Mount Hood and the White River as it appeared early in the summer of 2020

Mount Hood’s glaciers may be retreating, but if anything, the melting ice and more extreme weather that climate change is bringing to the mountain have only made the streams that emerge from its glaciers that much more volatile.

Glacial streams are inherently intimidating: ice cold and rising dramatically within hours when glacial melting accelerates on hot summer days to become churning river of mud and silt. They can make for terrifying fords for Timberline Trail hikers and wreak havoc on downstream roads and streambanks. But the worst events typically come in fall or late spring, when sudden warming and heavy rain can trigger rapid snowmelt on the mountain, turning these streams into unruly torrents.

Highway 35 was buried under a sea of boulders in the November 2006 White River debris flow (ODOT)

Such was the setting in November 2006, when a warm front with heavy rains pounded the mountain, rapidly melting the first snows of autumn that added to the explosive runoff. The worst damage to infrastructure came from the raging White River and Newton Creek, two glacial streams that emerge from the southeast side of the mountain. The streams also happen to flank the Meadows ski resort, so when both streams effortlessly swept away whole sections of the Mount Hood Loop highway (OR 35), the resort suddenly found itself cut off from the rest of Oregon.

The 2006 floods washed away the bridge approaches and stacked boulders eight feet deep on top of the former White River Bridge (ODOT)

Highway worker posing with a boulder dropped by the White River on the centerline of Highway 35 during the 2006 floods (ODOT)

Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) crews quickly restored temporary access to the resort, but the damage to the highway was profound. Newton Creek had simply swept away the roadbed along an entire section of the highway, while the White River had swept away the bridge approaches on both sides of the concrete span over the stream – then proceeded to pile a collection of boulders on top of the stranded bridge, just for emphasis!

This overflow culvert at the east end of the old bridge approach was overwhelmed in the 2006 flood, as the White River spilled over the top of the highway, instead (ODOT)

Undaunted, the highway engineers at ODOT and the Federal Highway Administration turned to a recently completed 2003 study of design solutions for several flood-prone spot along the Highway 35. From these, a pair of projects totaling $20 million were proposed to finally tame the two streams – a “permanent” fix, as the study described it.

East of the White River, the 2006 floods also sent a torrent of water and debris down Newton and Clark Creeks, erasing sections of Highway 35 near Hood River Meadows (ODOT)

Once again, the plan was to go bigger. For Newton Creek, the now rebuilt highway includes a massive, 30-foot wide, rock-lined flood channel running parallel to the highway, with box culverts periodically spaced to allow floodwaters to cross under the road. For the White River, a series of option were considered, including a tunnel (!) and completely relocating the highway. But in the end, the option of simply replacing the older span with a much larger bridge was selected. The new bridge was completed in 2012.

Options considered in the 2003 study of possible Highway 35 crossings of the White River

[click here for a larger version of this table]

The preferred option for the White River also included a second span over Green Apple Creek, a small stream located just east of main crossing, and a feature that would serve as an overflow for the White River. Between the bridges, the new highway crossing is constructed on a high berm of fill, twenty feet above the expanse of sand and boulders that make up the White River floodplain, and berms also support the approaches to both bridges on either side of the floodplain.

When they were completed in 2012, six years after the floods that had swept away sections of the highway, these structures seemed gargantuan compared to the previous incarnation of the highway. Yet, looking down upon the new White River Bridge from higher up on the mountain, it is really nothing more than a speed bump for the raging monster the White River is capable of.

The White River has been moving east for several years. This view is from early summer 2020, when the upstream section of the river had already moved almost to the east canyon wall

For the past decade, the new structures seemed to be working as planned by the highway engineers. The White River continued to meander about in its wide flood channel, as it has for millennia, but it still found its way to the newer, bigger bridge opening. Until last winter, that is.

Sometime during the winter of 2020-21, the river abruptly formed another new channel along the east side of its floodplain, beginning about one mile above the new highway bridge. In recent years, the river had been gradually moving in this direction, including a smaller flood event in the fall of 2020 that spilled debris into the White River West SnoPark. Today’s radically new channel is a continuation of this eastward movement, almost to the east wall of the canyon.

This view from the fall of 2020 followed a debris flow that sent rock and gravel into the White River West SnoPark and set the stage for the big shift in the river’s course that would follow over the coming winter. The river was actively meandering across the latest flow in this view, settling on a new course

The berm in the center of this view was built after the 2006 floods to project the White River West SnoPark parking area (on the right) from future flooding (the White River floodplain is on the left). The fall 2020 debris flow managed to breach the berm, spreading rock and gravel across the southern corner of the parking area (the third car and most distant car in this photo is parked on the debris). The new (and now dry) White River Bridge is in the distance

By the spring of 2021, the White River had completely abandoned the main floodplain and now flows beyond the row of tress in the far distance

Looking downstream from the new White River Bridge in 2021, the former riverbed is now completely dry, with the river now flowing beyond the band of trees on the left

The White River Bridge is only a few years old, but now spans only a dry streambed

This decision to include a second bridge in the new design turned out to be fortuitous over the last winter, at least in the near term. This “overflow” bridge is now the main crossing of the recently relocated White River. Had ODOT opted to simply replace the culverts that once existed here, the river would have easily taken out a section of the berm that supports the highway between the two new bridges, closing the highway, once again. However, the second span is much smaller than the main span, so it is unclear whether the river will continue to cooperate with the highway engineers and stick to this unplanned route.

This view shows the new channel carved by the White River sometime during the winter of 2020-21

The White River carved a 20-foot-deep riverbed through loose floodplain material to form the new channel

The new bridge design included this secondary opening as a backup to the main bridge, though it is now the primary crossing of the relocated White River. The highway slopes downward as it moves east of here, dropping below the elevation of the White River floodplain, and thereby creating the potential for the river to migrate further east, threatening the fill section of the highway in the distance in this view

The channel shifts on the White River might seem to be sudden, but in reality, they are perpetual. The White River (along with the rest of Mount Hood’s glacial streams) bring tremendous loads of rock and silt with them. This has always been the case, with melting glaciers releasing debris caught up in the river of ice, some of it building piles of rock called moraines, and some carried off by the rivers that flow from the glaciers.

In the past few decades, the cycle of glacial erosion has been compounded by the retreat of the glaciers, themselves. All of Mount Hood’s glaciers are rapidly losing ice in the face of a warming climate, and the retreat of larger glaciers like the White River, Eliot, Sandy and Coe leaves behind bare ground once covered in ice.

When this happens, and erosion shifts from slow-moving ice to fast-running water, the amount of debris and water moving down the glacial streams grows dramatically. The following diagram (see below) explains this relationship in the context of the rapidly retreating Eliot Glacier, Mount Hood’s largest body of ice, located on the mountain’s northeast side.

[click here for a larger version of this schematic]

Glaciers plow wide, U-shaped valley as they grind away at the mountain, whereas streams cut deep, V-shaped canyons. When glaciers like the Eliot retreat, they expose their u-shaped valleys to stream erosion, and their outflow streams (in this case the Eliot Branch) immediately go to work cutting V-shaped canyons into the soft, newly exposed valley floor, resulting in much more material moving downstream in more volatile events.

In the schematic, the lower part of the Eliot Glacier is somewhat hidden to the casual eye, as it’s covered with rock and glacial till. This is true of most glaciers – the white upper extent marks where they are actively building up more ice with each winter, and the lower, typically debris-covered lower extent is where the ice is actively melting with each season, leaving behind a layer of collected debris that has been carried down in the flowing ice.

The terminus of the glacier in the schematic marks the point where the Eliot Branch flows from the glacier. As the terminus continues to retreat uphill with continued shrinking of the Eliot Glacier, more of the U-shaped glacial valley floor is exposed. At the bottom of the schematic, the floor of the valley has been exposed for long enough to allow the Eliot Branch to already have eroded a sizeable V-shaped canyon in the formerly flat valley. This rapid erosion has fed several debris flows down the Eliot Branch canyon in recent years, including one as recently as this month, abruptly closing the road to Laurance Lake.

The Eliot Branch continues to spread debris flows across its floodplain, burying trees in as much as 20 feet of rock and gravel. This section of the Eliot Branch flooded again earlier this month, closing the only road to Laurance Lake

We’ve seen plenty of examples of this activity around the mountain over the past couple of decades, too. In 2006 the mountain was especially active, with flooding and debris from the Sandy, Eliot, Newton Clark and White River glaciers doing extensive downstream damage to roads – this was the event that removed the highway at the White River and Newton Creek. Smaller events occurred in 1998, as well. In the 2006 event, the Lolo Pass Road was completely removed near Zigzag and the Middle Fork Hood River (which carries the outflow from the Eliot and Coe glaciers) destroyed bridges and roads in several spots.

Even in quieter times, the White River has moved its channel around steadily. That’s because the heavy debris load in the river eventually settles out when it reaches the floodplain, filling the active river channel. This eventually elevates the river to a point where it spills into older channels or even into other lower terrain. Because of the broad width of the White River floodplain at the base of the mountain, this phenomenon has occurred hundreds of times over the millennia, and the river will continue to make these moves indefinitely.

To underscore this point, the 2003 highway study of potential solutions for Highway 35 includes this eye-opening chart that shows just how many times the White River has flooded the highway or overtaken the bridges – nearly 20 events since the highway was first completed in 1925!

[click here for a larger version of this timeline]

Therein lies the folly of trying to force the river into a single 100-foot opening (or even a second overflow opening) on a half-mile wide floodplain. The fact that much of the floodplain is devoid of trees is a visual reminder that the river is in control here, and very active. It has a long history of spreading out and moving around that long precedes our era of roads and automobiles.

But the White River has an added twist in its volatility compared to most of the other glacial streams that flow from Mount Hood. The vast maze of sandy canyons that make up the headwaters of the White River are quite new, geologically speaking – at least as they appear today. This is because of a series of volcanic events in the 1780s known as the Old Maid eruptions covered Mount Hood’s south side with a deep blanket of new volcanic debris. The same gentle south slopes that Timberline Lodge and Government Camp sit on today didn’t exist before those eruptions, just 240 years ago.

The White River Glacier (center) flows from near the crater of Mount Hood, and rests upon soft slopes of rock and ash debris that were created by the Old Maid eruptions of the 1780s. The large rock monolith poking up from the crater (left of center) is Crater Rock, an 800-foot lava dome that formed during the Old Maid eruptions

The Old Maid eruptions created other new features on the mountain – notably, 800-foot Crater Rock, a prominent monolith that was pushed up from the south edge of the crater. Meanwhile, the eruptions also generated lahars, the name given to sudden, massive mudflows that can range from ice cold to boiling, depending on the origin of the event. These flows rushed down the White River, Zigzag and Sandy River valleys, burying whole forests under debris ranging from mud and silt to boulders the size of delivery trucks.

The Old Maid eruptions take their name from Old Maid Flat, located along the Sandy River, where a new forest is still struggling to take hold on top of the volcanic debris, more than two centuries later. At the White River, trees buried by the lahars can be seen in the upper canyon, where the river has cut through the Old Maid eruption debris to reveal the former canyon floor, and trees still lying where they were knocked over (more about those buried forests toward the end of this article).

From high on the rim of the White River canyon, the endless supply of rock and ash from the Old Maid deposits is apparent – along with the impossibly tiny (by comparison) “bigger bridge” over the White River

This telephoto view of the new White River bridge from the same vantage point in the upper White River canyon reveals the structure to be a mere speed bump compared to the scale and power of the White River

For this reason, the White River has an especially unstable headwaters area compared to other glaciers on the mountain, with both glacial retreat and the unstable debris from recent lahars triggering repeated flash floods and debris flows here. That’s why the question of whether the new, bigger and bolder highway bridge over the White River will be washed out is more a question of when. It will be, and in our era of rapid climate change, the answer is probably sooner than later.

Is there a better solution? Perhaps simply acknowledging that the river is perpetually on the move, and designing the road with regular reconstruction in mind, as opposed to somehow finding a grand, permanent solution. That’s at odds with the culture of highway building in this country, as it could mean simply accepting more frequent closures and more modest bridge structures – perhaps structures that could even be moved and reused when the river changes course?

The 2003 Federal Highways study actually acknowledges this reality, even if the brawny, costly designs that were ultimately constructed in 2012 do not:

“It is imperative to remember that geological, meteorological, and hydrological processes that result in debris flows, floods, and rock fall have occurred for millions of years, and will occur for millions of years to come. They are naturally occurring phenomena that with current technology cannot be completely stopped or controlled. Thus, the best that can be hoped for is to minimize the destructive, highway– closing impacts of events at the study sites.” (FHWA Highway 35 Feasibility Study, 2003)

The White River seems to be enjoying its new channel and change of scenery…

In the meantime, the newly relocated White River an awesome sight. We’re so accustomed to bending nature to our will in this modern world that it’s refreshing to see a place where nature has no intention of being fenced in (or channeled, in this case).

Do rivers have a sense of humor or experience joy? As I looked down upon the White River sparkling and splashing down its new channel this summer, it seemed to be thoroughly enjoying the pure freedom of flowing wherever it wants to. It’s yet another reminder that “nature bats last”, and in WyEast country, the mountain – and its rivers — will always have the final word.

For us, it’s that strangely comforting reminder that we’re quite insignificant in the grand scheme of things, despite our attempts to pretend otherwise.

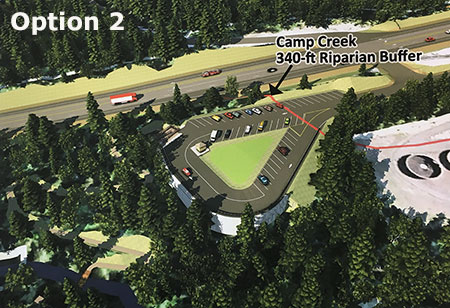

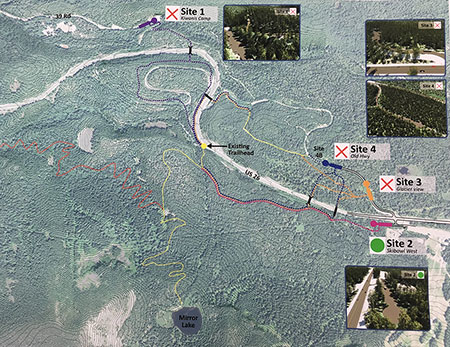

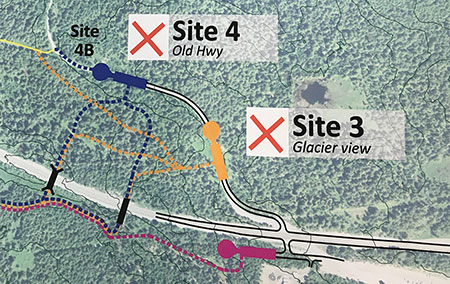

How to visit the White River

If you’re interested in experiencing the living geology of the White River, an easy introduction is to park at the White River West SnoPark area and trailhead, then head up the trail toward the mountain for a quarter mile or so. From here, the river has moved to the far side of the floodplain, but for the adventurous, it’s cross-country walk across sand and boulders to reach the stream. There, you can soak your feet in ice cold, usually milky water and watch the river moving the mountain in real time, pebble-by-pebble. The main trail is almost always within sight, so it would be tough to get lost in the open terrain here.

Look closely – those tan stripes near the bottom of the White River canyon mark the pre-Old Maid eruption slopes of Mount Hood, now buried under ash and debris from the lahars. Several preserved trees that were knocked down by the eruption can be seen along these margins. This viewpoint is along the Timberline Trail, just east of Timberline Lodge.

To see the relocated White River, park at the White River East SnoPark and walk to the east bridge – now the main crossing of the White River. The view upstream includes the top of Mount Hood, but watch out for speeding traffic when crossing the highway!

To see the buried White River forest, you can park at Timberline Lodge and follow the Timberline Trail (which is also the Pacific Crest Trail here) east for about a mile, where the trail drops to the rim of the upper White River canyon. The views here are spectacular, but if you look directly below for a waterfall on the nearest branch of the White River, you’ll also see the reddish-yellow mark of the former valley floor and the bleached remains of several ghost trees buried in the eruptions 240 years ago. Watch your step, here, and stay on the trail – the canyon rim is unstable and actively eroding!

___________________

Tom Kloster | July 2021