Berlin’s U-Bahn Expansion Plan

An obscure change in German benefit-cost analysis regulations has led to expansive proposals for urban rail construction in Germany. In Berlin, where ongoing coalition negotiations between CDU and SPD are leading in a developmentalist cars-and-trains direction, this led BVG to propose a massive program for growing the U-Bahn from its current 155 km of route-length to 318. The BVG proposal is split fairly evenly between good lines and lines that duplicate the S-Bahn and have little transportation value, and yet I’ve not seen much discussion of the individual technical merit of the program. Instead, anti-developmental activists who think they’re being pro-environment, such as BUND, regurgitate their anti-U-Bahn conspiracy theories and go to the point of associating subway tunneling with the Nazis. (I, unlike native Europeans, associate the Nazis with the Holocaust instead.)

What is the BVG proposal?

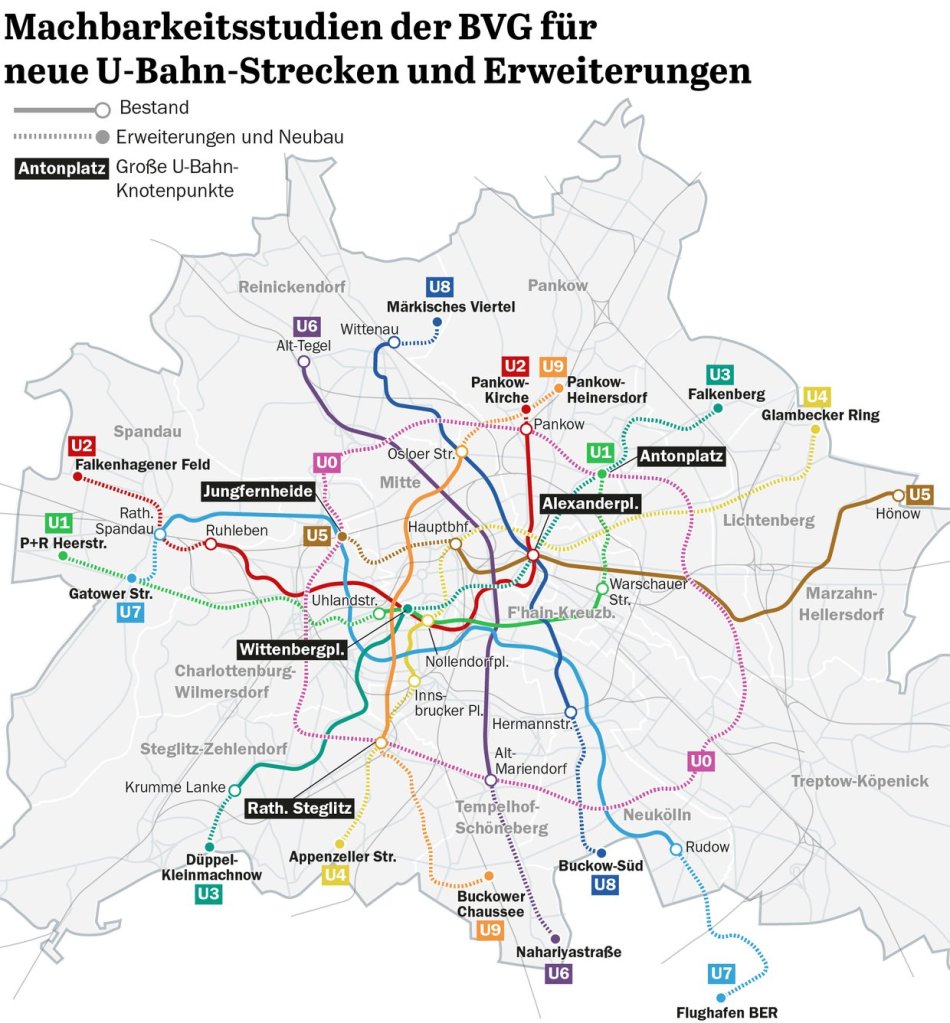

A number of media outlets have produced maps of the proposal; here is Tagesspiegel’s, reproduced here because it shows S-Bahn and regional lines as thin but visible lines.

All nine lines of the U-Bahn are to be extended, most in both directions; U3 and U4, currently a branch of U1 and a low-ridership shuttle line respectively, are to be turned into full main lines via Mitte. In addition, a ring line called U0 is to be built, duplicating the Ringbahn on its western margin and taking over some lines currently planned as radial extensions to Tegel, and running as a circumferential at consistently larger radius than the Ring to the south, east, and north.

Background

The immediate news leading BVG to propose this plan is a combination of federal and city-level changes. The federal change is obscure and I only saw it discussed by one low-follower account on Twitter, Luke Horn. Luke points out that after years of red tape, the federal government finally released its updated benefit-cost analysis regulations. As those are used to score projects, city and state governments are required to follow exact rules on which benefits may be counted, and at what rate.

One of these benefits is modal shift. It’s notoriously hard to measure, to the point that anti-U-Bahn advocates argued based on one low-count measurement that U-Bahn construction generated more emissions than it saved through modal shift; their study has just been retracted for overestimating construction emissions, but the authors are unrepentant.

At any rate, on the 21st, the new federal rules were finally published. Greenhouse gas emissions avoided through modal shift are to be counted as a benefit at the rate of 670€ per metric ton of CO2 (see PDF-p. 243). This is a high number, but it’s only high when it comes to pushing carbon taxes through a political system dominated by old climate denialists; by scientific consensus it’s more reasonable – for example, it’s close to the Stern Report estimates for the 2020s. If Germany imposed a carbon tax at this rate, and not the current rate of 55€/t, the fuel price here would grow by around 1.50€/liter, roughly doubling the price and helping kill the growing market for SUVs and luxury cars. If that is the rate at which modal shift is modeled, then even with an undercount of how urban rail construction substitutes for cars, many otherwise marginal lines pencil out.

The city-level change is that Berlin just had a redo of the 2021 election, and while technically the all-left coalition maintained its majority, CDU got the most votes, which gave Mayor Franziska Giffey (SPD) the excuse she needed to break the coalition and go into a grand coalition negotiation with CDU. Giffey had had to resign from the federal cabinet in the late Merkel era when it turned out that she had plagiarized her thesis, leading the university to revoke her degree, but out of shamelessness she remained Berlin SPD’s mayoral candidate and won in 2021. The Greens thought little of having to serve under such a scandalized mayor, and out of personal pettiness, Giffey, politically well to the right of most SPD voters anyway, accused them of personally disrespecting her and went into negotiations with CDU.

The importance of this is that the Greens (and Die Linke) are a pro-tram, anti-U-Bahn, NIMBY party. When CDU and SPD said they’d finally develop the parade of Tempelhofer Feld with housing, an advisor to a Green Bundestag member accused them of wanting to develop the area out of personal spite, and not, say, out of wanting Berlin to have more housing. Under the all-left coalition, U-Bahn planning continued but at a slow pace, and by far the most important extension on a cost per rider basis, sending U8 north to Märkisches Viertel, was deprioritized; CDU’s campaign in the election was mostly about parking and opposition to road diets, but it also hit the Greens on their opposition to U-Bahn development.

The plan as it stands has a few sops to CDU. The U0 ring is the most significant: in a country where the median age is 45, under-18s can’t vote, and CDU is disproportionately an old people’s party, CDU’s median voter was an adult through the era of the Berlin S-Bahn Boycott, as both halves of the S-Bahn were run by the East during the Cold War. Where CSU supports the Munich S-Bahn as a vehicle for conservatives to move away from the left-wing city while still having access to city jobs, Berlin CDU is uniquely more negative toward the S-Bahn. Thus, the plan has a line that mostly duplicates the Ring. The U2 expansion to the west duplicates the S-Bahn as well, especially west of Spandau. Finally, the proposed western terminus of U1 is explicitly billed as a park-and-ride, which type of service Berlin CDU has long supported.

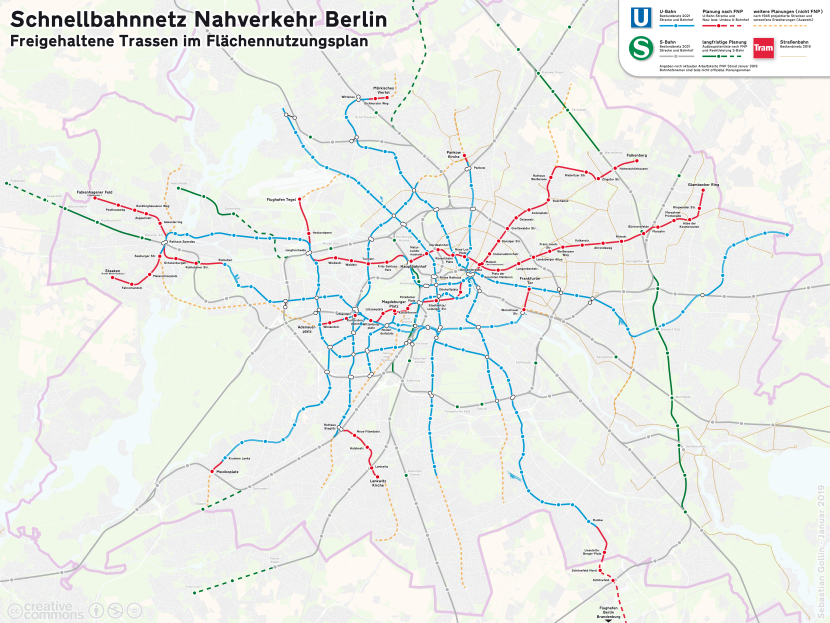

But other than the U0 ring, the plan is not too different from things that have long been planned. The longest segment other than U0 is the U3 extension to the northeast; this was part of the 200 km plan already in the 1950s, except originally the plan for this extension was not to hook into U3 as on post-Cold War plans but to run along an alignment closer to that of U9, whose southern terminus at Rathaus Steglitz was even built with room for this line, then numbered U10. A fair number of other sections on BVG’s map have a long history of languishing in unfavorable benefit-cost ratios. Other than U0, the plan is rather similar to what was studied in 2019:

However, this history has not prevented people from literally comparing BVG’s plan to the Nazis. The more prosaic reality is that the 1938 Welthauptstadt Germania U-Bahn expansion plan, other than its ring (built inside of the Ringbahn, the opposite of U0), made it to the 200 km plan and most of the lines it proposed were built, the largest change being that Cold War realities made West Berlin build U7 and U9 to serve the center of West Berlin at the Zoo rather than as additional lines serving Mitte.

The issue of costs

I have not seen an official cost estimate. BUND, which opposes the plan on the grounds that building tramways is better, says that it would cost 35 billion euros. Judging by recent construction costs of realized and proposed lines in Berlin, I think this estimate is broadly correct, if the project is run well.

The estimate is then about 210 million €/km, which looks realistic. The construction of the U5 extension from Alexanderplatz to Brandenburger Tor opened in 2020 at a cost of 280 million €/km in 2022 prices, but that was in the very center of the city, including a station at Museumsinsel mined directly beneath the Spree, for which BVG had to freeze the sandy soil. Conversely, the estimates of outer extensions that were already under planning before a week ago are lower: U7, the most advanced of these, is projected at 890 million € for about 8 km, or 110 million €/km, in an unusually easy (not really urbanized) tunneling environment.

The risk is that such a large project, done all at once, would strain the planning capacity of Berlin and Brandenburg. This exact risk happened in Paris: at 205 million €/km for 80% underground construction Grand Paris Express is more expensive per km than smaller Métro extensions built in the 2010s as it’s so large the region ran out of in-house planning capacity, and its response, setting up a British-style special purpose delivery vehicle (SPDV) along the lines of Crossrail, has resulted in British-style permanent loss of state capacity. Now, even the short Métro extensions, like the planned eastern M1 extension, cost more like GPE and not like similar projects from 10 years ago.

Notably, while France and the Nordic countries are seeing growing construction costs (France from a medium-low level and the Nordic countries from a very low one), Germany is not. I haven’t been able to find historic costs for Berlin with few exceptions. One of those exception, the last section of U9, cost 235 million € in 2022 prices for 1.5 or 1.6 km, or around 150 million €/km; this was built in 1968-74, in a relatively easy area, albeit with extra costs as noted above preparing for the U10 line. Another exception is the final section of U7 to Spandau, which cost around 800 million € for 4.9 km, or around 160 million €/km. Taken together with some numbers I posted here, it’s notable that in the 1970s, the construction costs per km in Italy, Germany, and the UK were all about the same but since then German costs have stayed the same or at worst inched up, Italian costs have fallen due to the anti-corruption laws passed in the wake of mani pulite, and British costs have quadrupled.

The most frustrating part of this discourse is that I’ve yet to see a single German rail advocate express any interest in the issue of costs. The critics of U-Bahn and other rail transport expansion plans who cite costs, of which BUND is a prime example, never talk about how to make metro construction in Germany cheaper; instead, they use it as an argument for why building underground railways is a waste of money, and urban rail must take the form of streetcars, which are held to be not only cheaper but also more moral from a green point of view as they annoy drivers. The same problem crops up in the discourse on high-speed rail, where Germany makes fairly easily fixable mistakes, generally falling under the rubric of over-accommodation of NIMBYs, and thus instead of figuring out how to build more lines, advocates write the idea off as impractical and instead talk about how to run trains on slow lines.

Can Berlin make do with streetcars?

No.

The problem with streetcars is that, no matter how much priority they get over other street traffic, they’re still slow. T3 in Paris, about the most modern urban tramway I’ve seen, running in a grassy reservation in the middle of the 40 meter wide Boulevards des Maréchaux, averages 18 km/h. The Berlin streetcars average 17.6 km/h; they don’t have 100% dedicated lanes at places, but for the most part, they too are run to very high standards, and only minor speedups can be seriously expected. Meanwhile, the U-Bahn averages 30.5 km/h, which is on the high side for the 780 m stop spacing, but is without driverless operations, which raised Paris’s average speed on M1 with its 692 m interstation from 24.4 to 30 km/h, at least in theory. The best Berlin can do with tramway modernization is probably around 20 km/h; the best it can do with the U-Bahn is probably 35 km/h, and with the S-Bahn maybe 45 km/h.

And Berlin is already large enough to need the speed. Leipzig is a good example of an Eastern city maintaining modal split with no U-Bahn, just streetcars and a recently-opened S-Bahn tunnel; in 2018, its modal split for work trips was 47% car, 20% public transport, 22% bike, 11% pedestrian (source, p. 13). But most of the walkable urban area of Leipzig is contained within a four kilometer radius of the main train station, a large majority of the city’s population is within six, and by eight one is already in the suburbs. Slow transportation like bikes and trams can work at that scale, to an extent.

In contrast with Leipzig’s smaller scale, I live four km from Berlin Hauptbahnhof and I’m still in Mitte, albeit at the neighborhood’s southeastern corner where Hbf is at the northwestern one. From the most central point, around Friedrichstrasse, both the Zoo and Warschauer Strasse are four km away, and both have high-rise office buildings. At eight km, one finally gets to Westkreuz and ICC-Messe, Steglitz, Lichtenberg, and the former airport grounds of Tegel; Gropiusstadt, a dense housing project built as transit-oriented development on top of U7, is 13 km from Friedrichstrasse by straight line.

The actual average speed, door-to-door, is always lower than the in-vehicle average speed. There’s access time, which is independent of mode, but then wait times are shorter on a high-intensity metro system than on a more diffuse streetcar network, and extra time resulting from the fact that rail lines don’t travel in a straight line from your home to your destination scales with in-vehicle travel time.

Leipzig’s modal split for work trips is 47% car, 20% public transport. Berlin’s is 28% car, 40% public transport. This is partly because Berlin is bigger, but mostly related to the city’s U-Bahn network; closer to Leipzig’s size class, one finds Prague, with a larger per capita urban rail ridership than Berlin or even Paris, with a system based on metro lines fed by streetcars and high-intensity development near the metro.

Berlin’s multiple centers make this worse. The same tram-not-subway NIMBYs who oppose U-Bahn development believe in building polycentric cities, which they moralize as more human-scale than strong city centers with tall buildings (apparently, Asia is inhuman). The problem is that when designing transportation in a polycentric city, we must always assume the worst-case scenario – that is, that an East Berliner would find work near the Zoo or even at ICC and a Spandauer would find it in Friedrichshain. The Spandauer who can only choose jobs and social destinations within streetcar distance for all intents and purposes doesn’t live in Berlin, lacking access to any citywide amenities or job opportunities; not for nothing, Spandauers don’t vote for NIMBYs, but for pro-development politicians like Raed Saleh.

Truly polycentric cities are not public transport-oriented. Upper Silesia is auto-oriented while Warsaw has one of Europe’s strongest surface rail networks. In Germany, the Rhine-Ruhr is an analog: its major cities have strong internal Stadtbahn networks, but most of the region’s population doesn’t live in Cologne or Essen or Dortmund or Dusseldorf, and the standard way to get between two randomly-selected towns there, as in Silesia, is by car.

The reason BUND and other NIMBYs don’t get this is a historical quirk of Germany. The Stadtbahn – by which I mean the subway-surface mode, not the Berlin S-Bahn line – was developed here in the 1960s and 70s, at a time of rapidly rising motorization. The goal of the systems as built in most West German cities was to decongest city center by putting the streetcars underground; then, the streetcar lines that fed into those systems were upgraded and modernized, while those that didn’t were usually closed. The urban New Left thus associates U-Bahn construction with a conspiracy to get trains out of cars’ way, and Green activists have reacted to the BVG plan by saying trams are the best specifically because they interfere with cars.

That belief is, naturally, hogwash. The subway-surface trolley, for one, was invented in turn-of-the-century Boston and Philadelphia, whose centers were so congested by streetcars, horsecars, and pedestrians that it was useful to bury some of the lines even without any cars. The metro tunnel was invented in mid-Victorian London for the same reason: the route from the train terminals on Euston Road to the City of London was so congested with horsecars there was demand for an underground route. Today, there’s less congestion than there was then, but only because the metro has been invented and the city has spread out, the latter trend raising the importance of high average speed, attainable only with full grade separation.

BUND and others say that the alternative to building 170 km of U-Bahn is building 1,700 km of streetcar. Setting aside that streetcars tend to be built in easier places and I suspect a more correct figure than 1,700 is 1,000 km, Berlin can’t really use 1,700 or 1,000 or even 500 km of tramway, because that would be too slow. Saturating every major street within the Ring with surface rail tracks would run into diminishing returns fast; the ridership isn’t there, getting it there requires high-density development that even SPD would find distasteful and not just the Greens, and streetcars with so many intersections with other streetcars would have low average speed. I can see 100-200 km of streetcar, organized in the Parisian fashion of orbital lines feeding the U- and S-Bahn; M13 on Seestrasse is a good example. But the core expansion must be U- and S-Bahn.

Okay, but is the BVG plan good?

Overall, it’s important for Berlin to expand its U- and S-Bahn networks, both by densifying them with new trunk lines and by expanding them outward. However, some of the lines on the BVG map are so out there that the plan is partly just crayon with an official imprint.

Core lines

The way I see it, the proposal includes 2.5 new trunk lines: U3 (again, formerly planned as U10), U4, and the western extension of U5.

Of those, U3 and U5 are unambiguously good. Not for nothing, they’ve been on the drawing board for generations, and many of their difficult crossings have already been built. Jungfernheide, where U5 would connect with U7, was built with such a connection in mind; the plan was and to an extent remains to extend U5 even further, sending it north to what used to be Tegel Airport and is now a planned redevelopment zone as the Urban Tech Republic, but the new BVG proposal gives away the Tegel connection to the U0 ring.

The U3 and U4 trunks in fact are planned along the routes of the two busiest tramways in the city, the M4 and combined M5/M6/M8 respectively (source, p. 7). The U3 plan thus satisfies all criteria of good subway construction – namely, it’s a direct radial line, in fact more direct than U2 (built around and not on Leipziger Strasse because the private streetcar operator objected to public U-Bahn development on its route), replacing a busy surface route. The U4 expansion mostly follows the same criterion; I am less certain about it because where M5 and M6 today serve Alexanderplatz, the proposed route goes along that of M8, which passes through the northern margin of city center, with some employment but also extensive near-center residential development near the Mitte/Gesundbrunnen boundary. I’m still positive on the idea, but I would rate it below the U3 and U5 extensions, and am also uncertain (though not negative) on the idea of connecting it from Hbf south to U4.

The U5 extension parallels no streetcar, but there’s high bus ridership along the route. The all-left coalition was planning to build a streetcar instead of an U-Bahn on this route. If it were just about connecting Jungfernheide to Hbf I’d be more understanding, but if the Urban Tech Republic project is built, then that corner of the region will need fast transportation in multiple directions, on the planning principle outlined above that in a polycentric city the public transport network must assume the worst-case scenario for where people live and work.

Outward extensions

All of Berlin’s nine U-Bahn lines are planned with at least one outward extension. These are a combination of very strong, understandable, questionable, and completely drunk.

The strongest of them all is, naturally, the U8 extension to Märkisches Viertel. In 2021, it was rated the lowest-cost-per-rider among the potential extensions in the city, at 13,160€/weekday trip; the U7 extension to the airport is projected to get 40,000 riders, making it around 22,000€/trip. It has long been to the city’s shame that it has not already completed this extension: Märkisches Viertel is dense, rather like Gropiusstadt on the opposite side of the city except with slightly less nice architecture, and needs a direct U-Bahn connection to the center.

Several other extensions are strong as well – generally ones that have been seriously planned recently. Those include U7 to the airport, the combination of the one-stop expansion of U2 to Pankow Kirche and the northeastern extension of U9 to intersect it and then terminate at the S-Bahn connection at Pankow-Heinersdorf, and U7 to the southwest to not just the depicted connection to U1 at Gatower Strasse but also along the route that the new plan gives to U1 to Heerstrasse.

The U3 expansion to the southwest is intriguing in a different way. It’s a low-cost, low-benefit extension, designed for network completeness: a one-stop extension to the S-Bahn at Mexikoplatz is being planned already, and the BVG plan acknowledges near-future S-Bahn plans adding a new southwestern branch and connect to it at Düppel.

Unfortunately, most of the other radial extensions go in the opposite direction from U3: where U3 acknowledges S-Bahn expansion and aims to connect with it, these other plans are closely parallel to S-Bahn lines that are not at capacity and are about to get even more capacity soon. Spandau, in particular, sees a train every 10 minutes; the Stadtbahn’s core segment has three trains in 10 minutes, with more demand from the east than from the west, so that a train every 10 minutes goes to Spandau, another goes to Potsdam, and a third just turns at Westkreuz since demand from the west is that weak. Creating more demand at Spandau would rebalance this system, whereas building additional U-Bahn service competing with current S-Bahn service (especially the U1 plan, which loses benefit west of the Ring) or with future expansion (such as U2 – compare with the expansion on the 2019 plan) would just waste money.

The southern extensions are a particularly bad case of not working with the S-Bahn but against it. The North-South Tunnel has 18 peak trains per hour, like the Stadtbahn; this compares with 30 on the trunk of the Munich S-Bahn. The ongoing S21 project should divert southeast, but as currently planned, it’s essentially a second North-South Tunnel, just via Hbf and not Friedrichstrasse, hence plans to beef up service to every five minutes to Wannsee and add branches, such as to Düppel. This massive increase in S-Bahn capacity is best served with more connections to the S-Bahn south of the Ring, such as east-west streetcars feeding the train; north-south U-Bahn lines, running more slowly than the S-Bahn, are of limited utility.

Finally, the extension of U1 to the northeast is a solution looking for a problem. U1’s terminus is frustratingly one S-Bahn stop away from the Ring, and perhaps the line could be extended east. But it points north, and is elevated, and past the U5 connection at Frankfurter Tor there’s no real need to serve the areas with another line to Friedrichshain.

The ring

The radial component of the BVG plan includes good and bad ideas. In contrast, the U0 ring is just a bad idea all around. The problem is that it doesn’t really hit any interesting node, except Tegel and Westkreuz, and maybe Steglitz and Pankow; Alt-Mariendorf, for example, is not especially developed. Berlin is polycentric within the Ring, but the importance of destinations outside it is usually low. This should be compared with Grand Paris Express’s M15 ring, passing through La Défense and the Stade de France.

Where circumferential service is more useful is as a feeder to S- and U-Bahn lines connecting people with the center. However, metro lines don’t make good feeders for other metro lines; this is a place where streetcars are genuinely better. The required capacity is low, since the constraints are on the radial connection to the center. The expected trip length is short and a transfer is required either way, which reduces the importance of speed – and at any rate, these outer circumferential routes are likely less congested, which further reduces the speed difference. The differences in cost permit streetcars to hit multiple stations on each line to connect with (though this means two parallel lines, not ten); this is not the same as fantasies about 1,700 km of streetcar in areas where people vote Green.

Is this a good plan?

Well, it’s about half good. Of the 163 km in BVG’s proposal, I think around 68 are good, and the rest, split between the U0 ring and the less useful outer extensions, should be shelved. That’s the crayon element – parts of the plan feel like just drawing extra extensions, by which I mean not just U0 but also the southern extensions.

However, substantial expansion of the U-Bahn is obligatory for Berlin to maintain healthy growth without being choked by cars. NIMBY fantasies about deurbanizing workplace geography would make the city more like Los Angeles than like their ideal of a 15-minute bikable small city center. Berlin needs to reject this; small is not beautiful or sustainable, and the city’s transport network needs to grow bigger and better with a lot more subway construction than is currently planned.

What’s more, the fact that construction costs in Germany are fundamentally the same in real terms as they were 40-50 years ago means that the country should accelerate its infrastructure construction program. Benefits for the most part scale with national GDP per capita – for example, the value of time for commuters, students, and other travelers so scale. Ignoring climate entirely, lines that were marginal in 1980 should be strong today; not ignoring climate, they are must-builds, as is high-density housing to fill all those trains and enable people to live in a desirable city with low car usage.

Speak of which, in Japan I recall there was a proposal to change B/C calculation by adding the benefit to local development to the B of B/C calculation but not much resulted.from it. Is that actually a reasonable move or should it be added?

Interesting to think of the main advantage of metros over trams as being speed, not capacity.

This would seem to put a premium on metro stations that are accessible from the surface, rather than extremely deep underground as is popular nowadays. It would also suggest building trams with stops further apart – if a metro can have stops every 1km, why not a tram?

Of course, big enough cities do need metro for capacity reasons. I imagine this includes Berlin for its core routes that have already been built. Only for the peripheral routes now being considered is demand low enough that trams could meet capacity.

Trams are still somewhat affected by traffic, of both the car and other tram variety, even in dedicated lanes. Add to that the fact that many tram routes still include some mixed traffic segments, and you get significantly lower speeds. It is pretty disappointing that even the recently built tram lines in Berlin still have a bunch of mixed traffic segments, even the extension from Hauptbahnhof to Turmstrasse that will open this year still shares lanes with cars in at least one part (Rathenower Str.)

It is an interesting idea to try to speed up the trams with wider stop spacing, perhaps this could be combined with a fully grade separated core trunk, feed by wider stop spacing trams. The proposed U4 might be a candidate for such a route, with a tunnel/el trunk between Landsberger Alle and Innsbrucker Platz. It would require rebuilding the U4 to be tram standards, but it has such a low ridership that shutting it down for a year to rebuild it would probably be doable.

A few trams have the occasional “gap” between stations where they pass thru low density areas. However, there are two reasons this isn’t done that often: 1) low floor trams with top speeds above 70-80 km/h are rare and high floor trams aren’t popular any more 2) trams being introduced usually means the end or drastic curtailment of parallel bus service. It is desirable both politically and from a ridership standpoint to not overly worsen the situation for existing bus riders by making them walk farther.

Weird non-arguments. Low-floor trams capable of top speeds of 80 km/h aren’t rare at all and subway construction usually curtails parallel bus service as well.

The capacity difference between a tram and a metro is not that big. The Glasgow Subway EMU has a capacity of 204 passengers (at 6 pers./m²), and a length of 39m. A MÁV-START Zrt. CityLink tramway has a capacity of 216 passengers (at 4 pers./m²) for a length of 37m. All numbers according to Stadler. If you assume the same people density (4 pers./m²), the subway is at 136 and the tramway 216.

The Glasgow Subway might be pretty narrow, and its trains short, but I suspect you are in the same ballpark for a given length…

Glasgow subway trains are unusually small even for 19th century British metro trains, they can’t really be used as a good example here. A better comparison might be made between Rio de Janeiro metro trains and Rio de Janeiro light rail trains, which have capacities of 1800 and 420 passengers respectively (though I couldn’t find the assumed crowd density), with the metro trains being about double the length of the light rail trains.

*Triple the length, I messed up the calculation there

Are there any trains (publicly accessible, actual non-toy transit) with a smaller structure gauge than the Glasgow Subway? I’ve been joking for years that the SF Bay Area tech companies should build a “minimum viable metro” aimed mostly at getting their employees to/from Caltrain, but also open to the public. To my mind, the smaller the rolling stock, the better for this scenario.

Costs are not especially sensitive to train width.

The French like their light, automated vehicles (Véhicule Automatique Léger) and the Italians have a newer product of similar size, the

MiniMetro (used e. g. in Perugia to ferry commuters, tourists and busloads of tourists(!) up into the city on a hill).

Metro naturally lends itself to longer trains than trams, because 1) trams cannot be longer than a city block without their stops blocking traffic, 2) the high passenger load of long trains means a high pedestrian volume at stops, which itself is disruptive to train and road-vehicle operation, and this is mitigated by having pedestrian passageways in your grade separated metro stop.

And even for equal train length, the metro should have about double the capacity of trams, simply because it doesn’t have to go through grade crossings. (Grade crossings mean half the time you are waiting for cross traffic, so frequency is only half as high. “Half” is an approximation, because on one hand the signal cycle doesn’t have to be 50/50 and can in fact be biased towards the train, on the other hand you need some safety margin time in which neither direction can cross the intersection, as well as acceleration/deceleration penalty. And if 50% of the time the train cannot cross the intersection, the actual hit to capacity will be more than 50% due to bunching effects caused by intersections.)

The U-Bahn trains are 100 m long and are smol by global standards; the S-Bahn, at 150, is the shortest of S-Bahns I know. Trams top at 40-something, I believe.

My impression is 100m is reasonably typical for a metro system worldwide (I think all of London’s lines are around that length), though better practice in big cities is to be 200m long, as is the case in NYC.

The longest tram I know of internationally is 80m long. I think 120m is also reasonable, but longer than that, not only will you be longer than a city block in many places, but the very length of a train rattling by will start imposing significant time penalties.

The Beijing ones look to be just under 120m long as per the length on https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/北京地铁DKZ15型电动车组.

Singapore metro trains on the north south and east west lines look to be 140m long, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kawasaki_Heavy_Industries_%26_CSR_Qingdao_Sifang_C151A But the others look to be shorter.

Even the Grossprofil trains are only 2.65m wide though, and 2.65m x 100m is absolutely small by global standards, being both kinda short and kinda narrow.

Of comparably sized cities to Berlin, Hong Kong uses mostly 3.1x180m trains, Singapore mostly uses 3.2x140m trains, Fukuoka mostly uses 2.8x120m trains. And obviously Berlin’s own S-Bahn trains are bigger, and provide important rapid transit service in the city center.

London trains are 110-130m in length, though a lot of them are also narrow (and the aggressive curvature makes them effectively even more narrow). However, I’d say London is also kinda known for small trains.

When a tram does that, it’s called an interurban. In a denser area, not-building stops like that makes less sense than for a metro because building a stop costs proportionately less (in the sense of “what length of stopless track costs the same as one stop”). And unless the tram is supposed to be the fastest mode — if there’s a metro or S-Bahn/RER in the primary traffic direction — then the tram’s speed becomes less relevant, thus sacrificing coverage doesn’t make sense.

Separately, there’s an interplay with road traffic. Most trams run either next to, or in the middle of, “medium-sized” arterial roads. If it had zero stops between light-controlled intersections with the perpendicular arterials, it would beat the cars in the parallel lanes. Set the lights for the tram, and the car lobby will whine. Set the lights for the cars, and (with some luck) the tram has to wait at the red light just about as long as a passenger-exchanging stop would take, so “it’s free”. Also makes it less likely that you miss a connection to (surface) transit on the crossing arterial.

If a tram with frequent stops is too slow for a route, then there are two options: a tram with infrequent stops, or a metro with infrequent stops. Concern for costs would mean building the tram, not the metro.

If the tram is too slow, then you really should go for grade separation. There is only so fast you can get when you have to dodge people, cars and whatever else is in the city.

I don’t care how you do grade separation, but it is needed, along with more distant stops. A tram on the surface with good transfers to a grade separated fast system (with stops so distant it can’t be called a metro) may be better than a metro, but you can’t allow the tram to go more than 20 minutes – including stops – between those transfers (so nobody is more than 10 minutes from fast transit). However this plan cannot be met by tram expansion alone, it also needs the faster transit built along side it. In tiny cities (tiny by area not population) you can get by with just a tram as there is no place to go more than 20 minutes by tram, but as cities get larger you need metro systems, and then you need to add express to your metro, in the largest cities you may even need high speed rail for intra-city travel (I hope you see that is ridiculous levels of sprawl – but it is the reality of how sprawled many cities are and it is too late

to fix that)

Remember people have places to be. Riding a train/bus for the sake of riding the train/bus is for 3 years old, adults just want to get where they need to be, and transit is a means to the end. I have no use for people who want to make it impossible to get around a city fast. Such people end up pushing for cars because at least a car can get on a local highway and get around your city fast. The car lobby is strongly united on we need more highways in the city, the bottom line of induced demand is more people are getting around the city with every lane added, even if they vastly underestimate how many more lanes are needed.

Yeah, this is one benefit of shallow construction, in addition to much lower construction costs. Note that one reason the shorter U1 extension to the west, the one shown on the 2019 map, has been deprioritized is that it would have to be shallow cut-and-cover to match the profile of the existing subway there, under a major commercial avenue for rich people.

Is there an issue with a short cut and cover U1 extension that it’d be harder to extend further at a later date?

Another way in which metros have a speed advantage over trams is by going straight when the roads on the surface are narrow and curvy. I don’t think that’s very relevant in Berlin but this is a big advantage of the northern section of the planned Brussels metro line 3. You do need deep stations to go below the street network but the speed difference makes up for all of that and then some.

Could you expand on “NIMBY fantasies about deurbanizing workplace geography”? Are there dimensions I should have in mind other than utopian ideas about remote work?

Spreading out offices and non-daily-life commercial across many small towns, rather than concentrating them into a city center and having the small towns be proper suburbs.

A great example of this type of job sprawl is Los Angeles.

The expansion program is actually not all *that* ambitious if you compare it to Madrid in the 1990s… Which ironically also included a very weird ring line (in Madrid’s case in the suburbs).

What do you think a Madrid scale expansion of Berlin subway should include that this crayon map doesn’t?

If Berlin can build at Madrid’s costs, then why not? But it probably can’t.

Well… Spain built a ton of housing before the financial crisis. In 2000, it was already at 10 dwellings/1,000 people (source); in the peak bubble years, it was about 14.

So one aspect of a Spanish-style growth plan is housing growth rates that Jusos and the Berlin Neoliberal chapter would want but that mainline SPD and FDP aren’t even thinking about. Echoes of this exist in GPE, which has some lines serving undeveloped areas to be built up or industrial areas to be redeveloped.

One upshot of this is that if the expansion program is designed to shape and not serve growth, then contra Madrid it should aim for maximum network coherence, without drunk lines like MetroSur – the housing can go on a normal radial network. In that case, beyond the lines I’ve argued are good on this plan, I’d look for stuff that can be done near the S-Bahn: a rapidly growing city also has growing suburbs, and in the case of Berlin it means S-Bahn nodes in Brandenburg. If it’s at all possible to extend S-Bahn trains to the Outer Ring and create enough demand for an Outer Ring orbital running at decent frequencies, it should be done.

On the U-Bahn, interesting growth ideas may include,

– Extending U8 past Märkisches Viertel, and likewise extending the project to the unbuilt area to its immediate north

– Extending some line southwest of Spandau toward Gatow

– Extending U2 north of Pankow Kirche along one of the tram routes, perhaps even bending northwest to provide a second route to Märkisches Viertel

– Building a longer segment of U0 as a U5 extension, maybe as far as hitting U8 and S1

– Extending U8 south to Buckow as in the BVG crayon (going as far as Britz is already justified)

– Extending U6 southeast to Quarzweg, with all the single-family houses redeveloped

But even this is more a 250 km plan than a 320 km plan. At some point, expansion just hits diminishing returns; if there’s money for massive growth in rail, spend it on completing the NBS network, closing low- and medium-speed gaps like Berlin-Halle/Leipzig, Berlin-Dresden, Hanover-Dortmund, Ingolstadt-Munich, Coburg-Nuremberg, etc.

Or a faster line to Frankfurt (Oder) there’s a surprising amount of commuting in both directions between those two cities… (currently rail distance is 75 km)

Quote: “Berlin’s is 28% car, 40% public transport.”

Where does the 40% number come from? In the linked study the number is 25.9% for automobile and 26.9% for transit (page 43, Tab 5.3)

Click to access berlin_steckbrief_berlin_gesamt.pdf

Are you just looking at Berlin Mitte?

I’m looking at work trips, on p. 4. The reason I do this is that the world is split between places that report all-trip modal split (Italy, Germany, Scandinavia, NL) and places that report work trips (Anglosphere, East Asia, France) and I’m trying to maintain some semblance of comparability.

How is it even possible to reasonably and reliably define all trip modal share on a per trip basis in a consistent way, across even just the places that report it, taking into account trip chaining?

What is biking to a train station, eating breakfast, then going to work? Is that one bike+train trip? Is that one bike trip and one train trip? What is biking to a cafe for breakfast, biking to a grocery store, then biking home? Is that one bike trip or three bike trips? What about driving to a suburban main street, walking to a cafe for breakfast, walking to a grocery store, then driving home? Is that a car trip? Or two car trips and three walking trips? Or two car trips and one walk trip?

Absent some EU wide standards, which don’t exist since not all EU countries report all trip modal share, why would all trip modal share even be comparable between even just Germany and Italy? Or even one German report and one from a couple decades ago?

It would seem like the only easily consistent all trip mode share definition would be per-passenger-kilometer, not per-trip. While that does get reported, it gives a ton of weight to intercity trips, which are less relevant when discussing specific cities.

I said the same on Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/berlin/comments/123ddtg/comment/jdvt58t/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

“Today, there’s less congestion than there was then, but only because the metro has been invented and the city has spread out, the latter trend raising the importance of high average speed, attainable only with full grade separation.”

Er, the city spread out exactly because higher-average-speed-than-before transportation was built. (Phrased this way to include everything from streetcar suburbs through Metroland-equivalents to highway-oriented suburbia.) However, mostly this is good, because it makes housing more affordable by creating more land. (Ignoring the elephant in the zoning code.)

“greeNIMBY fantasies about deurbanizing workplace geography”

Actually, what is even the idea? I was under the impression the aesthetes either think commuting is like grocery shopping (i.e. go to whichever is closest) or assumed that, because it isn’t literally impossible for everyone to live close to work (probably implying that couples have their jobs close to each other, not that only one has a job), it would just naturally happen.

“Leipzig’s modal split for work trips is 47% car, 20% public transport. Berlin’s is 28% car, 40% public transport.”

Are there any good resources for a compilation on mode splits across metro areas of different countries, using the same criteria for both metro areas (say, using the OECD classifications) and for travel (say, limiting the statistics purely to commutes)? I find it’s very difficult to get a precise sense of what cities are doing very well and what cities aren’t because of the difference in jurisdictions (cities vs metro areas) examined and the types of trips examined (commutes vs all trips).

Even just within France:

Click to access Parts%20modales%20et%20partage%20de%20l%27espace%20dans%20les%20grandes%20villes%20fran%E7aises%20-%20rapport%20%28ADETEC%29.pdf

I can find mode splits for INSEE aires urbaines, but only for all types trips of trips (instead of just commutes), and the year of data collection isn’t consistent.

Wait, the INSEE modal split data I have is commute, not all-trips. I mirror a table here.

Everything about it that’s good is nothing new but is basically just directly copied over form the 1995 200-km-Plan. The new coalition could just build that. Easy. There’s no need for a new master-plan in order for them to do so. In fact, since it’s part of the FNP, building these new lines and extensions should be relatively easy as zoning is already done with these in mind.

Everything else about it is just plain bad and dumb. Very, very dumb. Like, so dumb it’s hard to believe BVG signed off on this:

– Extending U4. Just a terrible idea. U4 is build to the “Kleinprofil”, meaning trains are even narrower than your typical Berlin tram. And in the case of U4, the platforms are limited to just 90 meters. Capacity is a far cry from the “Großprofil” of U5-U9. Extending this line towards the north-east makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. It would be far easier to just build an entirely new line as the current FNP suggests.

– The extensions of U1 and U3 in and of themselves make sense and as such are also part of the 200-km-Plan. However, for some reason, BVG decided to switch branches. The original plan was to construct the segment between Wittenbergplatz and Weißensee via Alexanderplatz according to the Großprofil. The section between Wittenbergplatz and Uhlandstraße would be easily converted since it’s rather short. Parts of this line, such as station buildings at Alexanderplatz, Rotes Rathaus and Potsdamer Platz already account for this. The new plan suggests to run the new line from Weißensee all the way to Mexikoplatz, meaning both U1 and U3 will have to be Kleinprofil with narrow, low-capacity trainsets for no reason at all.

– Besides all these new U-Bahn lines, the document suggests a whole bunch of new tram lines as well. And whilst I’m very much in favor of building both modes according to their strengths, it makes very little sense to build entirely new tram and U-Bahn lines in parallel to one another, especially if the planned tram only exists to fill in a gap in the U-Bahn network.

Essentially, the way I see it, nothing about this document is good. The fact that it just ignores technical limitations of the legacy Berlin U-Bahn system and suggests some pretty stupid lines detracts from the main goal of pushing for U-Bahn expansion. Berlin should go with the 28 year old 200-km-Plan instead. It’s still much better.

How easy is it to modify the U1 stations for Grossprofil? I can see a world in which it’s easier to modify the many at-grade stations of U3 than the two underground stations of U1.

It‘s really only one station: Uhlandstraße. Kurfürstendamm was only added in back in 1961 alongside U9 and build as a Großprofil station. Since the western part of U1 is cut-and-cover it should be easy to convert this section. Even if converting the at-grade-section of U3 would turn out be easier, there‘s still the tunnel section crossing the Ringbahn at Heidelberger Platz which would need to be build from scratch. Not to mention the fact that Heidelberger Platz is a listed station, making it next to impossible to convert it to Großprofil standards.

A lot of these extensions feel like they would only make sense in the context of big urban development plans. e.g. the southern U8 extension is mostly running through low-density housing — its only saving grace is that it’s leading to the Buckower Felder housing development area.

except…that’s about 1000 homes, which is nowhere near enough to justify an ubahn line. Maybe with a much bigger development you could pull in some funding from property developers or even tax increment financing, and start to make the thing pay for itself.

Berlin might just have enough capacity to do one major development project like that on the outskirts, but there’s no way it will manage a dozen at once

I don’t think we ever do TIFs here. We use traditional funding, without Anglo gimmicks that lead to worse planning and worse service just to avoid the appearance of government spending.

Alon, you not-infrequently often use unqualified terms like “we” and “here” that not only require readers to possess and recall personal information about you, but can also require those readers to match up past posting dates with historical knowledge of your past residences and affiliations, and even then which affiliated “we” is ambiguous. (It’s all layers and layers of Shiftless International Cosmopolitism, no doubt!)

PS I don’t know what a “TIF” is in this context. I mean, I could web search and guess, but do I wish to? No, I do not.

TIF = tax increment financing. That’s when a piece of infrastructure is economically marginal, or the local government hates the idea of transparent taxes, so it’s said to be funded by fees on new development opened up by the project. At least in the case of the 7 extension in New York, those fees didn’t materialize – the city had to give tax breaks just to get developers to go there.

These things have been a more successful in the UK where Council Tax increment financing and Community Infrastructure Levy on new development were used extensively for Crossrail, the Barking riverside extension of the Overground and the Northern Line extension. Plus TFL borrowed on the basis of the extra fee revenue. Which is why Crossrail’s lateness was one of the things with COVID that broke TFL’s finances.

Alon I know you’re very skeptical of these project specific financing gimmicks as giving options for rent seeking. I’m a bit more desperate for them to work given the wider financial constraints and the NIMBYism of the UK. (context Alon and I talked about this on Twitch recently).

My perspective comes out of the Japanese experience where they have used value capture methods extensively. Land Readjustment allows coercive land pooling* where the landowners give up land of which a section is eventually is sold to make up expenses while everybody pockets the increase in land values in their existing landholdings. Of course this needs a body to provide the financing and planning. In Japan that’s either the government or the Private railway companies. Common to both is fare revenue which is used heavily to pay off debts for full new build lines like the Tsukuba Express or Saitama Kosoku. Government makes extra return through taxation (including a small development tax but mostly land and local income taxes) while the private side-businesses do so through their side-businesses.

*Because for the role of uplift this is used for stations but not for the alignments between stations which is where the labourious buyouts are necessary.

Having a position where the mayor of London (or Manchester) can fund their own projects has a lot of political benefits.

It means the big cities are funding its own stuff which is always good.

It gives the mayor in question something positive to run on for reelection.

In the north of England it makes it more believable to the electorate that the project will actually happen.

Only London has any funding powers. Manchester is much more dependent on central government financing than London. It doesn’t have any profitable services like the Tube and property values are substantially lower and the

Also their ideas for transport expansion are basically “give us all the money no oversight, I’ll pretend to want to fund it like the Tsukuba Express but nobody in my supposedly world-class city has actually read more than the Embassy section piece”. Which makes sense since they were dumb enough to expand their overrated trams network to Trafford park instead of Strangeways north of Manchester Piccadilly. And don’t get me started on how the “2nd city” can’t figure out how to build cheaper shoulder stations instead of piling onto existing city centre stations. But hey Manchester is the smartest of the parasites regions of Britain. Maybe they should come up with a development strategy that isn’t dependent on everyone I know living in penury in London forever. Or do something about the NIMBY racists in Bury or Stockport.

Do you know what assumptions they make about future auto fleet mix and/or power generation to calculate the BCR?

In the US / UK the assumption is for mostly electric vehicles (that is what legislation says it will be in UK an California) and the benefits from mode shift end up much lower. Is this reasonable? The value of a ton of carbon is also generally assumed to be much lower than 670 euros. If the German case uses a mostly ICE fleet then all in all the resulting benefits would be on the order of 100x larger in Germany than is common in UK / US.

The accounting formula also assumes avoided car trips = less cars built and I think with that in mind it’s (nearly) a wash…

While trams can be made faster to approach the speeds of a U-bahn, the problem is that during planning, it doesn’t take much NIMBY or bad planning to insist on extra stations or circuitous alignments that result in slow Tram speeds. Example: San Jose Light Rail is slower than the worst rush hour traffic.

It’s much more challenging – though not impossible – to force a slow S-Bahn/U-Bahn design. Even when it’s slow, you’re starting with such a high speed that you’re still left with relatively fast transit.

Even the Manchester metro link is pretty slow in the city centre and most of the stops are broadly reasonable. You’d probably combine market street and shudehill. But that’s it.

Bit of thread jacking here, spinning off the U-bahn vs Trams debate.

How would you evaluate choosing between two different infrastracture mixes for orbital connections for a big cities. The Parisian orbital tram network versus the East Asian heavy orbitals (Tokyo, Osaka and Beijing are good examples). Is simply a question of scale?

I ask because TFL’s new Superloop buses are doing some of this function and I’ve been chewing on what the best mix for London would be (n/b full heavy rail orbitals in NW London, trams in the southeast, DLR and tube extensions in the East End).

Trams vs heavy rail is first a question of scale. It would be hard for a tram line to replace many of the outer heavy rail orbital lines because the line actually needs the additional capacity. Second it is a question of history. If there are freight bypasses that can be used outer orbital transit, that is clearly a cheap way to add outer orbital transit.

The more interesting question would be medium/light capacity trains in entirely new and entirely dedicated right of way (e.g., Tama Monorail), vs trams. In that case, capacity doesn’t rule out trams entirely, and you don’t happen to have a perfectly good orbital transit line already there but not yet providing transit.

In that case the bigger problem isn’t so much capacity itself as much as speed, orbital lines tend to be pretty long

Most outer orbital lines don’t make it even most of the way around though, and you aren’t intended to ride the ones that do end to end.

For example, Tama Monorail is 17km long with 19 stations. That wouldn’t be out of place if put in a list alongside outer orbital tramways in Paris.

Thanks very much for this. Glad U5 extension back on the table. Re the emissions building new U-Bahn lines – this is assuming years of tunnelling, right? Is it unthinkable for some sections to be elevated, as much of U1/U3 and some of U2 already are? East of the Ring U3 could be built above the tramway it’s relieving – with rubber-tyre technology and sounds screens along the viaduct. Similarly for outer sections of U5 to Tegel (should not be U0). And a lot cheaper than long long tunnels. Agree about U0 – tramway or a London Overground solution/tram-train would be better.