generate revenues to enhance the management of<br />

the property provided that no lease, easement, or license for such<br />

revenue-generating use shall be entered into if the granting of such<br />

lease, easement or license would adversely affect the tax exemption<br />

of the interest on any revenue bonds issued to fund the acquisition of<br />

the affected lands from gross income for federal income tax purposes,<br />

pursuant to Internal Revenue Service regulations.<br />

18-2.021 &<br />

253.036<br />

N/A<br />

22 If the lead managing agency determines that timber resource<br />

management is not in conflict with the primary management objectives<br />

of the managed area, a component or section, prepared by a qualified<br />

professional forester, that assesses the feasibility of managing timber<br />

resources pursuant to section 253.036, F.S.<br />

18-021 N/A<br />

23 A statement regarding incompatible use in reference to Ch. 253.034(10). 253.034(10) p. 71<br />

*The following taken from 253.034(10) is not a land management plan requirement; however, it should be considered<br />

when developing a land management plan: The following additional uses of conservation lands acquired pursuant to<br />

the Florida Forever program and other state-funded conservation land purchase programs shall be authorized, upon<br />

a finding by the Board of Trustees, if they meet the criteria specified in paragraphs (a)-(e): water resource development<br />

projects, water supply development projects, storm-water management projects, linear facilities and sustainable<br />

agriculture and forestry. Such additional uses are authorized where: (a) Not inconsistent with the management plan<br />

for such lands; (b) Compatible with the natural ecosystem and resource values of such lands; (c) The proposed use is<br />

appropriately located on such lands and where due consideration is given to the use of other available lands; (d) The<br />

using entity reasonably compensates the titleholder for such use based upon an appropriate measure of value; and<br />

(e) The use is consistent with the public interest.<br />

Section C: Public Involvement Items<br />

24 A statement concerning the extent of public involvement and local<br />

government participation in the development of the plan, if any.<br />

25 The management prospectus required pursuant to paragraph<br />

(9)(d) shall be available to the public for a period of 30 days prior to<br />

the public hearing.<br />

26 LMPs and LMP updates for parcels over 160 acres shall be developed<br />

with input from an advisory group who must conduct at least one public<br />

hearing within the county in which the parcel or project is located. Include<br />

the advisory group members and their affiliations, as well as the<br />

date and location of the advisory group meeting.<br />

27 Summary of comments and concerns expressed by the advisory group<br />

for parcels over 160 acres<br />

18-2.021 App. C<br />

259.032(10) N/A<br />

259.032(10) App. C<br />

18-2.021 App. C<br />

28 During plan development, at least one public hearing shall be held in<br />

each affected county. Notice of such public hearing shall be posted on<br />

the parcel or project designated for management, advertised in a paper<br />

of general circulation, and announced at a scheduled meeting of the local<br />

governing body before the actual public hearing. Include a copy of each<br />

County’s advertisements and announcements (meeting minutes will<br />

suffice to indicate an announcement) in the management plan.<br />

253.034(5) &<br />

259.032(10)<br />

App. C<br />

29 The manager shall consider the findings and recommendations of the<br />

land management review team in finalizing the required 10-year update<br />

of its management plan. Include managers replies to the teams findings<br />

and recommendations.<br />

259.036 N/A

Land Management Plan Compliance Checklist<br />

Required for <strong>St</strong>ate-owned conservation lands over 160 acres<br />

Item # Requirement <strong>St</strong>atute/Rule Pg#/App<br />

30 Summary of comments and concerns expressed by the management<br />

review team, if required by Section 259.036, F.S.<br />

18-2.021 N/A<br />

31 If manager is not in agreement with the management review team’s<br />

findings and recommendations in finalizing the required 10-year update<br />

of its management plan, the managing agency should explain why<br />

they disagree with the findings or recommendations.<br />

259.036 N/A<br />

Section D: Natural Resources<br />

32 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable renewable<br />

and non-renewable resources of the property regarding soil types. Use<br />

brief descriptions and include USDA maps when available.<br />

18-2.021 p. 16-18<br />

33 Insert FNAI based natural community maps when available. ARC consensus<br />

p. 24<br />

34 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable<br />

renewable and non-renewable resources of the property regarding<br />

outstanding native landscapes containing relatively unaltered flora,<br />

fauna and geological conditions.<br />

18-2.021 Ex Sum<br />

35 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable renewable<br />

and non-renewable resources of the property regarding unique natural<br />

features and/or resources including but not limited to virgin timber stands,<br />

scenic vistas, natural rivers and streams, coral reefs, natural springs,<br />

caverns and large sinkholes.<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

p. 23-33<br />

36 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable<br />

renewable and non-renewable resources of the property regarding<br />

beaches and dunes.<br />

18-2.021 p. 28<br />

37 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable renewable<br />

and non-renewable resources of the property regarding mineral resources,<br />

such as oil, gas and phosphate, etc.<br />

38 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable renewable<br />

and non-renewable resources of the property regarding fish and wildlife,<br />

both game and non-game, and their habitat.<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

p. 16<br />

p. 23-37,<br />

App. B.4<br />

39 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable renewable<br />

and non-renewable resources of the property regarding <strong>St</strong>ate and Federally<br />

listed endangered or threatened species and their habitat.<br />

40 The identification or resources on the property that are listed in the Natural<br />

Areas Inventory. Include letter from FNAI or consultant where appropriate.<br />

41 Specific description of how the managing agency plans to identify, locate,<br />

protect and preserve or otherwise use fragile, nonrenewable natural and<br />

cultural resources.<br />

18-2.021 p. 23-35,<br />

App. B.4<br />

18-2.021 p. 23-33<br />

259.032(10) p. 37-38, 47-<br />

73, App. E.2<br />

42 Habitat Restoration and Improvement 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

42-A.<br />

Describe management needs, problems and a desired outcome and<br />

the key management activities necessary to achieve the enhancement,<br />

protection and preservation of restored habitats and enhance the natural,<br />

historical and archeological resources and their values for which the lands<br />

were acquired.<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

p. 23-33, 37-<br />

38, 47-73<br />

42-B.<br />

Provide a detailed description of both short (2-year planning period) and<br />

long-term (10-year planning period) management goals, and a priority<br />

schedule based on the purposes for which the lands were acquired and<br />

include a timeline for completion.<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

42-C. The associated measurable objectives to achieve the goals. 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1

Land Management Plan Compliance Checklist<br />

Required for <strong>St</strong>ate-owned conservation lands over 160 acres<br />

Item # Requirement <strong>St</strong>atute/Rule Pg#/App<br />

42-D.<br />

The related activities that are to be performed to meet the land<br />

management objectives and their associated measures. Include fire<br />

management plans - they can be in plan body or an appendix.<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

42-E.<br />

A detailed expense and manpower budget in order to provide a<br />

management tool that facilitates development of performance measures,<br />

including recommendations for cost-effective methods of accomplishing<br />

those activities.<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

43 ***Quantitative data description of the land regarding an inventory of<br />

forest and other natural resources and associated acreage. See footnote.<br />

44 Sustainable Forest Management, including implementation of prescribed<br />

fire management<br />

253.034(5) Ex Sum<br />

18-2.021,<br />

253.034(5) &<br />

259.032(10)<br />

44-A.<br />

Management needs, problems and a desired outcome<br />

(see requirement for # 42-A).<br />

18-2.021,<br />

253.034(5) &<br />

259.032(10)<br />

N/A<br />

44-B.<br />

Detailed description of both short and long-term management goals<br />

(see requirement for # 42-B).<br />

18-2.021,<br />

253.034(5) &<br />

259.032(10)<br />

N/A<br />

44-C. Measurable objectives (see requirement for #42-C). 18-2.021,<br />

253.034(5) &<br />

259.032(10)<br />

44-D. Related activities (see requirement for #42-D). 18-2.021,<br />

253.034(5) &<br />

259.032(10)<br />

44-E. Budgets (see requirement for #42-E). 18-2.021,<br />

253.034(5) &<br />

259.032(10)<br />

N/A<br />

N/A<br />

N/A<br />

45 Imperiled species, habitat maintenance, enhancement, restoration<br />

or population restoration<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

45-A.<br />

Management needs, problems and a desired outcome<br />

(see requirement for # 42-A).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

p. 23-37,<br />

47-73<br />

45-B.<br />

Detailed description of both short and long-term management goals<br />

(see requirement for # 42-B).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

45-C. Measurable objectives (see requirement for #42-C). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

45-D. Related activities (see requirement for #42-D). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

45-E. Budgets (see requirement for #42-E). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

46 ***Quantitative data description of the land regarding an inventory of<br />

exotic and invasive plants and associated acreage. See footnote.<br />

253.034(5) App. B.3.4<br />

47 Place the Arthropod Control Plan in an appendix. If one does not exist,<br />

provide a statement as to what arrangement exists between the local<br />

mosquito control district and the management unit.<br />

BOT requirement<br />

via lease<br />

language<br />

App. B.4<br />

48 Exotic and invasive species maintenance and control 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

48-A.<br />

Management needs, problems and a desired outcome<br />

(see requirement for # 42-A).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

p. 35-37, 63<br />

48-B.<br />

Detailed description of both short and long-term management goals<br />

(see requirement for # 42-B).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1

Land Management Plan Compliance Checklist<br />

Required for <strong>St</strong>ate-owned conservation lands over 160 acres<br />

Item # Requirement <strong>St</strong>atute/Rule Pg#/App<br />

48-C. Measurable objectives (see requirement for #42-C). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

48-D. Related activities (see requirement for #42-D). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

48-E. Budgets (see requirement for #42-E). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

Section E: Water Resources<br />

53-A.<br />

53-B.<br />

49 A statement as to whether the property is within and/or adjacent to an<br />

aquatic preserve or a designated area of critical state concern or an area<br />

under study for such designation. If yes, provide a list of the appropriate<br />

managing agencies that have been notified of the proposed plan.<br />

50 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable renewable and<br />

non-renewable resources of the property regarding water resources,<br />

including water classification for each water body and the identification of any<br />

such water body that is designated as an Outstanding Florida Water under Rule<br />

62-302.700, F.A.C.<br />

51 Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable<br />

renewable and non-renewable resources of the property regarding<br />

swamps, marshes and other wetlands.<br />

52 ***Quantitative description of the land regarding an inventory of<br />

hydrological features and associated acreage. See footnote.<br />

18-2.018 &<br />

18-2.021<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

p. 1-4<br />

18-2.021 p. 1-4, 18-22<br />

18-2.021 p. 24-27<br />

253.034(5) Ex. Sum<br />

53 Hydrological Preservation and Restoration 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

Management needs, problems and a desired outcome<br />

(see requirement for # 42-A).<br />

Detailed description of both short and long-term management goals<br />

(see requirement for # 42-B).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

53-C. Measurable objectives (see requirement for #42-C). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

53-D. Related activities (see requirement for #42-D). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

53-E. Budgets (see requirement for #42-E). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

Section F: Historical, Archaeological and Cultural Resources<br />

54 **Location and description of known and reasonably identifiable<br />

renewable and non-renewable resources of the property regarding<br />

archeological and historical resources. Include maps of all cultural<br />

resources except Native American sites, unless such sites are major<br />

points of interest that are open to public visitation.<br />

18-2.018,<br />

18-2.021 &<br />

per DHR’s<br />

request<br />

Ex. Sum, p.<br />

37-38, App<br />

B.5<br />

57-A.<br />

57-B.<br />

55 ***Quantitative data description of the land regarding an inventory<br />

of significant land, cultural or historical features and associated acreage.<br />

56 A description of actions the agency plans to take to locate and<br />

identify unknown resources such as surveys of unknown archeological<br />

and historical resources.<br />

253.034(5) Ex. Sum, p.<br />

37-38, App<br />

B.5<br />

18-2.021 App. D.1<br />

57 Cultural and Historical Resources 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

Management needs, problems and a desired outcome (see requirement for<br />

# 42-A).<br />

Detailed description of both short and long-term management goals (see<br />

requirement for # 42-B).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1

Land Management Plan Compliance Checklist<br />

Required for <strong>St</strong>ate-owned conservation lands over 160 acres<br />

Item # Requirement <strong>St</strong>atute/Rule Pg#/App<br />

57-C. Measurable objectives (see requirement for #42-C). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

57-D. Related activities (see requirement for #42-D). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

57-E. Budgets (see requirement for #42-E). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

**While maps of Native American sites should not be included in the body of the management plan, the DSL<br />

urges each managing agency to provide such information to the Division of Historical Resources for inclusion in<br />

their proprietary database. This information should be available for access to new managers to assist them in<br />

developing, implementing and coordinating their management activities.<br />

Section G: Facilities (Infrastructure, Access, Recreation)<br />

58 ***Quantitative data description of the land regarding an inventory of infrastructure<br />

and associated acreage. See footnote.<br />

253.034(5) p. 77-78<br />

59 Capital Facilities and Infrastructure 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

59-A.<br />

Management needs, problems and a desired outcome (see requirement for<br />

# 42-A).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

p. 75-78,<br />

App. D.1<br />

59-B.<br />

Detailed description of both short and long-term management goals (see<br />

requirement for # 42-B).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

59-C. Measurable objectives (see requirement for #42-C). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

59-D. Related activities (see requirement for #42-D). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

59-E. Budgets (see requirement for #42-E). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

60 *** Quantitative data description of the land regarding an inventory of recreational<br />

facilities and associated acreage.<br />

253.034(5) p. 69-71,<br />

App. D.1<br />

61 Public Access and Recreational Opportunities 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

61-A.<br />

Management needs, problems and a desired outcome (see requirement for<br />

# 42-A).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

61-B.<br />

Detailed description of both short and long-term management goals (see<br />

requirement for # 42-B).<br />

259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

61-C. Measurable objectives (see requirement for #42-C). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

61-D. Related activities (see requirement for #42-D). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

61-E. Budgets (see requirement for #42-E). 259.032(10)<br />

& 253.034(5)<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

App. D.1<br />

Section H: Other/ Managing Agency Tools<br />

62 Place this LMP Compliance Checklist at the front of the plan. ARC and<br />

managing<br />

agency consensus<br />

Front & App.<br />

E.1<br />

63 Place the Executive Summary at the front of the LMP. Include a physical<br />

description of the land.<br />

ARC and<br />

253.034(5)<br />

Ex. Sum

Land Management Plan Compliance Checklist<br />

Required for <strong>St</strong>ate-owned conservation lands over 160 acres<br />

Item # Requirement <strong>St</strong>atute/Rule Pg#/App<br />

64 If this LMP is a 10-year update, note the accomplishments since the drafting<br />

of the last LMP set forth in an organized (categories or bullets) format.<br />

65 Key management activities necessary to achieve the desired outcomes<br />

regarding other appropriate resource management.<br />

66 Summary budget for the scheduled land management activities of the LMP<br />

including any potential fees anticipated from public or private entities for projects<br />

to offset adverse impacts to imperiled species or such habitat, which fees<br />

shall be used to restore, manage, enhance, repopulate, or acquire imperiled<br />

species habitat for lands that have or are anticipated to have imperiled species<br />

or such habitat onsite. The summary budget shall be prepared in such a<br />

manner that it facilitates computing an aggregate of land management costs<br />

for all state-managed lands using the categories described in s. 259.037(3)<br />

which are resource management, administration, support, capital improvements,<br />

recreation visitor services, law enforcement activities.<br />

67 Cost estimate for conducting other management activities which would<br />

enhance the natural resource value or public recreation value for which the<br />

lands were acquired, include recommendations for cost-effective methods<br />

in accomplishing those activities.<br />

ARC consensus<br />

App. D.3<br />

259.032(10) p. 47-73<br />

253.034(5) App. D.1<br />

259.032(10) App. D.1<br />

68 A statement of gross income generated, net income and expenses. 18-2.018 N/A<br />

*** = The referenced inventories shall be of such detail that objective measures and benchmarks can be established<br />

for each tract of land and monitored during the lifetime of the plan. All quantitative data collected shall<br />

be aggregated, standardized, collected, and presented in an electronic format to allow for uniform management<br />

reporting and analysis. The information collected by the DEP pursuant to s. 253.0325(2) shall be available to the<br />

land manager and his or her assignee.

Executive Summary<br />

<strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Management Plan<br />

Lead Agency<br />

Common Name of Property<br />

Location<br />

Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s (DEP) Florida Coastal Office (FCO)<br />

<strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> (SMMAP)<br />

Citrus County, Florida<br />

Acreage Total: 28,461<br />

Acreage Breakdown According to Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI) Natural Community Type<br />

FNAI Natural Communities<br />

Acreage according to GIS<br />

Hydric Hammock 1,518<br />

Shell Mounds<br />

Unknown<br />

Mangrove Swamp 1,607<br />

Salt <strong>Marsh</strong> 4,677<br />

Consolidated Substrate<br />

Unconsolidated Substrate<br />

Unknown<br />

Unknown<br />

Mollusk Reef 49<br />

Octocoral Bed<br />

Sponge Bed<br />

Algal Bed<br />

Unknown<br />

Unknown<br />

Unknown<br />

Seagrass Bed 17,705<br />

<strong>Aquatic</strong> Caves<br />

Total Acreage<br />

Management Agency<br />

Designation<br />

Unique Features<br />

Archaeological/<br />

Historical Sites<br />

Unknown<br />

25,961 (This number does not match the “Acreage Total” above due to GIS numbers,<br />

and unmapped communities.)<br />

DEP’s FCO<br />

<strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong><br />

SMMAP sits along a largely undeveloped stretch of land within one of the largest<br />

extents of salt marshes and seagrasses in the nation. Additionally, the seagrasses<br />

of SMMAP serve as a critical habitat for the Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus<br />

latirostris) and various sea turtle species, while also serving as important nursery<br />

grounds for several fish and invertebrate species of commercial and recreational<br />

fishing importance.<br />

The Department of <strong>St</strong>ate’s Division of Historical Resources has identified numerous<br />

archaeological sites within SMMAP. Prehistoric shell middens are the most prominent<br />

features of the area due to the abundance of food resources available in the surrounding<br />

estuary. Furthermore historical structures such as the Crystal River Old City Hall and the<br />

Yulee Sugar Mill Ruins are located adjacent to SMMAP.<br />

Management Needs<br />

Ecosystem<br />

Science<br />

Resource<br />

Management<br />

Seagrass communities are vital to the health of the estuaries in SMMAP. Maintaining<br />

a strategic long-term seagrass and water quality monitoring program will be crucial<br />

in sustaining this important economic resource for future generations.<br />

With little restoration measures currently required in SMMAP, management emphasis<br />

is placed on preventing new damage to resources that may occur with increased use<br />

and development. Focus is primarily on management of interconnected measures of<br />

water quality and seagrass bed conditions.

Education<br />

and Outreach<br />

Public Use<br />

Public Involvement:<br />

Education and Outreach programs in SMMAP are critical to the protection,<br />

conservation, and enhancement of the aquatic and coastal resources. The intent<br />

of the aquatic preserve education and outreach program is to provide and foster<br />

responsible public stewardship of aquatic preserve resources.<br />

Public Use in SMMAP is dominated by ecotourism, as well as commercial and<br />

recreational fishing. Common public use activities include boating, birding, camping,<br />

canoeing, kayaking, and snorkeling. Various eco-tour operators provide a way of<br />

experiencing SMMAP, with activities such as guided fishing and scalloping charters,<br />

guided kayak tours, and airboat tours.<br />

Public support is vital to the success of conservation programs. The goal is to foster<br />

understanding of the problems facing these fragile ecosystems and the steps needed to<br />

adequately manage these important resources. SMMAP staff held public and advisory<br />

committee meetings September 28 and 29, 2016 in Crystal River to receive input on the<br />

draft management plan. An additional public meeting will be held in Tallahassee when<br />

the Acquisition and Restoration Council reviews the management plan.<br />

FCO/Trustees Approval<br />

FCO Approval: ARC approval date: Trustees approval date:<br />

Comments:

Acronym List<br />

Abbreviation Meaning<br />

AG:BG Above-ground to below-ground<br />

CH3D Curvilinear-grid Hydrodynamic 3D (model)<br />

CNWR Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge<br />

COAST COastal ASsessment Team<br />

CRPSP Crystal River <strong>Preserve</strong> <strong>St</strong>ate Park<br />

CSO Citizen Support Organization<br />

DACS Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services<br />

DEP Florida Department of Environmental Protection<br />

DNR Florida Department of Natural Resources<br />

EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency<br />

DRP Division of Recreation and Parks<br />

F.A.C. Florida Administrative Code<br />

F.A.R. Florida Administrative Register<br />

FCO Florida Coastal Office<br />

FGS Florida Geological Survey<br />

FMRI Florida Marine Research Institute<br />

FWRI Fish and Wildlife Research Institute<br />

FNAI Florida Natural Areas Inventory<br />

FLAIR Florida Accounting Information Resource<br />

FLEET Florida Equipment Electronic Tracking<br />

F.S. Florida <strong>St</strong>atutes<br />

FTE Full-Time Equivalent<br />

FTP File Transfer Protocol<br />

FWC Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission<br />

FWRI Fish and Wildlife Research Institute<br />

FWS U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

G Global<br />

GARI Gulf Archaeology Research Institute<br />

GEMS Gulf Ecological Management Site<br />

GIS Geographic Information Systems<br />

IFAS Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences<br />

IRG Inwater Research Group<br />

NERR National Estuarine Research Reserve<br />

NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration<br />

NWS National Weather Service<br />

OFW Outstanding Florida Water<br />

S <strong>St</strong>ate<br />

SES Select Exempt Service<br />

SIMM Seagrass Integrated Mapping and Monitoring<br />

SMMAP <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong><br />

SWMP System-Wide Monitoring Program<br />

TMDL Total Maximum Daily Load<br />

Trustees Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund<br />

UF University of Florida<br />

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture<br />

USGS U.S. Geological Survey

Table of Contents<br />

Part One / Basis for Management<br />

Chapter 1 / Introduction..................................................................................................................................1<br />

1.1 / Management Plan Purpose and Scope..............................................................................................2<br />

1.2 / Public Involvement................................................................................................................................3<br />

Chapter 2 / The Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Florida Coastal Office................5<br />

2.1 / Introduction...........................................................................................................................................5<br />

2.2 / Management Authority.........................................................................................................................6<br />

2.3 / <strong>St</strong>atutory Authority.................................................................................................................................7<br />

2.4 / Administrative Rules..............................................................................................................................7<br />

Chapter 3 / The <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.................................................................................9<br />

3.1 / Historical Background..........................................................................................................................9<br />

3.2 / General Description............................................................................................................................10<br />

3.3 / Resource Description.........................................................................................................................12<br />

3.4 / Values..................................................................................................................................................38<br />

3.5 / Citizen Support Organization.............................................................................................................41<br />

3.6 / Adjacent Public Lands and Designated Resources .........................................................................41<br />

3.7 / Surrounding Land Use.......................................................................................................................43<br />

Part Two / Management Programs and Issues<br />

Chapter 4 / The <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> Management Programs and Issues...............................................47<br />

4.1 / The Ecosystem Science Management Program..............................................................................48<br />

Background of Ecosystem Science at <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.....................................48<br />

Current <strong>St</strong>atus of Ecosystem Science at <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.................................51<br />

Issue One / Water Quality...................................................................................................................58<br />

Issue Two / Management and Protection of Seagrasses...................................................................59<br />

4.2 / The Resource Management Program...............................................................................................60<br />

Background of Resource Management at <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>..............................61<br />

Current <strong>St</strong>atus of Resource Management at <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>...........................61<br />

Issue One / Water Quality (continued)...............................................................................................64<br />

Issue Two / Management and Protection of Seagrasses (continued)..............................................65<br />

Issue Three / Natural Resource Obstacles.........................................................................................65<br />

4.3 / The Education and Outreach Management Program......................................................................66<br />

Background of Education and Outreach at <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.............................66<br />

Current <strong>St</strong>atus of Education and Outreach <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.............................66<br />

Issue One / Water Quality (continued)................................................................................................68<br />

Issue Two / Management and Protection of Seagrasses (continued)..............................................68<br />

Issue Three / Natural Resource Obstacles (continued).....................................................................69<br />

4.4 / The Public Use Management Program.............................................................................................69<br />

Background of Public Use at <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>...................................................70<br />

Current <strong>St</strong>atus of Public Use at <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>................................................71<br />

Issue Four / Public Use.......................................................................................................................72<br />

Part Three / Additional Plans<br />

Chapter 5 / Administrative Plan...................................................................................................................75<br />

Chapter 6 / Facilities Plan.............................................................................................................................77<br />

List of Maps<br />

Map 1 / Florida Coastal Office system.............................................................................................................2<br />

Map 2 / <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>. ...............................................................................................11<br />

Map 3 / Geomorphology of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>................................................................13<br />

Map 4 / Marine terraces..................................................................................................................................15<br />

Map 5 / Soils of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>....................................................................................17<br />

Map 6 / Drainage basins of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.................................................................18<br />

Map 7 / Karst features of and nearby <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.................................................19

Map 8 / Spring shellfish harvesting zones of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.....................................21<br />

Map 9 / Winter shellfish harvesting zones of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.....................................22<br />

Map 10 / <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Florida Natural Areas Inventory natural communities........24<br />

Map 11 / Public conservation lands adjacent to <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>................................43<br />

Map 12 / Land use surrounding <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.........................................................44<br />

Map 13 / Project COAST nutrient monitoring locations................................................................................52<br />

Map 14 / Continuous water quality monitoring stations of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>................53<br />

Map 15 / Seagrass monitoring sites of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>...............................................56<br />

Map 16 / Kiosk locations for <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>...............................................................67<br />

Map 17 / Public access at <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>...................................................................72<br />

List of Tables<br />

Table 1 / <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Florida Natural Areas Inventory natural communities........25<br />

Table 2 / Land use surrounding <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>..........................................................45<br />

Table 3 / Continuous water quality monitoring stations................................................................................53<br />

List of Figures<br />

Figure 1 / <strong>St</strong>ate management structure...........................................................................................................8<br />

List of Appendices<br />

Appendix A / Legal Documents....................................................................................................................80<br />

A.1 / <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Resolution..............................................................................................................80<br />

A.2 / Florida <strong>St</strong>atutes...................................................................................................................................81<br />

A.3 / Florida Administrative Code...............................................................................................................81<br />

Appendix B / Resource Data........................................................................................................................82<br />

B.1 / Glossary of Terms...............................................................................................................................82<br />

B.2 / References..........................................................................................................................................83<br />

B.3 / Species Lists.......................................................................................................................................88<br />

Native Species......................................................................................................................................88<br />

Listed Species....................................................................................................................................122<br />

Invasive Non-native and/or Problem Species...................................................................................123<br />

B.4 / Arthropod Control Plan....................................................................................................................125<br />

B.5 / Archaeological and Historical Sites.................................................................................................126<br />

Appendix C / Public Involvement..............................................................................................................130<br />

C.1 / Advisory Committee.........................................................................................................................130<br />

List of Members and their Affiliations.................................................................................................130<br />

Florida Administrative Register Posting............................................................................................131<br />

Meeting Summary..............................................................................................................................132<br />

C.2 / Formal Public Meeting.....................................................................................................................138<br />

Florida Administrative Register Posting............................................................................................138<br />

Advertisement Flyer............................................................................................................................140<br />

Newspaper Advertisement.................................................................................................................141<br />

Summary of the Formal Public Meeting............................................................................................142<br />

Appendix D / Goals, Objectives, and <strong>St</strong>rategies.....................................................................................144<br />

D.1 / Current Goals, Objectives, and <strong>St</strong>rategies Table............................................................................144<br />

D.2 / Budget Summary Table....................................................................................................................148<br />

D.3 / Major Accomplishments Since the Approval of the Previous Plan................................................148<br />

D.4 / Gulf Priority Restoration Projects.....................................................................................................149<br />

Appendix E / Other Requirements.............................................................................................................155<br />

E.1 / Acquisition and Restoration Council Management Plan Compliance Checklist..........................155<br />

E.2 / Management Procedures for Archaeological and Historical Sites and Properties<br />

on <strong>St</strong>ate-Owned or Controlled Lands...............................................................................................162<br />

E.3 / Letter of Compliance with the County Comprehensive Plan.........................................................163

Red mangrove propagules taking root in the shallow waters of <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong> <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>.<br />

Part One<br />

Basis for Management<br />

Chapter One<br />

Introduction<br />

The Florida aquatic preserves are administered on behalf of the state by the Florida Department of<br />

Environmental Protection’s (DEP) Florida Coastal Office (FCO) as part of a network that includes 41<br />

aquatic preserves, 3 National Estuarine Research Reserves (NERRs), a National Marine Sanctuary, the<br />

Coral Reef Conservation Program, the Florida Coastal Management Program, the Outer Continental<br />

Shelf Program, and the Florida Oceans and Coastal Council. This provides for a system of significant<br />

protections to ensure that our most popular and ecologically important underwater ecosystems<br />

are cared for in perpetuity. Each of these special places is managed with strategies based on local<br />

resources, issues and conditions.<br />

Our expansive coastline and wealth of aquatic resources have defined Florida as a subtropical oasis,<br />

attracting millions of residents and visitors, and the businesses that serve them. Florida’s submerged<br />

lands play important roles in maintaining good water quality, hosting a diversity of wildlife and habitats<br />

(including economically and ecologically valuable nursery areas), and supporting a treasured quality of<br />

life for all. In the 1960s, it became apparent that the ecosystems that had attracted so many people to<br />

Florida could not support rapid growth without science-based resource protection and management. To<br />

this end, state legislators provided extra protection for certain exceptional aquatic areas by designating<br />

them as aquatic preserves.<br />

Title to submerged lands not conveyed to private landowners is held by the Board of Trustees of the<br />

Internal Improvement Trust Fund (the Trustees). The Governor and Cabinet, sitting as the Trustees, act<br />

as guardians for the people of the <strong>St</strong>ate of Florida (§253.03, Florida <strong>St</strong>atutes [F.S.]) and regulate the

use of these public lands. Through statute, the Trustees have the authority to adopt rules related to the<br />

management of sovereignty submerged lands (Florida <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Act of 1975, §258.36, F.S.). A<br />

higher layer of protection is afforded to aquatic preserves including areas of sovereignty lands that have<br />

been “set aside forever as aquatic preserves or sanctuaries for the benefit of future generations” due to<br />

“exceptional biological, aesthetic, and scientific value” (Florida <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Act of 1975, §258.36, F.S.).<br />

This tradition of concern and protection of these exceptional areas continues, and now includes: the<br />

Rookery Bay NERR in Southwest Florida, designated in 1978; the Apalachicola NERR in Northwest<br />

Florida, designated in 1979; and the Guana Tolomato Matanzas NERR in Northeast Florida, designated<br />

in 1999. In addition, the Florida Oceans and Coastal Council was created in 2005 to develop Florida’s<br />

ocean and coastal research priorities, and establish a statewide ocean research plan. The group also<br />

coordinates public and private ocean research for more effective coastal management. This dedication<br />

to the conservation of coastal and ocean resources is an investment in Florida’s future.<br />

1.1 / Management Plan Purpose and Scope<br />

With increasing development, recreation and economic pressures, our aquatic resources have the<br />

potential to be significantly impacted, either directly or indirectly. These potential impacts to resources<br />

can reduce the health and viability of the ecosystems that contain them, requiring active management to<br />

ensure the long-term health of the entire network. Effective management plans for the aquatic preserves<br />

Alabama<br />

Georgia<br />

Yellow River<br />

<strong>Marsh</strong><br />

Fort Pickens<br />

Rocky<br />

Bayou<br />

Lake<br />

Jackson<br />

Fort Clinch<br />

Nassau River -<br />

<strong>St</strong>. Johns<br />

River <strong>Marsh</strong>es<br />

Guana River <strong>Marsh</strong><br />

Atlantic Ocean<br />

<strong>St</strong>. Andrews<br />

Guana - Tolomato - Matanzas<br />

<strong>St</strong>.<br />

Joseph<br />

Bay<br />

Alligator<br />

Harbor<br />

Apalachicola<br />

Apalachicola<br />

Bay<br />

Big Bend<br />

Seagrasses<br />

Oklawaha<br />

River<br />

Pellicer Creek<br />

Tomoka<br />

<strong>Marsh</strong><br />

<strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong><br />

<strong>Marsh</strong><br />

Rainbow<br />

Springs<br />

Wekiva<br />

River<br />

Mosquito<br />

Lagoon<br />

Banana River<br />

Pinellas<br />

County<br />

Boca Ciega<br />

Bay<br />

Terra Ceia<br />

Cockroach<br />

Bay<br />

North Fork,<br />

<strong>St</strong>. Lucie<br />

Indian River -<br />

Malabar to<br />

Vero Beach<br />

Indian River -<br />

Vero Beach<br />

to Fort Pierce<br />

Jensen Beach<br />

to Jupiter Inlet<br />

Gulf of Mexico<br />

<strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>s<br />

<strong>St</strong>. Joseph Bay <strong>St</strong>ate Buffer <strong>Preserve</strong><br />

National Estuarine Research Reserves<br />

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary<br />

Coral Reef Conservation Program<br />

Lemon Bay<br />

Cape Haze<br />

Gasparilla Sound -<br />

Charlotte Harbor<br />

Pine<br />

Island<br />

Sound<br />

Estero Bay<br />

Matlacha<br />

Pass<br />

Rookery Bay<br />

Rookery Bay<br />

Cape Romano -<br />

Ten Thousand Islands<br />

Loxahatchee<br />

River - Lake<br />

Worth Creek<br />

Biscayne Bay -<br />

Cape Florida<br />

to Monroe<br />

County Line<br />

Biscayne Bay<br />

0 25 50 100 150<br />

Miles<br />

± September 2014<br />

Lignumvitae Key<br />

Coupon Bight<br />

<br />

Map 1 / Florida Coastal Office System

are essential to address this goal and each site’s own set of unique challenges. The purpose of these<br />

plans is to incorporate, evaluate and prioritize all relevant information about the site into a cohesive<br />

management strategy, allowing for appropriate access to the managed areas while protecting the longterm<br />

health of the ecosystems and their resources.<br />

The mandate for developing aquatic preserve management plans is outlined in Section 18-20.013 and<br />

Subsection 18-18.013(2) of the Florida Administrative Code (F.A.C.). Management plan development and<br />

review begins with the collection of resource information from historical data, research and monitoring,<br />

and includes input from individual FCO managers and staff, area stakeholders, and members of the<br />

general public. The statistical data, public comment, and cooperating agency information is then<br />

used to identify management issues and threats affecting the present and future integrity of the site,<br />

its boundaries, and adjacent areas. This information is used in the development and review of the<br />

management plan, which is examined for consistency with the statutory authority and intent of the<br />

<strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Program. Each management plan is evaluated periodically and revised as necessary<br />

to allow for strategic improvements. Intended to be used by site managers and other agencies or private<br />

groups involved with maintaining the natural integrity of these resources, the plan includes scientific<br />

information about the existing conditions of the site and the management strategies developed to<br />

respond to those conditions. This management plan serves as an update to the original <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Martins</strong><br />

<strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Management Plan adopted on September 9, 1987 (Florida Department of<br />

Natural Resources, 1987).<br />

To aid in the analysis and development of the management strategies for the site plans, four<br />

comprehensive management programs are identified. In each of these management programs, relevant<br />

information about the specific sites is described in an effort to create a comprehensive management<br />

plan. It is expected that the specific needs or issues are unique and vary at each location, but the four<br />

management programs will remain constant. These management programs are:<br />

• Ecosystem Science<br />

• Resource Management<br />

• Education and Outreach<br />

• Public Use<br />

In addition, unique local and regional issues are identified, and goals, objectives and strategies are<br />

established to address these issues. Finally, the program and facility needs required to meet these goals<br />

as identified. These components are all key elements in an effective coastal management program and<br />

for achieving the mission of the sites.<br />

1.2 / Public Involvement<br />

FCO recognizes the importance of stakeholder participation and encourages their involvement in the<br />

management plan development process. FCO is also committed to meeting the requirements of the<br />

Sunshine Law (§286.011, F.S.):<br />

• meetings of public boards or commissions must be open to the public;<br />

• reasonable notice of such meetings must be given; and<br />

• minutes of the meetings must be recorded.<br />

Several key steps are to be taken during management plan development. First, staff compose a draft<br />

plan after gathering information of current and historic uses; resource, cultural and historic sites; and<br />

other valuable information regarding the property and surrounding area. <strong>St</strong>aff then organize an advisory<br />

committee comprised of key stakeholders and conduct, in conjunction with the advisory committee,<br />

public meetings to engage the stakeholders for feedback on the draft plan and the development of the<br />

final draft of the management plan. Additional public meetings are held when the plan is reviewed by the<br />

Acquisition and Restoration Council and the Trustees for approval. For additional information about the<br />

advisory committee and the public meetings refer to Appendix C - Public Involvement.

Great blue heron utilizing the exposed karstic features at low tide.<br />

Chapter Two<br />

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s<br />

Florida Coastal Office<br />

2.1 / Introduction<br />

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) protects, conserves and manages Florida’s<br />

natural resources and enforces the state’s environmental laws. The DEP is the lead agency in state government<br />

for environmental management and stewardship and commands one of the broadest charges<br />

of all the state agencies, protecting Florida’s air, water and land. The DEP is divided into three primary areas:<br />

Regulatory Programs, Land and Recreation, and Water Policy and Ecosystem Restoration. Florida’s<br />

environmental priorities include restoring America’s Everglades; improving air quality; restoring and<br />

protecting the water quality in our springs, lakes, rivers and coastal waters; conserving environmentallysensitive<br />

lands; and providing citizens and visitors with recreational opportunities, now and in the future.<br />

The Florida Coastal Office (FCO) is the unit within the DEP that manages more than four million acres<br />

of submerged lands and select coastal uplands. This includes 41 aquatic preserves, three National<br />

Estuarine Research Reserves (NERRs), the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and the Coral Reef<br />

Conservation Program. All are managed in cooperation with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric<br />

Administration (NOAA).<br />

FCO manages sites in Florida for the conservation and protection of natural and historical resources and<br />

resource-based public use that is compatible with the conservation and protection of these lands. FCO is<br />

a strong supporter of the NERR system and its approach to coastal ecosystem management. The <strong>St</strong>ate<br />

of Florida has three designated NERR sites, each encompassing at least one aquatic preserve within

its boundaries. Rookery Bay NERR includes Rookery Bay <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> and Cape Romano - Ten<br />

Thousand Islands <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>; Apalachicola NERR includes Apalachicola Bay <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>; and<br />

Guana Tolomato Matanzas NERR includes Guana River <strong>Marsh</strong> <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> and Pellicer Creek <strong>Aquatic</strong><br />

<strong>Preserve</strong>. These aquatic preserves provide discrete areas designated for additional protection beyond that<br />

of the surrounding NERR and may afford a foundation for additional protective zoning in the future.<br />

Each of the Florida NERR managers serves as a regional manager overseeing multiple other aquatic<br />

preserves in their region. This management structure advances FCO’s ability to manage its sites as part<br />

of the larger statewide system.<br />

<br />

2.2 / Management Authority<br />

Established by law, aquatic preserves are submerged lands of exceptional beauty that are to be<br />

maintained in their natural or existing conditions. The intent was to forever set aside submerged lands<br />

with exceptional biological, aesthetic, and scientific values as sanctuaries, called aquatic preserves, for<br />

the benefit of future generations.<br />

The laws supporting aquatic preserve management are the direct result of the public’s awareness of and<br />

interest in protecting Florida’s aquatic environment. The extensive dredge and fill activities that occurred<br />

in the late 1960s spawned this widespread public concern. In 1966, the Board of Trustees of the Internal<br />

Improvement Trust Fund (Trustees) created the first aquatic preserve, Estero Bay, in Lee County.<br />

In 1967, the Florida Legislature passed the Randall Act (Chapter 67-393, Laws of Florida), which<br />

established procedures regulating previously unrestricted dredge and fill activities on state-owned<br />

submerged lands. That same year, the Legislature provided the statutory authority (§253.03, Florida<br />

<strong>St</strong>atutes [F.S.]) for the Trustees to exercise proprietary control over state-owned lands. Also in 1967,<br />

government focus on protecting Florida’s productive water bodies from degradation due to development<br />

led the Trustees to establish a moratorium on the sale of submerged lands to private interests. An<br />

Interagency Advisory Committee was created to develop strategies for the protection and management<br />

of state-owned submerged lands.<br />

In 1968, the Florida Constitution was revised to declare in Article II, Section 7, the state’s policy of<br />

conserving and protecting natural resources and areas of scenic beauty. That constitutional provision<br />

also established the authority for the Legislature to enact measures for the abatement of air and water<br />

pollution. Later that same year, the Interagency Advisory Committee issued a report recommending the<br />

establishment of 26 aquatic preserves.<br />

The Trustees acted on this recommendation in 1969 by establishing 16 aquatic preserves and adopting<br />

a resolution for a statewide system of such preserves. In 1975 the state Legislature passed the Florida<br />

<strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Act of 1975 (Act) that was enacted as Chapter 75-172, Laws of Florida, and later<br />

became Chapter 258, Part II, F.S. This Act codified the already existing aquatic preserves and established<br />

standards and criteria for activities within those aquatic preserves. Additional aquatic preserves were<br />

individually adopted at subsequent times up through 1989.<br />

In 1980, the Trustees adopted the first aquatic preserve rule, Chapter 18-18, Florida Administrative<br />

Code (F.A.C.), for the administration of the Biscayne Bay <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong>. All other aquatic preserves<br />

are administered under Chapter 18-20, F.A.C., which was originally adopted in 1981. These rules apply<br />

standards and criteria for activities in the aquatic preserves, such as dredging, filling, building docks and<br />

other structures that are stricter than those of Chapter 18-21, F.A.C., which apply to all sovereignty lands<br />

in the state.<br />

This plan is in compliance with the Conceptual <strong>St</strong>ate Lands Management Plan, adopted March 17,<br />

1981 by the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund and represents balanced<br />

public utilization, specific agency statutory authority, and other legislative or executive constraints.<br />

The Conceptual <strong>St</strong>ate Lands Management Plan also provides essential guidance concerning the<br />

management of sovereignty lands and aquatic preserves and their important resources, including unique<br />

natural features, seagrasses, endangered species, and archaeological and historical resources.<br />

Through delegation of authority from the Trustees, the DEP and FCO have proprietary authority to<br />

manage the sovereignty lands, the water column, spoil islands (which are merely deposits of sovereignty<br />

lands), and some of the natural islands and select coastal uplands to which the Trustees hold title.<br />

Enforcement of state statutes and rules relating to criminal violations and non-criminal infractions rests<br />

with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission law enforcement and local law enforcement<br />

agencies. Enforcement of administrative remedies rests with FCO, the DEP Districts and Water<br />

Management Districts.

2.3 / <strong>St</strong>atutory Authority<br />

The fundamental laws providing management authority for the aquatic preserves are contained in<br />

Chapters 258 and 253, F.S. These statutes establish the proprietary role of the Governor and Cabinet,<br />

sitting as the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund, as Trustees over all sovereignty<br />

lands. In addition, these statutes empower the Trustees to adopt and enforce rules and regulations for<br />

managing all sovereignty lands, including aquatic preserves. The Florida <strong>Aquatic</strong> <strong>Preserve</strong> Act was<br />

enacted by the Florida Legislature in 1975 and is codified in Chapter 258, F.S.<br />

The legislative intent for establishing aquatic preserves is stated in Section 258.36, F.S.: “It is the intent<br />

of the Legislature that the state-owned submerged lands in areas which have exceptional biological,<br />

aesthetic, and scientific value, as hereinafter described, be set aside forever as aquatic preserves or<br />

sanctuaries for the benefit of future generations.” This statement, along with the other applicable laws,<br />

provides a foundation for the management of aquatic preserves. Management will emphasize the<br />

preservation of natural conditions and will include lands that are specifically authorized for inclusion as<br />

part of an aquatic preserve.<br />

Management responsibilities for aquatic preserves may be fulfilled directly by the Trustees or by staff<br />

of the DEP through delegation of authority. Other governmental bodies may also participate in the<br />

management of aquatic preserves under appropriate instruments of authority issued by the Trustees.<br />

FCO staff serves as the primary managers who implement provisions of the management plans and<br />

rules applicable to the aquatic preserves. FCO does not “regulate” the lands per se; rather, that is done<br />

primarily by the DEP Districts (in addition to the Water Management Districts) which grant regulatory<br />

permits. The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services through delegated authority from<br />

the Trustees, may issue proprietary authorizations for marine aquaculture within the aquatic preserves<br />

and regulates all aquaculture activities as authorized by Chapter 597, Florida Aquaculture Policy Act, F.S.<br />

<strong>St</strong>aff evaluates proposed uses or activities in the aquatic preserve and assesses the possible impacts on<br />

the natural resources. Project reviews are primarily evaluated in accordance with the criteria in the Act,<br />

Chapter 18-20, F.A.C., and this management plan.<br />

FCO staff comments, along with comments of other agencies and the public are submitted to the<br />

appropriate permitting staff for consideration in their issuance of any delegated authorizations in aquatic<br />

preserves or in developing recommendations to be presented to the Trustees. This mechanism provides<br />

a basis for the Trustees to evaluate public interest and the merits of any project while also considering<br />

potential environmental impacts to the aquatic preserves. Any activity located on sovereignty lands<br />

requires a letter of consent, a lease, an easement, or other approval from the Trustees.<br />

Many provisions of the Florida <strong>St</strong>atutes that empower non-FCO programs within DEP or other agencies<br />

may be important to the management of FCO sites. For example, Chapter 403, F.S., authorizes rules<br />

concerning the designation of “Outstanding Florida Waters” (OFWs), a program that provides aquatic<br />

preserves with additional regulatory protection. Chapter 379, F.S., regulates saltwater fisheries, and<br />

provides enforcement authority and powers for law enforcement officers. Additionally, it provides similar<br />

powers relating to wildlife conservation and management. The sheer number of statutes that affect<br />

aquatic preserve management prevents an exhaustive list of all such laws from being provided here.<br />

2.4 / Administrative Rules<br />

Chapters 18-18, 18-20 and 18-21, F.A.C., are the three administrative rules directly applicable to the uses<br />